Russell Lee South Side market, Chicago 1941

“There’s still this fear of ‘everything is going to fall apart.'”

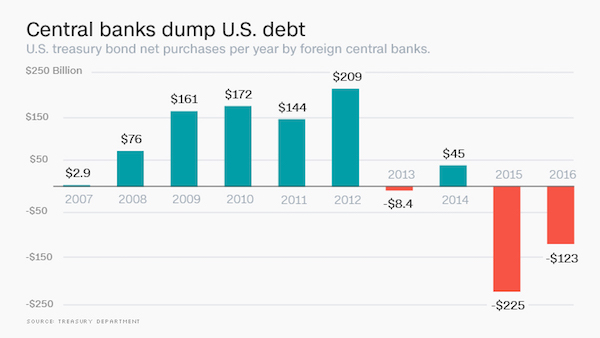

• US Debt Dump Deepens In 2016 (CNN)

China, Russia and Brazil sold off U.S. Treasury bonds as they tried to soften the blow of the global economic slowdown. They each sold off at least $1 billion in U.S. Treasury bonds in March. In all, central banks sold a net $17 billion. Sales had hit a record $57 billion in January. So far this year, the global bank debt dump has reached $123 billion. It’s the fastest pace for a U.S. debt selloff by global central banks since at least 1978, according to Treasury Department data published Monday afternoon. Treasuries are considered one of the safest assets in the world, but some experts say a sense of panic about the global economy drove the selloff.

“It’s more of global fear than anything,” says Ihab Salib, head of international fixed income at Federated Investors. “There’s still this fear of ‘everything is going to fall apart.'” Judging by the selloff, policymakers across the globe were hitting the panic button often and early in the year as oil prices fell, concerns about China’s economy rose and stock markets were very volatile. In response, countries may be selling Treasuries to prop up their currencies, some of which lost lots of value against the dollar last year. By selling U.S. debt, central banks can get hard cash to buy up their local currency and prevent it from losing too much value.

Also, as investors have pulled money out of developing countries, central bankers seek to replenish those lost funds by selling their foreign reserves. The leader in the selloff: China. “We’ve seen Chinese central bank foreign reserves fall dramatically,” says Gus Faucher, senior economist at PNC Financial. “Their currency is under pressure.” Between December and February, China’s central bank sold off an alarming $236 billion to help support its currency, which China is slowly letting become more controlled by markets and less by the government. In March, China sold $3.5 billion in U.S. Treasury bonds, Treasury data shows. Experts say the sell off may be slowing down now that global concerns have eased. If anything, demand is still high for U.S. Treasury bonds – it’s just coming from private investors.

ZIRP and NIRP feed the casino.

• The Humungous Depression (Gore)

Economic depressions unfold slowly, which obscures their analysis, although they are simple to understand. Governments and central banks turn recessions into depressions, which are preceded by unsustainable expansions of debt untethered from the real economy. The reduction and resolution of excess debt takes time, and governments and central banks usually act counterproductively, retarding necessary adjustments and lengthening the adjustment, and consequently, the depression. If one dates the beginning of a depression from the beginning of the unsustainable expansion of debt that preceded it, then the current depression began in 1987. Newly installed chairman of the Fed Alan Greenspan quelled a stock market crash, flooding the financial system with fiat liquidity. It was a well from which he and his successors would draw repeatedly.

Throughout the 1990s he would pump whenever it appeared the market and the US economy were about to dump. In 1999, he pumped because the Y2K computer transition might adversely affect the economy and financial system (it didn’t). If one dates the beginning of a depression from the time when the benefits of debt are, in the aggregate, outweighed by its burdens, the depression began in 2000, with the implosion of the fiat-credit fueled, high-tech and Internet stock market bubble. Unsustainable debt and artificially low interest rates lower the rate of return on productive investment and saving, increasing the relative attractiveness of speculation. Central bankers and their minions refer to this as “forcing investors out on the risk curve,” crawling way out on a limb for fruitful returns. They have no term for when markets saw off the branch, as they did in 2000 and again in 2008.

