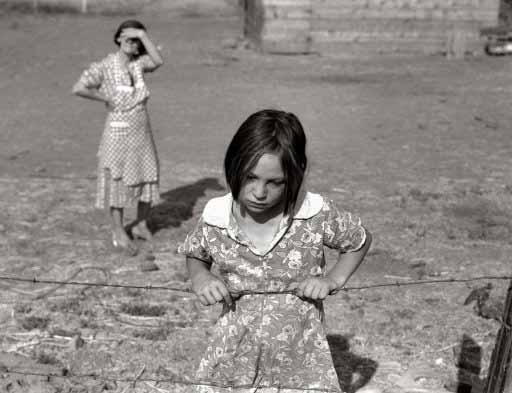

Dorothea Lange Social Security Tattoo August 1939

“Unemployed lumber worker goes with his wife to the bean harvest, Oregon”

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying things will happen in this order and timeframe. Just that they’re going to if central banks and treasury departments don’t up the ante. But they will. The question becomes more important now whether it’ll be enough to continue keeping their – presumed – demons at bay. They can’t go on forever. You can inflate asset price bubbles only so much. And then people will lose faith. So the order and timeframe is definitely an option.

Deflation is already here. Everyone’s talking about lower inflation numbers than expected everywhere, but prices have been pushed up artificially in so many ways and in so many places that, even given the fact that they all ignore what inflation really is, it’s getting profoundly absurd. Ironically, a few interesting lines this week came from an unexpected corner, the Telegraph editorial staff:

The last thing highly-indebted Britain wants is price deflation

The drop in the level of inflation revealed by the Office for National Statistics took some analysts and economists by surprise. It had been anticipated that CPI inflation would fall from its 2.7% mark in September to just 2.5% last month. Instead, it plunged to 2.2%, with the biggest downward contributions coming from transport.

It sparked questions – with much of continental Europe spiralling towards deflation and risking a repeat of Japan’s own crisis – over whether the whole world could be moving into deflationary mode.

At a time of near-double-digit increases in energy bills, this might seem a rather hard case to argue, yet the fact of the matter is that even in traditionally inflationary Britain, price pressures are easing fast.

[..] … on closer scrutiny, the sort of inflation currently being seen is mainly down to so-called “administered prices”, or prices which are being deliberately pushed up by government diktat either as part of the deficit reduction programme or green agenda.

Recently announced increases in energy bills are calculated by the Bank of England to have added 15 basis points to the CPI inflation outlook, a not insignificant amount but not enough to change the big picture on inflation. Most of the pressures right now are on the downside. Some European countries are, however, already in technical price deflation. Both Spain and Sweden, for instance, have recently reported an annual fall in prices, and even parts of Germany are experiencing month-on-month price contraction.

But then the last place a highly indebted nation such as Britain wants to be in is outright price deflation. There may not be much danger of that yet for the UK but the world as a whole seems very much to be drifting in that direction. This is worrying, not least because it implies continuation into the almost indefinite future of today’s very low interest rate environment. This doesn’t seem to be doing a great deal for demand but it is certainly putting a rocket under asset prices, creating bubbles and now fairly obvious misallocation of capital.

I’m indebted to the Telegraph for giving a name to something I have denounced several times in the past: governments raising “inflation” levels through taxes. My argument of course is that taxes should never be counted towards inflation, because doing so would mean inflation and deflation are easy as pie to control by governments (which they are very obviously not, or this “control” would be applied all the time and there would never be any inflation or deflation). Anyway, we can now call this phenomenon “administered prices”…

