Dorothea Lange “Mr. Dougherty and kid. Warm Springs, Malheur County, Oregon” October 1939

David Holmgren, for whom I have the utmost respect, is best known as one of the co-originators of the permaculture concept. Permaculture is an ecological design method for regenerative agriculture, where the principles of natural systems are employed in order to create a self-sustaining means for food production while building soil fertility.

I am increasingly involved with permaculture (teaching it in Belize this February), as it represents one of the most important paths towards building workable life-support systems in our era of limits to growth. We are rapidly running out of options as we deplete our natural capital worldwide. While we badly need to make some informed hard choices, we collectively do not, as our consumptive system has tremendous inertia. As we reach the limits that lie in our not too distant future, permaculture can be of tremendous use, for those who implement it, in mitigating the impacts and facilitating rebuilding from the bottom-up.

David Holmgren’s Future Scenarios

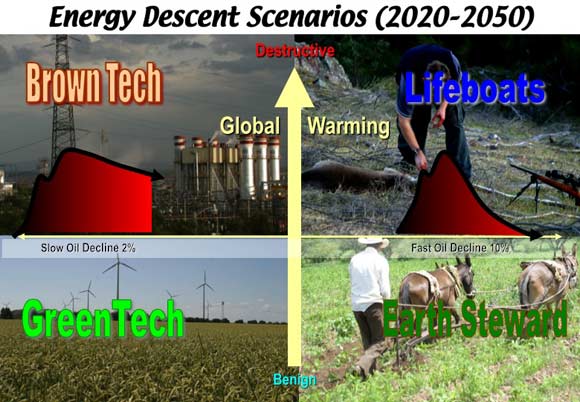

Aside from his main body of work, Holmgren has also devoted significant consideration to exploring possible future energy descent scenarios, grounded in the twin threats of peak oil and climate change. See Future Scenarios from 2009. His thought modelling looks at how these limiting factors might intertwine with sociopolitical responses to create four classes of potential outcome.

The Brown Tech scenario was seen as one of modest energy supply decline combined with rapid climate change, in a centrally controlled, corporatist context emphasizing the development of unconventional fossil fuels and nuclear power. The impact of climate disruption and other discontinuities would lead to a greater need, and support, for large-scale government intervention. This scenario summarized as top down constriction of consumption.

The Green Tech route was envisaged as gradual energy descent, gradual climate impact, and would be typified by a controlled powerdown based on a shift towards renewable energy and electrification. The minimally disruptive move towards smaller-scale, relocalized, and distributed adaptations was seen as leading to greater egalitarianism.

Earth Steward describes a situation of rapid energy supply decline leading to economic collapse and major upheaval, reducing emissions sufficiently to address climate change, but eliminating larger political power structures. A rebuild from the bottom up would be required and would allow for design principles such as permaculture to be applied.

The final scenario – Lifeboats – involves both rapid energy supply collapse and severe climate impacts. Violent collapse would result in civilizational triage in isolated locations, with small-scale attempts to preserve knowledge through a long dark age.

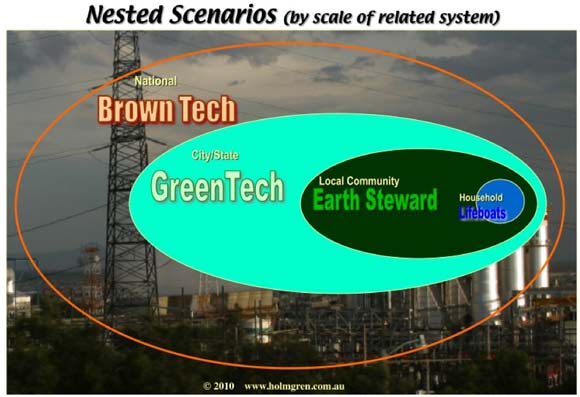

Holmgren points out that these scenarios operate at inherently different scales in terms of energy density and organizational power, with Brown Tech operating at national scale, followed by Green Tech at city state scale, Earth Steward at the level of local community and finally Lifeboat at household scale. As such they can be described as nested. This is interesting as it is analogous to the nested adaptive cycles inherent in a fractal view of human and natural systems that we have described at The Automatic Earth . Scale is indeed a critical factor, and is primarily a function of energy availability. Holmgren argues that to some extent all scenarios are emerging simultaneously, operating at their different scales.

The initial scenario work was followed up in 2010 by a new essay, Money vs Fossil Energy: The battle for control of the world, looking at the financial system, and its interactions with the energy sector, as an additional important and limiting factor in models of how the future might play out in practice. This perspective has recently been combined with an updated version of the scenario paper in Crash on Demand: Welcome to the Brown Tech Future. In this latest essay, Holmgren acknowledges he draws on our work here at The Automatic Earth, particularly in relation to projections for the global financial system and its role as a driver of global economic contraction. As such it seems appropriate to respond in order to extend the discussion.