Most people don’t see 2000 as the beginning of a depression, but Washington and Wall Street cloud their vision. Stock markets were once essential avenues for raising capital and valuing corporations. Since central bankers’ remit was broadened to their care and feeding, stock markets have become engines of obfuscation. The “wealth effect” supposedly justified solicitude for markets: a rising stock market would increase wealth, spending, and economic growth. For seven years a rising market has coexisted with an anemic rebound and one hears little about the wealth effect anymore. The stock market is the preeminent symbol of economic health, so keeping it afloat has become a political exercise. Sure, central bankers and governments know what they’re doing, just look at those stock indices.

“They impose a levy on the banking system that has to be paid by someone..”

• Negative Rates Are A Form Of Tax (MW)

Central banks have slashed interest rates to nothing. They have printed money on a vast scale. Where that has not quite worked, and if we are being honest that is most places, they now have a new tool. Negative interest rates. Across a third of the global economy, money you put in the bank does not only generate nothing in the way of a return. You actually get charged for keeping it there. That is already producing strange, Alice-in-Wonderland economics, where nothing is quite what it seems. Governments want you to delay paying taxes as long as possible, the mortgage company pays you to stay in the house, and cash becomes so sought after there is even talk of abolishing it. But the real problem with negative rates may be something quite different.

As a fascinating new paper from the St. Louis Fed argues, they are in fact a form of tax. They impose a levy on the banking system that has to be paid by someone — and that someone is probably us. That may explain why central banks and governments are so keen on them. Hugely indebted governments are always in the market for a new tax, especially one that their voters probably won’t notice. But it also explains why they don’t really work — because most of the economics in trouble, especially in Europe, are already suffocating under an impossible high tax burden. Negative interest rates have, like a fast-mutating virus, started to spread across the world. The Swiss first tried them out all the way back in the 1970s.

In June 1972 it imposed a penalty rate of 2% a quarter on foreigners parking money in Swiss francs amid the turmoil of the early part of that decade, but the experiment only lasted a couple of years. In the modern era, the ECB kicked off the trend in June 2014 with a negative rate on selected deposits. Since then, they have spread to Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland (again), and more recently Japan, while the ECB has cut even deeper into negative territory. They already cover about a third of the global economy, and there is no reason why they should not reach further. The Fed might be raising rates this year, but it is the only major central bank to do so, and if, or rather when, there is another major downturn, it may have no choice but to impose negative rates as well.

“..how can an interest rate be negative? Does it become a “disinterest rate”?

• The Negative Interest Rate Gap (Dmitry Orlov)

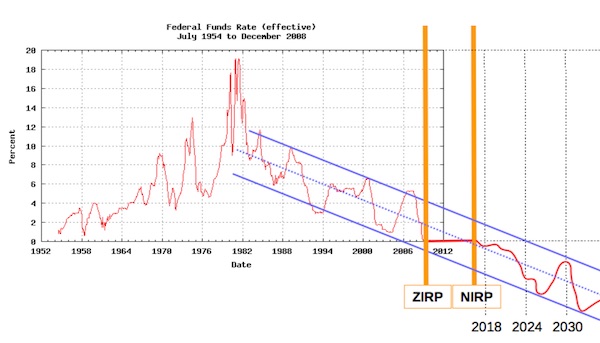

Back in the early 1980s the US economy was experiencing stagflation: a stagnant economy and an inflating currency. Paul Volcker, who at the time was Chairman of the Federal Reserve, took a decisive step and raised the Federal Funds Rate, which determines the rate at which most other economic players get to borrow, to 18%, freezing out inflation. This was a bold step, not without negative consequences, but it did get inflation under control and, after a while, the US economy stopped stagnating. Well, not quite. Wages didn’t stop stagnating; they’ve been stagnant ever since. But the fortunes of the 1% of the richest Americans have certainly improved nicely! Moreover, the US economy grew quite a bit since that time.