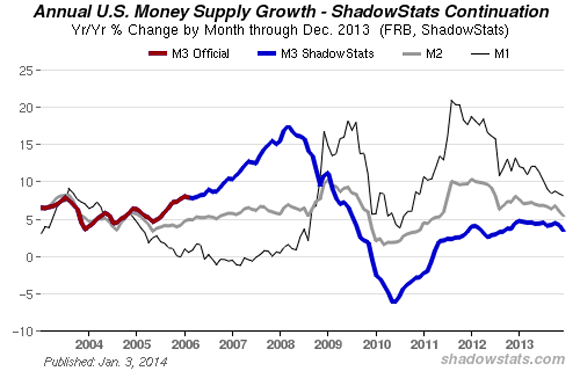

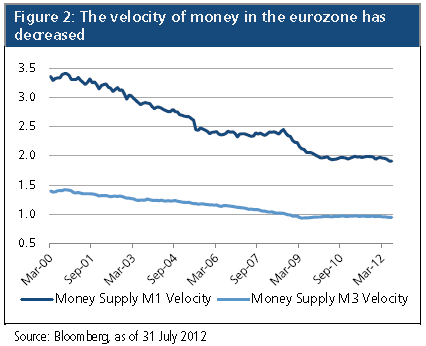

The paper neglects to note that this is one of the main ways in which Japan purports to fight its deflation: through higher taxes. That will not end well. Look, one more time: inflation means an increasing money supply and/or a higher velocity of money. No more, no less, and certainly not higher prices by themselves. If the money supply increases and/or the velocity of money does, prices will rise, but only as a consequence, and across the board. Nothing to do with taxes. And if for instance the Big Six UK energy companies raise their prices through fraudulent bookkeeping, that doesn’t – and shouldn’t – count towards inflation, but towards fraud.

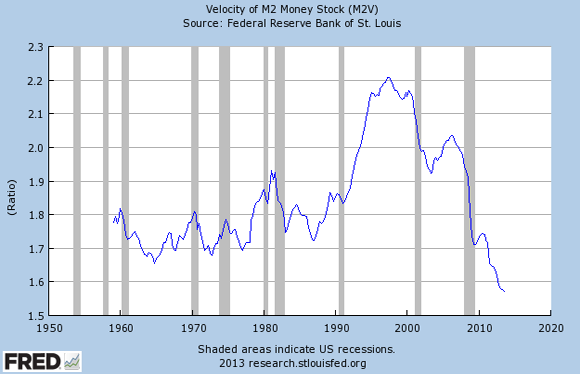

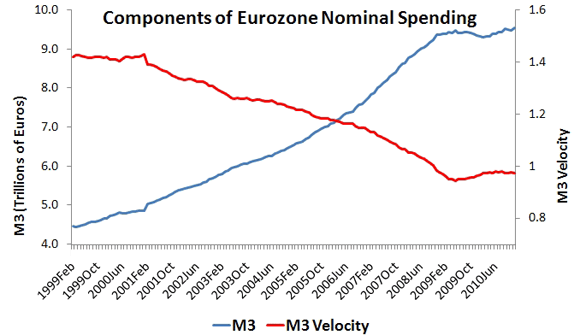

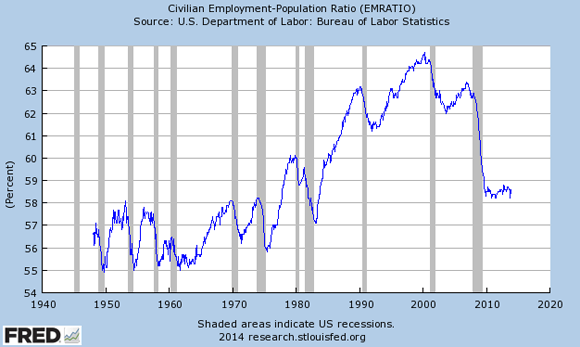

As for the velocity of money, you can see in this graph from Lacy Hunt and Van Hoisington (more on them later) that in the US, it’s come down in just 15 years from the highest point in more than 100 years to the lowest in the past 60 years. That is huge. That must have a tremendous influence on the economy, no matter what unemployment numbers are released, or what records stock markets set. As economic data go, the latter ones can only be entirely secondary to this:

When the velocity of money is that low, and we know there’s no huge increase in the money supply (though there may be in the monetary base), how can inflation numbers still be positive? Good question. You tell me.