In his recent essay, Holmgren says that he had initially been expecting a more rapid contraction in available energy, and with it a substantial fall in greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, new forms of unconventional fossil fuels have been exploited, sustaining supply for the time being, but at the cost of raising emissions, since these fuels are far more carbon intensive to produce. Holmgren understands perfectly well that unconventional fossil fuels are no answer to peak oil, given the terribly low energy profit ratio, but the temporary boost to supply has postponed the rapid contraction he, and others, had initially predicted. In addition, demand has been falling in major consuming countries as a result of the impact of financial crisis on the real economy since 2008, further easing energy supply concerns. For this reason, the Green Tech and Brown Tech scenarios, based on modest energy decline, appear more plausible to him than the Earth Steward and Lifeboat scenarios predicated upon rapid energy supply collapse. However, Green Tech would have required a major renewable energy boom sufficient to revitalize rural economies, and he recognizes that there appears to be no time for that to occur. Nor is there the collective political will to take actions to power-down or reduce emissions.

He concludes that the Brown Tech scenario appears by far the most likely, and is, in fact, already emerging. Rather than geological, biological, energetic or climate limits striking first, he suggests, in line with our view at TAE, that perturbations in the highly complex global financial system are likely to shape the future in the shorter term. As such he has become far more interested in finance, recognizing that the world has been pushed further into overshoot by throwing money at the banks, while transferring risk to the public on a massive scale, which is setting us up for a major financial reset. In combination with the climate chaos Holmgren anticipates that governments will need to assume control, moving from a market to a command economy.

Finance, Energy and Complexity

There is much I agree with here, most notably the primacy of financial collapse as a driver of short term change. The situation we find ourselves in is at such an extreme in terms of comparing the enormous overhang of virtual wealth in the form of IOUs with the actual underlying collateral that the reset could be both rapid and devastating. This could produce a number of cascading impacts on supply chains in a short space of time, as Holmgren acknowledges in citing David Korowicz’s excellent essay on the subject – Trade Off. This is likely to make governments choose to take control, but also likely to make that very difficult, and therefore very unpleasant. In some places control may win out, leading to a Brown Tech type of outcome after the dust has settled, and in others a more chaotic state may dominate, leading to more of a Lifeboat scenario. The difference may not hinge on energy supply alone, although this may well be a significant factor in some places.

It is our view at TAE that for a time energy limits are not likely to manifest, as lack of money will be the limiting factor in a major financial crisis. At the present time, with modestly increasing energy supply, the delusion of far greater increases to come, and falling demand, energy is already ceasing to be a pressing concern. As liquidity dries up, and demand falls much further as a result of both lack of purchasing power and plummeting economic activity, this will be even more the case. The perception of glut lowers prices, and this will hit the energy industry very hard due to its rapidly increasing cost base, and therefore its dependency on high prices. As prices fall and the business case disappears, much of the expensive supply will dry up, including most, if not all, of the unconventional fossil fuels currently touted as the solution.

Prices are likely to fall faster than the cost of production, leaving profit margins fatally squeezed. While money remains the limiting factor, few may worry about the energy future, but the demand collapse will lead to a supply collapse in the future due to lack of investment for a long time, the concurrent decay of existing infrastructure no one can afford to maintain, transport disruption due to a lack of letters of credit, and the impact of intentional damage inflicted by angry people. Financial crisis takes the pressure off temporarily, but a the cost of aggravating the energy shortfall, and the impact of that shortfall, in the longer term.

Producing energy from “low energy profit ratio” energy sources requires a financial system capable of providing copious amounts of affordable capital, and is dependent on the availability of cheap conventional fossil fuels in order to supply the up-front energy necessary for what are highly energy intensive processes. In energy terms, low energy profit ratio energy sources are nothing more than an extension of the current high energy profit ratio conventional fossil fuel era, which is what sustains the current level of socioeconomic complexity. The financial system is one of its most complex manifestations, and therefore one of its most vulnerable.

Once the financial system has the accident that is clearly coming, we will be looking at a substantial fall in societal complexity, but that fall in complexity will eliminate the possibility of engaging in such highly complex activities as fracking, horizontal drilling, exploiting the deep offshore or producing solar photovoltaic panels and inverters. “Low energy profit ratio” energy sources cannot by themselves maintain a level of socioeconomic complexity necessary to produce them, hence they will never be a meaningful energy source.

This is true of both unconventional fossil fuels and renewable power generation. The development of low energy profit ratio energy sources rests largely on Ponzi dynamics, and Ponzi schemes tend to come to an abrupt end.

Once this becomes clear, the gradual fall in supply is likely to morph into a rapid one. As the ability to project power at a distance depends on energy supply, and that may be compromised, perhaps within a decade, maintaining any kind of large scale command economy may not be possible for that long. However, consolidating access to a falling energy supply at the political centre under a command scenario, at the expense of the population at large, may sustain that centre for somewhat longer.