Of course, most of this growth came at the expense of staggering structural deficits and an explosion of indebtedness at every level, but so what? Sure, the national debt went exponential and the government’s unfunded liabilities are now over $200 trillion, but that’s OK. You just have to like debt. Keep saying to yourself: “Debt is good!” Because if everyone started thinking that debt is bad, then the entire financial house of cards would implode and we would be left with nothing. But once interest rates peaked in the early 1980s, they’ve been on a downward trend ever since, with little ups and downs now and again but an unmistakable overall downward trend.

The Federal Reserve had to do this in order to, in Fed-speak, “support economic activity and job creation by making financial conditions more accommodative.” Once it started doing this, it found that it couldn’t stop. The US had entered a downward spiral—of sloth, obesity, ignorance, substance abuse, expensive and disastrous foreign military adventures, bureaucratic insanity, massive corruption at every level—and under these circumstances it needed ever-cheaper money in order to keep the financial house of cards from imploding. And then, in late 2008, the Fed finally reached the ultimate target: the Fed Funds Rate went all the way to zero. This is known as ZIRP, for Zero Interest Rate Policy. And, unfortunately, it stayed there.

It stayed there, instead of continuing to gently drift down as before, because of a conceptual difficulty: how can an interest rate be negative? Does it become a “disinterest rate”? How can that work? After all, lenders are “interested” in lending because they get back more than they lend out (accepting some amount of risk); and depositors are “interested” in keeping money in banks because they get back more than they put in. And if these activities become “of zero interest,” why would lenders lend and depositors deposit? They wouldn’t, now, would they? They’d buy gold, or Bitcoin, or bid up real estate.

As long as we can see things only in terms of money nothing we do has any real value.

• The EU Has “Run Its Historical Course” (ZH)

None other than the former head of MI6 (the British Secret Intelligence Service) Richard Dearlove expressed his quite candid thoughts on the immigration crisis, as well as the possibility of a British exit from the EU during a speech recently at the BBC. The speech is well worth the listen. Here are some notable quotes from the speech as it relates to the immigration crisis. The former head of intelligence is quick to point out that despite what the public perception may be, the reality is that there are terrorists already among us.

“When massive social forces are at work, and mass migration is such a force, a whole government response is required, and a high degree of international cooperation.” “In the real world, there are no miraculous James Bond style solutions. Simply shutting the door on migration is not an option. History tells us that human tides are irresistible, unless the gravitational pull that causes them is removed. Edward Gibbon elegantly charted how Rome, with all it’s civic and administrative sophistication and military prowess, could not stop its empire from being overrun by the mass movement of Europe’s tribes.”

“We should not conflate the problem of migration with the threat of terrorism. High levels of immigration, particularly from the Middle East, coupled with freedom of movement inside the EU, make effective border conrol more difficult. Terrorists can, and do exploit these circumstances as we saw recently in their movement between Brussels and Paris, and to and from Syria. With large numbers of people on the move, a few of them will inevitably carry the terrorist virus.” A number of the most lethal terrorists are from inside Europe, including the UK. They are already among us.” “The EU, as opposed to its member states, has no operational counter-terrorist capability to speak of. Many of the European states look to the UK for training.”

“The argument that we would be less secure if we left the EU, is in reality rather difficult to make. There would in fact be some gains if we left, because the UK would be fully master of its own house. Counter-terrorist coordination across Europe would certainly continue, and the UK would remain a leader in the field. The idea that the quality of that cooperation depends in any significant way on our EU membership is misleading.” “Is the EU, faced with the problem of mass migration, able to coordinate an effective response from its member countries. Should the UK stay in and continue struggle for fundamental change, or do we conclude that the effort would be wasted, and that the EU in its extended form has run its historical course. For each of us, this is possibly the most important choice we may ever have to make.”