That deflation (money supply and/or velocity of money shrinks and, only after that, prices and wages fall) is a growing worry, becomes clear through the following Bloomberg piece as well. It’s just that until now it remained hidden behind a veil of – mostly – central bank stimulus measures, which are behind various asset bubbles. Most of it is credit, backed by taxpayers, doled out to financial institutions and invested in stocks. Or, you know, the UK cabinet supplies cheap housing credit, people fall into the trap and buy their dream home, and, voila, “inflation” numbers go up. All nonsense designed to keep you from finding out what’s really going on, and to keep using your money to keep banks from going bankrupt. Bloomberg:

Central Banks Risk Asset Bubbles in Battle With Deflation Danger

Central banks are finding it’s easier to push up stock and home prices than it is to prevent inflation from falling short of their targets.

While declining costs for everything from gasoline to coffee can be good news for consumers, disinflation makes it harder for borrowers to pay off debts and businesses to boost profits. The greater danger comes when disinflation turns into deflation, which leads households to delay purchases in anticipation of even lower prices and companies to postpone investment and hiring as demand for their products dries up.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben S. Bernanke and his central-bank counterparts are trying to avert the deflationary danger by pumping up their economies with lower interest rates and monetary stimulus. They have bet the run-up in stock and home prices they’ve engineered would boost consumer and corporate confidence and spur faster growth and higher inflation. Now they’re having to maintain or intensify their aid – running the risk those efforts do more harm than good by boosting equity and property prices to unsustainable levels.

“You have a wall of liquidity” that’s “leading to asset inflation and eventually to bubbles,” Nouriel Roubini, chairman of Roubini Global Economics LLC, said Nov. 7 on Bloomberg Television’s “Street Smart.”

Global inflation will be about 2.8% this year, the second-lowest since World War II, amid high unemployment in developed nations and slowdowns in emerging markets, according to Bruce Kasman, chief economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co. in New York. Even after policy makers slashed interest rates and bought bonds, about two-thirds of 27 inflation-targeting central banks tracked by Morgan Stanley still are undershooting their goals or watching prices rise in the lower end of preferred ranges.

“We have seen, in the last months, deflationary tensions building up,” Laurent Freixe, executive vice president of Nestle SA, the world’s biggest food company, said in an Oct. 17 conference call. “There is no growth in the marketplace, so everyone is fighting for a share of a shrinking pie.” [..]

It might be more accurate to say we increasingly have multiple claims to the same pieces of the pie.

The central-bank largess is buoying world stock markets, as investors seek higher returns than they can get with government bonds. Japan’s Nikkei 225 Stock Average is up 40% this year. The MSCI World Index, which includes both emerging and developed country markets, has risen 19%. [..]

Home prices also are rising. The S&P/Case-Shiller index of property values in 20 U.S. cities climbed 12.8% in August from a year earlier, the fastest pace since February 2006. U.K. house prices increased for a ninth month in October, while apartment values in parts of Germany have jumped by an average of more than 25% since 2010. [..]

The easy money lacks punch because the “pipes” that carry stimulus from financial markets to the rest of the economy are “clogged,” Mohamed El-Erian, Pimco’s chief executive officer, said in an interview.

So why don’t you explain to us what Bernanke has done to unclog those pipes, Mo?

Commodity prices have fallen as demand from China and other developing economies has ebbed. The Washington-based IMF forecasts oil prices will slump 7.7% next year while non-fuel commodities will drop 2.9% in dollar terms. It also projects governments will keep cutting budgets, with the aggregate deficit of advanced nations at 4.5% of gross domestic product this year and 3.6% next year.

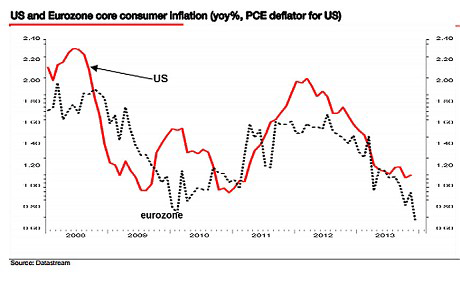

The region most at risk is the 17-nation euro area, where banks are deleveraging and wages are falling in nations including Spain. The ECB already is turning more aggressive after inflation slumped to a four-year low of 0.7% in October, less than half its target of just below 2%. Prices may not pick up any time soon, Draghi has warned. Unemployment is a record 12.2%, and the European Commission said last week it anticipates growth of just 1.1% in 2014.