Seen through an energy profit ratio and complexity lens, a Green Tech scenario appears increasingly implausible. Green Tech – the use of technology to capture renewable energy and convert it into a concentrated form capable of doing work – is critically dependent on the fossil fuel economy to build and maintain its infrastructure, and also to maintain the level of socioeconomic complexity necessary for it, and the machinery it is meant to run, to function. A renewable energy distant future is certainly likely, but not a technological one. One can have green or tech, but ultimately not both.

Scale, Hierarchy and ‘Functional Stupidity’:

A substantial point of agreement between Holmgren’s work and ours here at TAE is that the scale Brown Tech would operate on in a constrained future would be national rather than international. There are many who worry about One World Government under a fascist model. This may have been the trajectory we have been on taken to its logical conclusion, but if crisis is indeed proximate, then we are very unlikely to reach this point. We have likened layers of political control to trophic levels in an ecosystem, as all political structures concentrate wealth at the centre at the expense of the periphery which they ‘feed upon’:

The number of levels of predation a natural system can support depends essentially on the amount of energy available at the level of primary production and the amount of energy required to harvest it. More richly endowed areas will be able to support -more- complex food webs with many levels of predation. The ocean has been able to support more levels of predation than the land, as it requires less energy to cover large distances, and primary production has been plentiful. A predator such as the tuna fish is the equivalent, in food chain terms, of a hypothetical land predator that would have eaten primarily lions. On land, ecosystems cannot support that high a level predator, as much more energy is required to harvest less plentiful energy sources.

If one thinks of political structures in similar terms, one can see that the available energy, in many forms, is a key driver of how complex and wide-ranging spheres of political control can become. Ancient imperiums achieved a great deal with energy in the forms of wood, grain and slaves from their respective peripheries. Today, we have achieved a much more all-encompassing degree of global integration thanks to the energy subsidy inherent in fossil fuels. Without this supply of energy (in fact without being able to constantly increase this supply to match population growth), the structures we have built cannot be maintained.

The international level of governance is comparable to a top level predator. When the energy supply at the base of the pyramid is reduced, and the energy required to obtain it increases, as will inevitably be the case in this era of sharply falling energy profit ratios, the system will lose the ability to support as many layers of ‘predation’. We are very likely to lose at least the top level, if not more levels on the way down as energy descent continues. A national level of Brown Tech may last for a while, but as energy descent continues, so will the diminution of the scale and complexity at which society can operate.

Living on an energy income, supplemented with limited storage in the form of grain or firewood or water stored high in the landscape, and also limited ability to physically leverage effort with slavery or the use of draft animals, does not provide the same range of possibilities as living on our energy inheritance has done. Without fossil fuels, the technology of the ancient world (Rome for instance) is probably the most that an imperial degree of energy concentration can provide. Greater concentration is possible when a wide geographical area comes under a single political hegemony and feeds a single political centre at a high level of political organization. Lower levels of political organization (ie during the inter-regnem in between successive imperiums) would provide for less resource concentration and therefore would sustain a lower level of socioeconomic complexity and ‘technology’.

Energy is not the only factor determining effective organizational scale, however. The functionality of the financial system is a major determinant of the integrity of supply chains, and hence social stability. Societal trust is vital, and can be extremely ephemeral. The more disruptive a future of limits to growth, across a range of parameters, the further downward through Holmgren’s nested scenarios we are likely to go.

In building scenarios, I would add rapid versus gradual financial crisis as a separate parameter. Personally, I believe a rapid financial crash combined with an initially slow, but then increasingly rapid fall in energy supply is the most likely scenario. Financial crisis can cause many of the effects Holmgren discusses in his scenario work in relation to energy and climate impacts.

This article addresses just one of the many issues discussed in Nicole Foss’ new video presentation, Facing the Future, co-presented with Laurence Boomert and available from the Automatic Earth Store. Get your copy now, be much better prepared for 2014, and support The Automatic Earth in the process!

As for the climate change portion of the analysis, Holmgren points out that mainstream policy is shifting from mitigation to adaptation, in recognition of the failure to achieve any kind of progress on emissions control at the international level. Substantive action to reduce emissions is seen, for obvious reasons, as precipitating economic contraction, and no government is prepared to take that risk, especially when so many are on the edge financially in any case. Holmgren also addresses the growing realizations that reductions in emissions in one region may be bought at the expense of increases in another, with no net decrease overall, and that no decoupling between resource use and economic growth is feasible.

This is very much a position I would agree with. Decoupling is nothing but an illusion. There has always been a very close correlation between energy use in particular and economic growth. In the era of globalization we claim to have reduced the energy intensity of our developed economies, but we have in fact merely displaced the energy used to the new manufacturing centres. We import goods manufactured on some other economy’s energy budget (and water budget and other resources as well). The prospects for any kind of international agreement on emissions reduction, or any kind of efficacious top-down policy response at all, seem to be bleak to non-existent.

