This is a guest article by Joanna Bailey

The Original Department of Subsistence Homesteads

Between 1933 and 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal created thirty-four communities under the Division of Subsistence Homesteads (DSH). The DSH, funded at $25 million, pledged to organize pilot programs showing how the country could benefit from semirural neighborhoods with part-time farming.

Each project would be initiated at the state level and administered through a nonprofit corporation. Successful applicants would be offered a combination of part-time employment opportunities, fertile soil for part-time farming, and locations connected to the services of established cities. DSH director Milburn L. Wilson stated:

“A subsistence homestead denotes a house and out buildings located upon a plot of land on which can be grown a large portion of foodstuffs required by the homestead family. It signifies production for home consumption and not for commercial sale. In that it provides for subsistence alone, it carries with it the corollary that cash income must be drawn from some outside source. The central motive of the subsistence homestead program, therefore, is to demonstrate the economic value of a livelihood which combines part-time wage work and part-time gardening or farming.”

When word of these projects reached people desperate for a lifeline out of the poverty and turmoil brought on by the Great Depression, thousands wrote letters of interest. Most of these heartbreaking pleas were from people who didn’t understand that the DSH projects weren’t meant to be a relief program for the unemployed and destitute. The new communities were categorized as to what group of workers they would be helping in the following manner:

“Stranded workers” – Intended to help logging communities at risk due to declining timber supplies, or miners facing economic-related shutdowns, etc.

“Farm” projects” – Intended to help farm families that had been struggling to work poor land.

“Industrial” homesteads” – Redistributed families from congested urban areas into the exurban countryside.

The Cumberland Homesteads project in Tennessee was one of the larger developments, at 10,000 acres. Successful applicants helped clear the land, selling the timber to defray building expenses, and milling some for the community structures. Most project plans allowed for shared spaces and buildings, including pastures, barns, and schools, since maintaining a strong sense of community was one of the basic tenets of the DSH homestead program.

Some factors taken into consideration in reviewing applicants were ‘neighborliness’ and ‘deportment of children’. In some areas, employment opportunities were provided by an existing industry, but others were considered in tandem with new factories or a cash crop to be farmed as a cooperative venture.

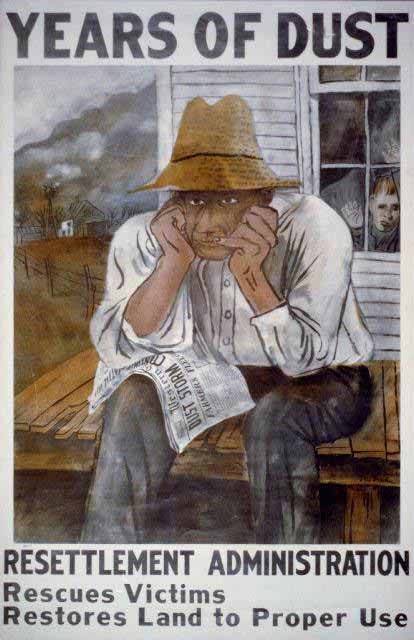

The DSH existed independently for only two years before being subsumed by the Resettlement Administration (RA), which survived for another two years before transitioning into the Farm Security Administration (FSA) and then into the Federal Public Housing Authority (PHA). As happens with many ‘big government’ initiatives, turf battles, bureaucratic slowdowns, political & personal conflicts of interest, all combined to make the DSH problematic from an administration perspective.

Once the visionaries initially involved at the beginning of the project grew impatient, frustrated, and finally moved on, the homestead program was shuffled from agency to agency, finally being discontinued by 1936. Most of the DSH communities shared the eventual fate of the one built in my state, near Longview, WA, with the federal government removing itself from the project’s operations in the early 40’s, leaving the association free to function as it saw fit.

Some people sold their properties to non-homesteaders, but a few remain relatively intact, with historical documentations and celebrations of “Homesteader Days”. Given the enthusiastic ground-level response to the DSH program, it seemed an expansion and continuation would have been very welcome to those families taking advantage, but by then the prospect of a coordinated “war effort” leading to economic revitalization through manufacturing trumped the political will for “homey” solutions.

More information about the original DHS can be found in Robert Carriker’s detailed and informative book,

as well as the following online resources:

- Subsistence Homesteads article, published Jan. 1934 in Survey Graphic magazine

- List of New Deal Homestead and Resettlement Communities

- News article about the Longview, WA project

- Cumberland Homesteads website

- News article c.1934 about the DSH

Reinventing the Department of Subsistence Homesteads

The original DSH was a top-down, built-from-scratch, fully government run and funded initiative. The homestead communities were meant to be model settlements (populated by carefully selected families), using all the resources the federal government could bring to bear, architects, agricultural experts, social planners, and the like. The hope was that these successful endeavors would inspire private corporations to invest in similar communities, leaving the government to ease itself out of the homesteading business altogether.