“Whether we will each be worse off, whether our national security might be damaged, even whether the economy might falter, and sterling be devalued, are subsidiary to the key question, which is whether we have confidence in the EU to manage Europe’s future. If Europe cannot act together to persuade a majority of its citizens that it can gain control of its migrant crisis, then the EU will find itself at the mercy of a populist uprising which is already stirring. The stakes are very high, and the UK referendum is the first roll of the dice in a bigger geopolitical game.”

Unlike Greece, Italy is so big it can make or break the EU. So goalposts are moved as they go along.

• Italy Wins Brussels’ ‘Flexibility’ On Debt Reduction Targets (FT)

Brussels has granted Italy “unprecedented” flexibility in meeting EU debt reduction targets, using its political leeway to the full as it cautiously polices the eurozone’s fiscal rule book. Italy has emerged as a big winner from the European Commission’s latest review of national budget policies, which is set to pull back from — or postpone — painful corrective measures it had the power to impose. The decisions have sparked an intense debate within the commission over what critics see as its record of tolerating fiscal lapses by countries such as France, Italy and Spain. Some officials were on Tuesday pushing to delay parts of the package to avoid punishing Spain and Portugal before Spain’s election on June 26.

The need for the debate on timing shows the commission under Jean-Claude Juncker has acted as a self-described political body, even at the risk of undermining the credibility of the eurozone’s strengthened fiscal regime. After months of heavy lobbying from Matteo Renzi, the Italian premier, Rome secured most of the “budgetary flexibility” it sought, helping it avoid so-called excessive deficit procedures for failing to bring down its debt levels fast enough. Italy would be allowed extra fiscal room equivalent to 0.85%of GDP — or about €14bn — this year compared with the target mandated under EU budget rules. Such “flexibility” approaches the 0.9% of GDP Italy demanded in drawn-out negotiations with Brussels.

Valdis Dombrovskis and Pierre Moscovici, the two European commissioners responsible for eurozone budget issues, said in a letter to Rome that “no other member state has requested nor received anything close to this unprecedented amount of flexibility”. Zsolt Darvas of the Bruegel think-tank said that “if the rules were taken literally” Italy would be placed under the excessive deficit procedure. Overall the EU fiscal rules “have very low credibility”, he added. “Many countries are violating the rules almost constantly from one year to the next.” Mr Renzi’s government is not completely in the clear, however. In exchange for the flexibility, the commission demanded a “clear and credible commitment” that Italy would respect its budget targets in 2017 to reduce the country’s high debt-to-GDP ratio, which stood at 132.7%of GDP last year.

Brilliant! What’s not to like? Can’t wait for the response.

• US Raises China Steel Taxes By 522% (BBC)

The US has raised its import duties on Chinese steelmakers by more than five-fold after accusing them of selling their products below market prices. The taxes specifically apply to Chinese-made cold-rolled flat steel, which is used in car manufacturing, shipping containers and construction. The US Commerce Department ruling comes amid heightened trade tensions between the two sides over several products, including chicken parts. Steel is an especially sensitive issue. US and European steel producers claim China is distorting the global market and undercutting them by dumping its excess supply abroad. The ruling itself is only directed at what is small amount of steel from China and Japan and won’t have much of an impact – but it is the politics of the ruling that’s worth noting.

It is an election year, and US presidential candidates have been ramping up the rhetoric on what they say are unfair trade practices by China. US steel makers say that the Chinese government unfairly subsidises its steel exports. Meanwhile China has been under pressure to save its steel sector, which is suffering from over-capacity issues because of slowing demand at home. China’s Ministry of Finance has not directly responded to the US ruling but on its website this morning it has said that China will maintain its tax rebate policy for steel exports as part of its efforts to help the bloated steel sector recover. These tax rebates are seen as favourable policies to shore up ailing steel companies in China, and to avoid massive job losses. Expect more fiery rhetoric from the US on China’s unfair trading practices soon.

“..China’s richest man — at least on paper — lost half of his wealth in less than half an hour.”