Internationally, no one party will agree to disadvantage itself in a competitive global economy when it does not trust that others will do the same. Nationally, policies favour growth and profit. Even policies ostensibly conceived to increase energy efficiency and reduce emissions may well be implemented in a manner having the opposite effect because some aspect of that implementation was profitable for some well connected party. For instance, a policy mandating high-tech smart metering for electricity requires complex manufacturing facilities a great cost in terms of both money and energy, but can deliver only minor load shifting, leading likely to a net increase in both energy use and emissions. Low-tech metering with consumer feedback could achieve far more in terms of energy savings at far less energy cost up front, but is less profitable, and so is not implemented.

Expecting governments to deliver any improvement whatsoever in this regard appears to be quite unrealistic. Governments achieve the exact opposite of their stated policy goals with remarkable regularity, all too often making bad situations worse as expensively as possible. Dimitri Orlov quotes, and further develops, a convincing explanation for this phenomenon or large scale ‘functional stupidity’:

Mats Alvesson and André Spicer, writing in Journal of Management Studies (49:7 November 2012) present “A Stupidity-Based Theory of Organizations” in which they define a key term: functional stupidity. It is functional in that it is required in order for hierarchically structured organizations to avoid disintegration or, at the very least, to function without a great deal of internal friction. It is stupid in that it is a form of intellectual impairment: “Functional stupidity refers to an absence of reflexivity, a refusal to use intellectual capacities in other than myopic ways, and avoidance of justifications.” Alvesson and Spicer go on to define the various “…forms of stupidity management that repress or marginalize doubt and block communicative action” and to diagram the information flows which are instrumental to generating and maintaining sufficient levels of stupidity within organizations.

Hence any meaningful change will need to come from the bottom-up.

Climate

I do not focus on climate change in my own work, partly because top-down policies vary between useless and counter-productive, and partly because, in my opinion, the science is far more complex and less predictable than commonly thought, and finally because success in generating a genuine fear of climate change is likely to produce human responses that achieve far more harm than good.

Many people seem to believe there is a linear relationship between carbon dioxide as a driver and increasing temperature as the result, but if there is one thing we know about climate it is that it is not linear. The models, while complex, have not been accurate predictors of the current situation and are therefore incomplete. As for the future, the models do not include factors such as the impact of an economic collapse or a large fall in energy use. There are multiple complex feedback loops that are not well enough understood, all of which interact with each other in highly complex ways. There is also a very long term cycle of natural forcings (note the time scale in thousands of years) providing the backdrop to anthropogenic impacts, and that is also not well enough understood. The net effect of the the very long term natural cycle and the much shorter term anthropogenic impacts is unknown. Global dimming, due to particulate matter in the atmosphere, affects incident solar radiation reaching the Earth. This could change on a much faster time scale than carbon dioxide, which has a very long residence time in the atmosphere, under conditions of economic collapse. This is also not adequately modelled.

In my view the situation is too complex and chaotic to make reliable predictions. In some ways what we think we know, on the basis of assuming a system to be simpler than it actually is, can be more dangerous than what we acknowledge we do not know, as we may take entirely the wrong actions and end up compounding the problem. See for instance Allan Savory’s excellent lecture on the attempt to reverse desertification (a major source of greenhouse gas emissions) through culling fauna, finding it had the opposite effect, and now attempting to remedy the situation while haunted by regret. His talk illustrates both a very important, but mostly ignored, factor in relation to climate change, and also the dangers inherent on relying on received wisdom. Overly simplistic models are often flawed, and applying them can easily cause, or fail to avoid, substantial harm that may then be difficult to reverse.

Apocalyptic predictions of near term human extinction have been made by some commentators, and drastic ‘solutions’ proposed as a result. I would regard such predictions as unlikely, disempowering and dangerous, in the sense that they could, when fear is in the ascendancy anyway, provoke a disproportionate fear response that could in itself be very destructive. When people become collectively fearful, they tend to over-react as a crowd, potentially causing more damage through that over-reaction than might have been caused by the circumstance itself. Fear can be exploited to provide a political mandate for extremists who would then be able to wreak havoc on the fabric of society. Fear needs no encouragement at such times. It will get more than enough traction, and do more than enough damage, all by itself. Actively undermining it is a better approach, as may keep more people in a constructive headspace.

If fear of apocalyptic climate change did grab the collective imagination, there are a number of outcomes which seem particularly plausible. All of them are counter-productive in some way. The first we have already seen – carbon trading system ponzi schemes. This involves financializing yet another aspect of reality, when over-financialization, and the consequent ballooning of virtual wealth, are what have led to our current debt crisis. Financialization is popular with the powerful, because it generates substantial, and concentrable, profits, feeding greater central control by Big Capital. It would probably also generate far more greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon trading allows the wealthy to continue business as usual while paying the poor to address the problems caused, but there is no guarantee that doing so would be effective. Perverse incentives would probably see the funds used for very different purposes.