Some of the most functional elements of these projects were a result of local involvement at every level, from site planning to homesteader selection. A revived DSH would eschew federal involvement in favor of completely local and regional coordination under an umbrella organization.

There are already many community and homestead renewal movements underway across the country, and regional entities could easily work together once founding principles were enacted. A generalized real-life scenario under the new Department of Subsistence Homesteads is presented below, along with some loosely-grouped potential department branches that could utilize organizations or institutions which are currently active in any given community (organizations in my area will be used as examples).

Local Resources of the Education Branch: Whatcom Folk School, Whatcom County Extension, WSU-Mount Vernon Research Center, Country Living Expo

A young couple, mortgaged to an urban house with a decent-sized yard, decide to offset rising food costs and cuts in work hours by growing more of their own food. Having heard about the new Department of Subsistence Homesteads, they contact their regional coordinator, who comes to their house for an informational appointment. They sign up for Homesteading 101 through the area Folk School, which provides them information and directs them to further resources to assess their options.

Local Resources of the Community Branch: Sustainable Connections, Transition Whatcom, Bellingham Urban Gardeners, Washington State Grange

Local Resources of the Legal Branch: Maine’s Local Food and Self-Governance Ordinance, Farm to Consumer Legal Defense Fund

After being contacted by their neighborhood community coordinator, the couple joins the local grange (which is holding their monthly potluck soon, as posted on their online bulletin board). In addition, they are put in contact with representatives from local branches of organizations that specialize in legal information and aid, such as the Farm-to-Consumer Legal Defense Fund. This organization makes them aware of their rights as emerging farmers as the rights of customers to access their product directly.

Local Resources of Funding Branch: Whatcom Educational Credit Union, Whatcom Community Foundation, Kulshan Community Land Trust

They learn that their household could easily support raised bed gardening, a laying flock, some fruit trees, and, with a little work, a pig for meat or a dairy goat. They apply for a micro-loan from the state bank/community trust foundation that will pay for building supplies and soil amendments. With advice from the county extension, and some labor assistance obtained by bartering with a neighbor, they build the flock and garden infrastructure.

After a few years of successful urban homesteading, they decide to explore new initiatives being promoted through the DSH. It turns out that, with labor from the regional trade school and funding from the state bank (plus community trust and other local capital), DSH has been reclaiming suitable abandoned/foreclosed housing in semi-rural areas outside town, with an emphasis on contiguous properties for community resettlement.

Funding is in place for a feed mill that will source ingredients from larger farms in the state, process and package the finished products for distribution in the area.

A coordinating organization under the DSH umbrella has been working to bring the new mill up to speed in tandem with the influx of homesteaders moving to the reclaimed housing, providing cash wages to homesteaders and a local pool of workers to the new mill. The rise of subsistence homesteading means a steady need for quality animal feed, providing a good return on capital invested in the new venture. Job stability means homestead loans will be repaid, and homesteaders will enjoy food security and community life.

Local Resources of the Re-localization Branch:

- Scratch and Peck Feed,

- Growing Washington CSA,

- Northwest Agriculture Business Center,

- Grow Northwest

After reviewing the available resources, one of the couples decides to start a micro-dairy with another community member. Reworked food and zoning laws make homestead food production much easier to share with the wider community, so the micro-dairy will provide milk for the fifteen nearest households. The county extension supplies in-depth education and consultation, and meetings with past and present local dairy farmers give a look at the hands on reality of this venture.

A building party is planned, and a combination of bartered labor and materials, bank and donor funding, volunteers from the “Homesteads for Humanity” and apprentice builders program are used to construct a milk processing room adjoining the community barn.Eventually our couple realizes the hard work of homesteading is proving to be a challenge as they grow older. A younger household (perhaps the one living in the couple’s former urban homestead?) has posted a request for internship on community bulletin boards, and are now set to move in to guest quarters on the rural homestead.

A trial period of hands on practice while learning from the older couple leads to ownership transition. The older couple returns to a more urban setting, where they can continue to work part time and grow food while enjoying the convenience of town life.

Now that they have more time to share, they work on various DSH committees, help coordinate the expanding rural transit system, teach a few Homesteading 101 classes, etc. In this manner, the Subsistence Homestead program will sustain itself over many years and many generations, as individuals and families reciprocate within their community.

The specific details of how a new Subsistence Homestead Department and Program can be implemented will obviously differ across regions/communities and over time. Some regions will be able to develop the program on a relatively large-scale across many cities and towns in the U.S., and perhaps even states.

Others will have to take a much smaller-scale approach. Either way, there is no doubting that there are plenty of existing resources available for communities to draw upon in their attempts to revive the program, and tailor it to fit the abilities and needs of their local populations in the assuredly unique times of our future.

Home › Forums › Reviving the Department of Subsistence Homesteads