• Chinas Debt Bubble Is Getting Only More Dangerous (WSJ)

It would be like finding out Warren Buffett’s financial empire may have been, quite possibly, a sham. That’s what happened last year when China’s richest man — at least on paper — lost half of his wealth in less than half an hour. It turned out that his company Hanergy may well just be Enron with Chinese characteristics: Its stock could only go up as long as it was borrowing money, and it could only borrow money as long as its stock was going up. Those kind of things work until they don’t. The question now, though, is how much the rest of China’s economy has come down with Hanergy syndrome, papering over problems with debt until they can’t be anymore. And the answer might be a lot more than anyone wants to admit. Although we should be careful not to get too carried away here.

Hanergy is now a nothing that used debt to look like a very big something, while China’s economy actually is a very big something that is using debt to look even bigger. In other words, one looks like a boondoggle and the other a bubble. But in both cases, excessive borrowing — especially from unregulated “shadow banks,” such as trading firms — has made things look better today at the expense of a worse tomorrow. In Hanergy’s case, there will, of course, be no tomorrow. To step back, the first thing to know about Hanergy is that it’s really two companies. There’s the privately owned parent corporation Hanergy Group, and the publicly traded subsidiary Hanergy Thin Film Power (HTF). The latter, believe it or not, started out as a toymaker, somehow switched over to manufacturing solar panel parts, and was then bought by Hanergy Chairman Li Hejun.

And that’s when things really got strange. The majority of HTF’s sales, you see, were to its now-parent company Hanergy — and supposedly at a 50% net profit margin! — but it wasn’t actually getting paid, you know, money for them. It was just racking up receivables. Why? Well, the question answers itself. Hanergy must not have had the cash to pay HTF. Its factories were supposed to be putting solar panels together out of the parts it was getting from HTF, but they were barely running — if at all. Hedge-fund manager John Hempton didn’t see anything going on at the one he paid a surprise visit to last year. It’s hard to make money if you’re not making things to sell. But it’s a lot easier to borrow money and pretend that you’re making it. At least as long as you have the collateral to do so — which Hanergy did when HTF’s stock was shooting up.

Indeed, it increased 20-fold from the start of 2013 to the middle of 2015. But it was how more than how much it went up that raised eyebrows. It all happened in the last 10 minutes of trading every day. Suppose you’d bought $1,o00 of HTF stock every morning at 9 a.m. and sold it every afternoon at 3:30 p.m. from the beginning of 2013 to 2015. How much would you have made? Well, according to the Financial Times, the answer is nothing. You would have lost $365. If you’d waited until 3:50 p.m. to sell, though, that would have turned into a $285 gain. And if you’d been a little more patient and held on to the stock till the 4 p.m. close, you would have come out $7,430 ahead. (Those numbers don’t include the stock’s overnight changes).

Problem is: curb shadow banks and you curb local governments. Not at all what Xi is looking for.

• China To Curb Shadow Banking Via Checks On Fund House Subsidiaries (R.)

China plans to tighten supervision over fund houses’ subsidiaries and rein in the expansion of a sector worth nearly 10 trillion yuan ($1.53 trillion) as regulators target a key channel for so-called shadow banking to contain financial risks, according to a copy of the draft rules seen by Reuters. The Asset Management Association of China (AMAC) will set thresholds for fund houses to establish subsidiaries and use capital ratios to limit the subsidiaries’ ability to expand businesses, the draft rules said. Loosely-regulated subsidiaries set up by mutual fund firms have grown rapidly over the past year, managing 9.8 trillion yuan worth of assets by the end of March, according to the AMAC, and becoming a key channel for shadow banking activities.

Under the proposed rules, fund houses applying to set up subsidiaries must manage at least 20 billion yuan in assets excluding money-market funds, and have a minimum 600 million yuan in net assets. Current thresholds are much lower. The new rules would also require that a subsidiary’s net capital not be lower than the company’s total risk assets, while net assets must not be lower than 20% of its liability, in effect slashing the leverage ratio of the business. China’s prolonged crackdown on riskier practices in the lesser-regulated shadow banking system has taken on fresh urgency amid a growing number of corporate defaults as the economy struggles, and as top policymakers appear increasingly worried about the risks of relying on too much debt-fuelled stimulus.