The second predictable action is massive infrastructure investment in adaptation, which could consume large amounts of finite resources and generate substantial emissions. Large scale public procurement contracts are profitable, secure sources of on-going corporate income and are highly sought-after, as we have seen in Iraq for instance. Companies able to exploit the fear could benefit very handsomely today by building things that may or may not have any value in the future. They would have an incentive to play up the fear in order to extract contracts, and this would be harmful in itself.

The third possibility is widespread geo-engineering – the deliberate release of particulate matter into the atmosphere in order to increase global dimming. This amounts to interfering in a complex and delicate system with a blunt instrument, but it fits with the prevailing technological hubris and would probably generate substantial profits for someone, hence it is all too likely to catch on. The mentality behind it is that the problems of complexity can always be addressed with greater complexity, or in other words, business as usual must continue at any price, and the consequences can always be dealt with through technological intensification. Those consequences are unpredictable and could be disastrous.

The fourth plausible response is eco-fascism, along the lines of Holmgren’s Brown Tech scenario, but with a greenwash. Times of economic contraction tend to be times when people seek control over others, and control over access to the remaining supply of resources. Any excuse will do as a pretext for establishing command and control. Eco-fascism is simply fascism at the end of the day – a mechanism for depriving the masses and consolidating, and generally abusing, tight control in the hands of the few. It would make quality of life immeasurably worse and probably not reduce carbon emissions significantly, as control mechanisms are energy intensive.

Finally, we could see a mood of collective self-flagellation take hold, with the impulse to destroy what we have built on the grounds that it is purely destructive of the natural world. Being destructive in order to remedy destructiveness seems perverse, but is already being presented as a serious imperative in some circles. If implemented it would probably lead to the general demonization of environmentalists and the full range of ideas they propose, as well as do great harm to those least able to get out of the way.

Given that these five possibilities seem the most likely responses to real fear of climate change, and that all of them are likely to make the situation worse in some way, generating fear of climate change seems to be a counter-productive strategy. We could even see several of them at once, for a truly ghastly outcome causing harm on many fronts, and at many scales, simultaneously.

Where awareness is raised without visceral fear, climate change still does not seem to be a motivator for the kind of constructive behaviours that might make a difference in the aggregate. The scale is too large for people to feel that individual actions could ever be useful, which is disempowering. The time-frame is too remote, leading to complacency, and the consequences are not perceived as personal. As humans we are not typically very good at addressing problems which are neither personal nor immediate.

The economic contraction that is coming is very likely to have a far more substantial impact on emissions than any deliberate policy or collective action. The combination of this contraction and constructive collective action could be very powerful indeed, but achieving the latter action is not best done on the grounds of climate change. The same actions that would best address climate change in the aggregate are also the prescription for dealing with financial crisis and peak oil – hold no debt, consume less, relocalize, increase community self-sufficiency, reduce dependency on centralized life-support systems.

The difference is that both financial crisis and peak oil are far more personal and immediate than climate change, and so are far bigger motivators of behavioural change. For this reason, addressing arguments in these terms is far more likely to be effective. In other words, the best way to address climate change is not to talk about it.

Grass Roots Initiatives

Holmgren argues that time is running out for bottom-up initiatives to blunt the impact of falling fossil fuel supply. While simpler ways of doing things at the household and community level could sustain a less energy dependent world, uptake is limited and time is short. Holmgren points out that during the Soviet collapse, the informal economy was the country’s saving grace, allowing people to survive the collapse of much of the larger system. For instance, when the collective farms failed, the population fed themselves on 10% of the arable land by gardening in every space to which they had access. This kind of self-reliance can be very powerful, but the ability to adapt is path-dependent. Where a society finds itself prior to collapse – in terms of physical capacity, civil society and political culture – determines how the collapse will be handled. Dale Allen Pfeiffer’s excellent book Eating Fossil Fuels, comparing the Cuban and North Korean abrupt loss of energy supplies, makes this point very clearly. Cuba, with its much better developed civil society and greater flexibility was able to adapt, albeit painfully, while the rigidly hierarchical North Korea saw very much larger impacts.

Dimitri Orlov has argued very persuasively that the Soviet Union was far better prepared than the western world to face such circumstances, as the informal economy was much better developed. The larger system was so inefficient and ineffectual that people had become accustomed to providing for themselves, and had acquired the necessary skills, both physical and organizational. Their expectations were modest in comparison with typical westerners, and their system was far less dependent on money in circulation. One would not be thrown out of a home, or have utilities cut off, for want of payment, hence people were able to withstand being paid months late if at all and were still prepared to perform the tasks which kept supply chains from collapsing.

The economic efficiency of western economies, with very little spare capacity in a system operating near its limits, is their major vulnerability. As James Howard Kunstler has put it, “efficiency is the straightest path to hell”, because there is little or no capacity to adapt in a maxed out system. The combination of little physical resilience, enormous debt, substantial vulnerability even to small a small rise in interest rates, the potential for price collapse on leveraged assets, a relatively small skill base, legal obstacles to small scale decentralized solutions, an acute dependence on money in circulation and sky high expectations in the context of widespread ignorance as to approaching limits is set to turn the collapse of the western financial system into a perfect storm.