“Deflation is not imminent, but it has to be on the mind of central bankers,” ECB Governing Council member Ewald Nowotny said yesterday in Vienna. The central bank still needs to do more because “a ‘Japanification’ of the euro area is a clear and present danger,” Joachim Fels, co-chief global economist at Morgan Stanley in London, said in a Nov. 10 report to clients.

Avoiding that fate may be hard. While Draghi has raised the possibility of charging banks to park cash at the ECB, colleagues have warned a negative deposit rate could hurt banks’ profitability and make them even less willing to lend. [..]

The Fed has found that expanding its balance sheet — now at a record $3.85 trillion — hasn’t been a panacea. Since the U.S. recession ended in June 2009, growth has fallen short of its predictions, and in nine of the last 10 estimates for 2013, policy makers have lowered their forecasts. Inflation, too, is lower than projected and has undershot the Fed’s 2% target starting in May 2012. The personal-consumption-expenditures index, the board’s preferred gauge, increased 0.9% in September from a year earlier, matching April for the lowest since October 2009. The rate will stay low in 2014, at about 1.25%, according to Sinai.

People are not spending, i.e. the velocity of money has fallen. A lot. And no, tempting them into more cheap credit is no solution for that. Because that means more debt. And it’s debt that is dragging economies down in the first place.

In Japan, the BOJ has had some success in battling deflation after swinging into action in April, when it pledged to double the monetary base through purchases of government bonds and other assets. Consumer prices excluding fresh food rose 0.7% in September from a year earlier, down from 0.8% in August, the fastest increase since November 2008. The yen has dropped about 20% against the dollar in the past year, boosting prices of imported goods. “Core inflation is now no longer negative,” said Jerald Schiff, deputy director of the IMF’s Asia-Pacific Department. That “is a major victory in the Japanese context.”

Yeah, but Japan does this through “administered prices”, prices which are being “deliberately pushed up by government diktat”. Again, if that could work, everybody would be doing it, and all the time.

While the aggressive actions that central banks have taken haven’t done all that much for global growth, they have boosted asset values worldwide, pushing home prices from Canada to Australia and Sweden to China to levels that may turn out to be unsustainable. Some Fed officials have pointed to costlier homes, farmland and bonds as causes for concern.

“We’ve seen real bubble-like markets again,” Laurence D. Fink, chief executive officer of BlackRock Inc., the world’s largest money manager with $4.1 trillion in assets, said at an Oct. 29 panel discussion in Chicago.

See, what these people are saying is in essence that Fed policies have not had the desired effect, or not enough of it, and now things are getting even worse, because they were so wrong, and deflation looms (even if many prefer for now to call it disinflation).

I have a problem with that. Which is that I, and others with me, have said for years that this would happen, that QE wouldn’t “help” the real economy. Just look up what debt deflation is, and it all becomes clear. It’s embarrasingly simple.

I mean, what exactly is the idea? That Ben Bernanke honestly tried to fight unemployment by stuffing the accounts Wall Street banks have with his own Fed, full of excess reserves? Because that’s all QE has resulted in in practical terms, isn’t it? I know that it has probably affected the “mood” in the markets somewhat as well, but is that really something Bernanke should fake? Is that part of his mandate as well, to fool people into believing things? I don’t see how.

Really, how wrong can a man in his position be before he’s pushed to look for alternative employment? And don’t look for any relief from Janet Yellen either, she’s been part of that same Fed all these years that continues to hand out $85 billion a month and has nothing to show for it other than some perceived moodswing and those bloated excess reserve accounts. Here’s what Yellen will say today in her nomination hearing before the Senate Banking Committee:

“A strong recovery will ultimately enable the Fed to reduce its monetary accommodation and reliance on unconventional policy tools such as asset purchases … I believe that supporting the recovery today is the surest path to returning to a more normal approach to monetary policy. [..] … the Fed has “made progress in promoting a strong and stable financial system, but here, too, important work lies ahead.” “Her approach is let’s do more QE now to get the job done faster,” said Laura Rosner, a U.S. economist at BNP Paribas SA in New York … “Yellen is repeating her commitment to getting the job done.”