You don’t have to watch it to know it’s a failure. That was clear from the start.

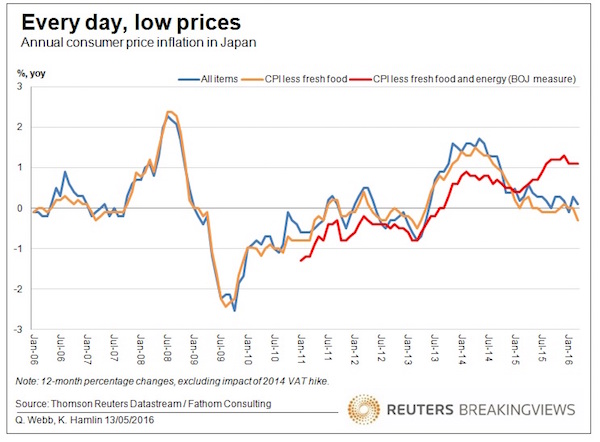

• Abenomics: The Reboot, Rebooted (R.)

Abenomics has over-promised and under-delivered. Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s bid to revive anaemic growth, reverse falling prices and rein in government debt has relied too heavily on the central bank and been sideswiped by a global slowdown. Keeping the project alive now requires fresh boldness. When he took office in December 2012, Abe set out to lift real economic growth to 2% a year, with consumer prices rising at the same rate. His main weapons were the famous “three arrows” of aggressive monetary policy, a flexible fiscal stance, and widespread structural reform. Abe has achieved some success. Unemployment is just 3.2%, a low last seen in 1997. In his first three calendar years in office, the economy expanded about 5% in nominal terms.

A weaker yen has helped deliver record corporate earnings; as of May 13 the Topix stock index had returned 70% including dividends. Prices have inched upwards. But the core targets remain out of reach. The IMF expects Japan’s GDP to grow just 0.5% this year. Even after cutting out volatile prices for fresh food and energy, the Bank of Japan’s preferred measure of inflation is running at just 1.1%. And the central bank keeps delaying its deadline for hitting the 2% target, which it now expects to reach in the year ending March 2018. Analysts still think that optimistic. Meanwhile, the yen has rallied unhelpfully and the BOJ faces accusations it is ineffective, after unexpectedly making no change to policy at its last meeting.

One snag is psychological: the deflationary mindset is hard to shake. Firms can borrow very cheaply yet hoard lots of cash and resist big pay rises. Workers are not pushy about wage hikes, and reluctant to spend. There were errors, too. Abe faced concerns that Japan’s government debt, at 2.4 times GDP, could become unsustainable. So he kept fiscal policy relatively orthodox, promising that taxes would cover public spending, excluding interest payments, by 2020. He hiked the country’s sales tax in 2014, denting growth and confidence. And he relied heavily on BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, whose institution now buys an extraordinary 80 trillion yen a year ($740 billion) of bonds. Meanwhile, structural reforms remain far from complete – in everything from encouraging more women into the workforce to reconsidering a deep aversion to immigration.

We can hope…

• Trump and Sanders Shift Mood in Congress Against Trade Deals (BBG)

Congress has embraced free trade for two generations, but the protectionist bent of the 2016 election campaign may mark the end of that era. The first casualty may be the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership, which was already facing a skeptical Congress. A European trade pact in the works may also be in trouble. Lawmakers from both parties are taking lessons from the insurgent campaigns of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, which have harnessed a wave of discontent on job losses by linking them to free-trade deals. Even Hillary Clinton has stepped up criticism of the pacts. While past presidential candidates have softened their stance on trade after winning election, the resonance of the anti-free-trade attacks among voters in the primaries may create a more decisive shift. Opponents of these deals are already sensing new openings.