Time is indeed short and there will be a limit to what can possibly be accomplished. However, whatever people do manage to achieve could make a difference in their local area. It is very much worth the effort, even if the task at hand appears overwhelming. Given that a top-down approach stands very little chance of altering the course of the Titanic, we might as well direct our efforts towards things that can potentially be successful as there is no better way to proceed. Reaching limits to growth will impose severe consequences, but these can be mitigated. Acting to create conditions conducive to adaptation in advance can make a difference to how crises are handled and the impact they ultimately have.

Holmgren argues that collapse in fact offers the best way forward, that a reckoning postponed will be worse when the inevitable limit is finally reached. The longer the expansion phase of the cycle continues, the greater the debt mountain and the structural dependence on cheap energy become, and the more greenhouse gas emissions are produced. Considerable pain is inflicted on the masses by the attempt to sustain the unsustainable at any cost. If we need to learn to live within limits, we should do so sooner rather than later. Holmgren focuses particularly on the potential for collapse to sharply reduce emissions, thereby perhaps preventing the climate catastrophe built into the Brown Tech scenario.

He raises the possibility that concerted effort by a large enough minority of middle class westerners to convert from dependent consumers to independent producers could derail an already over-stretched and vulnerable financial system which requires perpetual growth to survive. He suggests that a 50% reduction in consumption and a 50% conversion of assets into building resilience by 10% of the population of developed countries would create a 5% reduction in demand and savings capital available for banks to lend.

This article addresses just one of the many issues discussed in Nicole Foss’ new video presentation, Facing the Future, co-presented with Laurence Boomert and available from the Automatic Earth Store. Get your copy now, be much better prepared for 2014, and support The Automatic Earth in the process!

An involuntary demand collapse is, in any case, characteristic of periods of economic depression. Conversion of assets from the virtual wealth of the financial world to something tangible would have to be done well in advance of financial crisis, as the value of purely financial assets is likely to evaporate in a large scale repricing event, leaving nothing to convert. There are far more financial assets that constitute claims to underlying real wealth than there is real wealth to be claimed, and only the early movers will be able to make a claim. This is already well underway among the elite who are aware that financial crisis is approaching. In a world where banks create money as debt at the stroke of a pen, a pool of savings is not actually necessary for lending. Lending rests to a much greater extent on the perception of risk in the financial system. The impacts of proposed actions would not be linear, as the financial system is not mechanistic, meaning that quantitative outcomes would not necessarily be predictable. Holmgren recognizes this in his acknowledgement that small changes in the balance of supply and demand can have a disproportionate impact on prices.

Holmgren realizes the risks inherent in explicitly advocating such an approach, both at a personal level and in terms of the permaculture movement as a whole. These concerns are very valid. Permaculture has a very positive image as a solution to the need for perpetual growth, and this might be put at risk if it became associated with any deliberate attempt to cause system failure. While I understand why Holmgren would open a discussion on this front, given what is at stake, it is indeed dangerous to ‘grasp the third rail’ in this way. This approach has some aspects in common with Deep Green Resistance, which also advocates bringing down the existing system, although in their case in a more overtly destructive manner. In a command economy scenario, which seems at least temporarily likely, such explicitly stated goals become the focus, regardless of the least-worst-option rationale and the positive means by which the goals are meant to be pursued. A movement best placed to make a difference could find itself demonized and its practices uncomprehendingly banned, which would be simply tragic.

Decentralization initiatives already face opposition, but this could become significantly worse if perceived to be even more of a direct threat to the establishment. While they hold the potential to render people who disengage from the larger system very much better off, on the grounds of increased self-reliance, they also hold the potential to make targets of the early adopters who would be required to lead the charge. Much better, in my opinion, to continue the good work with the declared, and entirely defensible, goals of building greater local resilience and security of supply while preserving and regenerating the natural world. While almost any form of advance preparation for a major crisis of civilization would have the side-effect of weakening an existing system that increasingly requires total buy-in, there is a difference between side-effect and stated goal.

The global financial system is teetering on the brink of a major crisis in any case. It does not need any action taken to bring it down as it has already had easily enough rope to hang itself. Inviting blame for an inevitable outcome seems somewhat reckless given the likelihood that many will be casting about for scapegoats. Holmgren argues that, as those who warn of a crash are likely to be blamed for causing it anyway, they might as well be proactive about it. Personally, I would rather not provide a convenient justification for misplaced blame.