In other words: Yellen’s not going to change a thing, despite that fact that everything the Fed has done so far has been a huge and costly failure as far as the real economy is concerned, which is what the Fed claims to be execute QE for.

I am not kidding you: this is a real problem for me. Because either those who keep claiming that Bernanke and the rest of the Fed board have made nothing but honest mistakes for years are right, and I am profoundly stupid – which I don’t think I am -, or I am right and the Fed is loaded with really stupid people. And I don’t believe that either.

There is a third option, however and of course: that the Fed has not at all been doing what they say they have, and it wasn’t a long line of mistakes, but something else altogether.

Found a fitting description of that too. In a highly interesting must read piece by Yanis Varoufakis. Fitting, also, because what the Fed does is the same thing the ECB does.

Ponzi Austerity – A Definition and an Example

Ponzi austerity is the inverse of Ponzi growth. Whereas in standard Ponzi (growth) schemes the lure is the promise of a growing fund, in the case of Ponzi austerity the attraction to bankrupted participants is the promise of reducing their debt, so as to liberate them from insolvency, through a combination of ‘belt tightening’, austerity measures and new loans that provide the bankrupt with necessary funds for repaying maturing debts (e.g. bonds).

As it is impossible to escape insolvency in this manner, Ponzi austerity schemes, just like Ponzi growth schemes, necessitate a constant influx of new capital to support the illusion that bankruptcy has been averted. But to attract this capital, the Ponzi austerity’s operators must do their utmost to maintain the façade of genuine debt reduction.

The obvious thing to do, under the circumstances, would be for Athens to default on the bonds that the ECB owned. But this was something that Frankfurt and Berlin considered unacceptable. The Greek state could default against Greek and non-Greek citizens, pension funds, banks even, but its debts to the ECB were sacrosanct. They had to be paid come what may. But how? This is what they came up with in lieu of a ‘solution’: The ECB allowed the Greek government to issue worthless IOUs (or, more precisely, short-term treasury bills), that no private investor would touch, and pass them on to the insolvent Greek banks.

The insolvent Greek banks then handed over these IOUs to the European System of Central Banks (through the so called ELA program of the ECB) as collateral in exchange for loans that the banks then gave back to the Greek government so that Athens could repay… the ECB. If this sounds like a Ponzi scheme it is because it is the mother of all Ponzi schemes.

[The creation of the first Ponzi Austerity scheme in Greece] is but one example of the vicious cycle of Ponzi Austerity that is being replicated incessantly throughout the Eurozone. Its stated purpose is to reduce debts. But debt is rising everywhere. Is this a failure? Yes and no. It is a failure in terms of the EU’s stated objectives but not in terms of the underlying ones.

For, in reality, the true purpose of the ‘bailout’ loans was to effect a cynical transfer of the Periphery’s bad debts from the books (mainly) of the Northern European banks to the shoulders (mainly) of Northern Europe’s taxpayers. Sadly, this cynical transfer, effected in the name of European ‘solidarity’, led to a death dance of insolvent banks and bankrupt states – sad couples that were sequentially marched off the cliff of competitive austerity – with the awful result that large sections of proud European nations were dragged into the contemporary equivalent of the Victorian Poorhouse.

Great article. Great novel view of things. And a great quote. Let’s get back to the Fed.

We can say for the Fed what Varoufakis says about the ECB (and the troika):

Fed policies. A failure. Yes and no. A failure in terms of stated objectives but not in terms of the underlying ones

Is the Fed trying to revive the US economy? If they are, they have been making lots of mistakes. Lots. Too many. All they’ve done is make mistakes. Other than creating a moodswing. But those are notoriously temporary. And this one depends on financial markets expecting more and more “free money“, not on an improving economy. What do they care, if the money keeps coming anyway?