“The gravity has shifted,” said Representative Marcy Kaptur, an Ohio Democrat. She said it could give new traction to proposals like one she’s put forth that would reopen trade deals with nations that have a trade deficit of $10 billion with the U.S. for three years in a row. The success of Trump and Sanders in Rust Belt states and elsewhere will make it even harder, if not impossible, for Congress to back TPP, even in a lame-duck session after the election. Lawmakers say it could also hamper a looming agreement between the U.S. and the EU if it looks like the next president would change course. “It’s a very heavy lift at this point,” said Representative Charlie Dent, a Pennsylvania Republican and longtime free-trade advocate, noting that all three remaining presidential contenders have expressed reservations about the TPP.

We never stood a chance. They’re oh so cunning and devious: “..smugglers ran their proceeds through [..] grocery stores..”. My question would be: how much of this went to the Erdogan family?

• Smugglers Made $5-6 Billion Off Refugees To Europe In 2015 (R.)

People smugglers made over $5 billion from the wave of migration into southern Europe last year, a report by international crime-fighting agencies Interpol and Europol said on Tuesday. Nine out of 10 migrants and refugees entering the European Union in 2015 relied on “facilitation services”, mainly loose networks of criminals along the routes, and the proportion was likely to be even higher this year, the report said. About 1 million migrants entered the EU in 2015. Most paid 3,000-6,000 euros ($3,400-$6,800), so the average turnover was likely between $5 billion and $6 billion, the report said. To launder the money and integrate it into the legitimate economy, couriers carried large amounts of cash over borders, and smugglers ran their proceeds through car dealerships, grocery stores, restaurants or transport companies.

The main organisers came from the same countries as the migrants, but often had EU residence permits or passports. “The basic structure of migrant smuggling networks includes leaders who coordinate activities along a given route, organisers who manage activities locally through personal contacts, and opportunistic low-level facilitators who mostly assist organisers and may assist in recruitment activities,” the report said. Corrupt officials may let vehicles through border checks or release ships for bribes, as there was so much money in the trafficking trade. About 250 smuggling “hotspots”, often at railway stations, airports or coach stations, had been identified along the routes – 170 inside the EU and 80 outside.

People understand things only when expressed in monetary terms. Maybe we need a real deep collapse to change that. Meanwhile, it looks like refugees make everyone rich except for themselves.

• Refugees Will Repay EU Spending Almost Twice Over In Five Years (G.)

Refugees who arrived in Europe last year could repay spending on them almost twice over within just five years, according to one of the first in-depth investigations into the impact incomers have on host communities. Refugees will create more jobs, increase demand for services and products, and fill gaps in European workforces – while their wages will help fund dwindling pensions pots and public finances, says Philippe Legrain, a former economic adviser to the president of the European commission. Simultaneously refugees are unlikely to decrease wages or raise unemployment for native workers, Legrain says, citing past studies by labour economists.

Most significantly, Legrain calculates that while the absorption of so many refugees will increase public debt by almost €69bn (£54bn) between 2015 and 2020, during the same period refugees will help GDP grow by €126.6bn – a ratio of almost two to one. “Investing one euro in welcoming refugees can yield nearly two euros in economic benefits within five years,” concludes Refugees Work: A Humanitarian Investment That Yields Economic Dividends, a report released on Wednesday by the Tent Foundation, a non-government organisation that aims to help displaced people.

A fellow at the London School of Economics, Legrain says he hopes the report will dispel the myth that refugees will cause economic problems for western society. “The main misconception is that refugees are a burden – and that’s a misconception shared even by people who are in favour of letting them in, who think they’re costly but it’s still the right thing to do,” said Legrain in an interview. “But that’s incorrect. While of course the primary motivation to let in refugees is that they’re fleeing death, once they arrive they can contribute to the economy.” While their absorption puts a short-term strain on public finances, Legrain says, it also increases short-term economic demand, which acts as a welcome fiscal stimulus in countries where demand would otherwise be low.

Home › Forums › Debt Rattle May 18 2016