Holmgren discusses the case for seeking disinvestment from fossil fuel industries, citing the report Unburnable Carbon 2013: Wasted Capital and Stranded Assets. The premise of this report is that 60-80% of the fossil fuel reserves on the books of energy companies could become worthless stranded assets if governments implemented decisive action on climate change. If this perception caught on, the authors suggest it might cause investors to dump the sector rapidly, causing a proportionate loss of share value as a result. Financial markets do not work this way. Prices are not based on the fundamentals, and the prevailing positive feedback dynamics cause disproportionate reactions in both directions. Shares in fossil fuel companies will never be valued rationally in accordance with the supposedly predictable impacts of government regulation. Just as they are over-valued at times when commodities are prices peaking on fear of imminent shortages, they become undervalued in the following bust. First they are bid up beyond what the fundamentals would justify, then they crash to far below.

Personally, I regard the probability of governments acting to actually constrain emissions as negligible in any case, for reasons already discussed. Comprehensive regulatory capture has ensured that Big Capital writes the rules by which it is regulated. It is not going to impose controls which harm its own profitability. Energy is inherently valuable, and will only become more so in an energy constrained future. (However, the value of energy and the value of energy companies are not the same thing.) While low energy profit ratio energy sources are only a manifestation of the current bubble, and will eventually be abandoned out of necessity, remaining high energy profit ratio energy sources are highly unlikely to be left underground in the longer term, whatever the impact of burning them might be.

Their exploitation may well be delayed during a period of economic depression where demand would be low, financial risk would be high as price would fall faster than the cost of production, and economic visibility would be low. Very little investment occurs during contractionary times, but as the economy eventually moves into a form of limited recovery, demand would pick up and resource constraints would reassert themselves as limiting factors. At that point, anything which could be exploited almost certainly would be, and there may well be conflict over the right to exploit resources. Oil remains liquid hegemonic power and adequately accessible reserves will never become stranded assets.

In a world of short term priorities, longer term considerations are not taken into consideration, and the destabilization inherent in a period of crisis only aggravates short-termism by causing discount rates to spike. Unfortunately, environmental concerns are longer term.

Holmgren emphasizes the need to prioritize local investment in the real economy, with which I very much agree. He points out that affluent nations have a long history of extracting wealth from the informal household and community sectors for the benefit of the formal, monetized economy, but that we have little experience of reversing that trend. Michael Shuman’s excellent book Local Dollars, Local Sense makes the case for the substantial benefits that could be achievable if such a shift were to take place. Of course, as already discussed, time is short, but still, any informed action taken in advance of crisis could have disproportionately beneficial effects later on. For instance, promoting business entities with a cooperative structure can be a powerful tool for maintaining relatively local control.

One way to promote local spending is to introduce a local currency. While it may well be impossible to persuade people to spend national currency only locally if it meant paying more or limiting choices, a local currency must be spent locally as it would not be accepted elsewhere. Every monetary unit spent, and therefore circulating, locally has far more beneficial effect than one spent outside the area. External spending siphons wealth away from communities, and we have been encouraged to spend almost everything externally in recent years. Cheaper alternatives operating with economies of scale have deprived local business of a market for their goods and services, often eliminating those local options over time. This is how the centre thrives at the expense of the periphery. Reversing this trend may well require instituting a monetary system which removes the option to spend it elsewhere. This, if it can persist for long enough, should act as a driver for the provision of local goods and services.

Local currencies can run in tandem with national currencies and can act to expand the money supply in a defined area. As such they can be particularly useful to address the artificial scarcity of a liquidity crunch, where people and resources still exist, but cannot be deployed for lack of money in circulation. Local currencies can be designed to depreciate, which acts as an explicit support for the velocity of money. However, this may cause difficulties if local and national currency are convertible and the national currency does not depreciate. On the other hand, lack of convertibility could make it more difficult to confer value and full acceptability on the local currency. An alternative currency which can be used to pay local taxes will have a distinct advantage in terms of acceptability as was the case in the classic example – the depression-era Austrian town of Wörgl.

Of course a money monopoly is a very significant power, and as such is very likely to be defended, as indeed it was in depression-era Austria. This limits the prospects, and likely the duration, for alternative currencies, but they nevertheless achieve a great deal while they operate, as they currently are doing in Greece. Eventually, in a period of sufficient upheaval, a money monopoly may be impossible to sustain, then local currencies would be freer to operate. They would still be subject to distortions for political gain, money printing and ponzi dynamics over the longer term, given that they would still be operated by corruptible human beings, but at least these would exist on a smaller scale, not representing systemic risk as the flaws in the larger financial system currently do. Essentially there is no such thing as an inflation-proof, peer to peer system which would be expected to be stable over the long term, as monetary systems move in cycles of boom and bust. It is our job to navigate the waves of expansion and contraction which we cannot eliminate.

Any initiative which reduces our dependence on national currency in circulation is going to be useful in this regard, including barter networks, time-banking, tool and seed libraries, and gifting. There are already well established barter networks in some countries operating at a national scale, for instance Barter Card in New Zealand and the WIR network in Switzerland. Additional networks at a local scale could also be very useful, although more inherently limited in scope. Time-banking, libraries and gifting are more profoundly local, and act not just as means of exchange without the need for money, but also as mechanisms to build trust and community cohesiveness. This is a tremendous benefit in its own right, as a major boost for local resilience.

Holmgren points out that holding cash under one’s own control, outside of the banking system can greatly increase resilience by reducing dependency on the solvency of middle men. This is very much in accordance with our position at TAE, as cash is king in a period of deflation. People who spend in cash tend to spend less as it feels more like spending than electronic payments do. They tend therefore to be less likely to be overstretched and vulnerable to a financial collapse.

Building Parallel Systems

Holmgren stresses the urgent need to opt out of the increasingly centralized and destructive mainstream though building parallel systems prior to the advent of a Brown Tech future, which he feels could last many decades before descending further into a low-energy Lifeboat scenario. He points out that at the moment we have the luxury of keeping one foot in each camp, so that we have the opportunity to develop alternatives before we have to rely on the results. We can experiment, but with a safety net.

I am in agreement, with the exception of the timeframe for the longevity of a Brown Tech system. The scale of the coming disruption, albeit initially due to financial rather than energy crisis, is likely to be large enough to shorten the length of time the political centre can maintain the ability to project power at a distance. Learning curve time for opt-out solutions, short as it may be, could be very valuable. Unfortunately, attempting to straddle two worlds simultaneously can involve all the work of both with few of the benefits of either, hence moving over as far as possible to concentrate on the opt-out position is probably more adaptive.

As Buckminster Fuller said, “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” In other words, change comes incrementally and organically from the bottom-up, rather than by fighting to change top-down policies. Initially, pushing for grass roots change can require considerable human energy input, but once a critical mass is reached the movement can take on a life of its own very rapidly, especially if it suddenly coincides greater advantage as prevailing circumstances shift. The proactive phase is difficult, as people rarely prepare in advance for approaching change, but proactive can become reactive as the change is reached, and the earlier effort can help to shape the direction that eventual reactive response will take.

Ideas that hit the zeitgeist can become fashionable, and this imparts much greater momentum. For instance, the tiny house movement is making it a matter of pride to live in smaller and simpler dwellings, with greater emphasis on good design than physical space. More and more young people are choosing to opt out of the path taken by their peers, as that path towards debt slavery becomes ever more obviously disadvantageous. The non-passive portion of this group is looking for direction, and is prepared to find it in non-mainstream places. Providing this could amount to seeding very fertile ground.

Being beneath the notice of larger powers hoping to maintain monopolies and control can be protective. Hence working at small scale, but in many locations simultaneously, could allow systems conferring greater local independence and resilience to become established with a lower likelihood of being suppressed as a threat by the powers-that-be.

Permaculture should be a major building-block of any kind of system reboot following the operating system crash that a financial crisis represents. After all, once we navigate that period of artificial scarcity, we will have to address the real scarcity inherent in looming resource limits. We will have to deal with the fact we are far into overshoot in comparison with the carrying capacity of the Earth, even with the artificially boosted carrying capacity we have thanks to fossil fuels (where about half of the nitrogen in the food supply comes from the artificial fixation of nitrogen from fossil fuels for instance). We have been strip mining soil fertility with intensive agri-business, disrupting the critical nitrogen cycle and poisoning the soil micro-organisms critical for fertility with pesticides such as round-up. We will have to undo all of the damage, but it will take us a very long time, and in the meantime we have over 7 billion mouths to feed. Permaculture, with its emphasis on soil regeneration, is the best possible way (click for video) to do this. If we are ever to approximate, at least temporarily, an Earth Steward scenario (in the distant future, once the dust has settled), this is the path we must take.

As Holmgren says, “A permaculture way of life empowers us to take responsibility for our own welfare, provides endless opportunities for creativity and innovation, and connects us to nature and community in ways that make sense of the world around us.” Motivated by enlightened self-interest, and operating at a manageable human scale, we can apply our knowledge of natural and human systems in the real world, without being overwhelmed by the task of feeling we are personally responsible for saving the whole world. It can be difficult to let go of the top-down approach, to stop putting all our efforts into trying to change government policies or get the ‘right’ people elected, as if this would somehow solve our problems.

We need to get down to the business of doing the things on the ground that matter, and to look after our own local reality. We can expect considerable opposition from those who have long benefited from the status quo, but if enough people are involved, change can become unstoppable. It won’t solve our problems in the sense of allowing us to continue any kind of business as usual scenario, and it won’t prevent us from having to address the consequences of overshoot, but a goal to move us through the coming bottleneck with a minimum amount of suffering is worth striving for.

This article addresses just one of the many issues discussed in Nicole Foss’ new video presentation, Facing the Future, co-presented with Laurence Boomert and available from the Automatic Earth Store. Get your copy now, be much better prepared for 2014, and support The Automatic Earth in the process!

Home › Forums › Crash on Demand? A Response to David Holmgren