This QE game has raised the Fed balance sheet by well over $3 trillion. And ballooned the too-big-to-fail-but-dead-broke banks’ accounts with the Fed by about the same amount.

But still, you have these respected analysts who keep on hammering the same single tune: it’s all mistakes, none of it happens on purpose. Like Lacy Hunt at Hoisington:

Federal Reserve Policy Failures Are Mounting

[..] … when an economy is excessively over-indebted and disinflationary factors force central banks to cut overnight interest rates to as close to zero as possible, central bank policy is powerless to further move inflation or growth metrics. The periods between 1927 and 1939 in the U.S. (and elsewhere), and from 1989 to the present in Japan, are clear examples of the impotence of central bank policy actions during periods of over-indebtedness.

[..] … the Fed’s forecasts have consistently been too optimistic, which indicates that their knowledge of how Large Scale Asset Purchases (LSAP) operates is flawed. LSAP obviously is not working in the way they had hoped, and they are unable to make needed course corrections. [..]

If the Fed were consistently getting the economy right, then we could conclude that their understanding of current economic conditions is sound. However, if they regularly err, then it is valid to argue that they are misunderstanding the way their actions affect the economy.

During the current expansion, the Fed’s forecasts for real GDP and inflation have been consistently above the actual numbers.

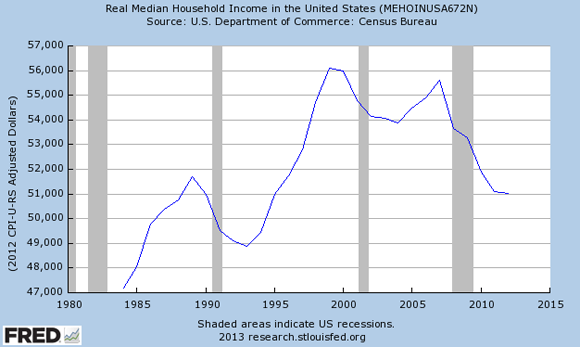

One possible reason why the Fed have consistently erred on the high side in their growth forecasts is that they assume higher stock prices will lead to higher spending via the so-called wealth effect. The Fed’s ad hoc analysis on this subject has been wrong and is in conflict with econometric studies. The studies suggest that when wealth rises or falls, consumer spending does not generally respond, or if it does respond, it does so feebly. During the run-up of stock and home prices over the past three years, the year-over-year growth in consumer spending has actually slowed sharply from over 5% in early 2011 to just 2.9% in the four quarters ending Q2.

Reliance on the wealth effect played a major role in the Fed’s poor economic forecasts. LSAP has not been able to spur growth and achieve the Fed’s forecasts to date, and it certainly undermines the Fed’s continued assurances that this time will truly be different. [..]

The standard of living, as measured by real median household income, began to stagnate and now stands at the lowest point since 1995. Additionally, since the start of the current economic expansion, real median household income has fallen 4.3%, which is totally unprecedented. [..]

Over-indebtedness is the primary reason for slower growth, and unfortunately, so far the Fed’s activities have had nothing but negative, unintended consequences.

Another piece of evidence that points toward monetary ineffectiveness is the academic research indicating that LSAP is a losing proposition. The United States now has had five years to evaluate the efficacy of LSAP, during which time the Fed’s balance sheet has increased a record fourfold.

It is undeniable that the Fed has conducted an all-out effort to restore normal economic conditions.

No, Lacy, that is not undeniable. I just did. And I have to wonder: why would you say that? Why would anyone? Do you really believe all you said there? That this entire group of more than average intelligent people make all these mistakes, and misinterpret all of these signals, despite having more and better access to data than anyone else, and you still don’t wonder if perhaps they’re not trying to do what they say they are? How can you claim to be an analyst if you don’t even question your most basic assumptions? How is that analysis and not apologism?

John Hussman writes some good market opinion, but he sort of falls into the same apology trap:

Leash the Dogma

It’s fascinating to hear central bankers talk about the economy, because in the span of a few seconds they can say so many things that simply aren’t supported by the evidence. [..] quantitative easing essentially proposes that rapid increases in the monetary base can achieve reductions in the unemployment rate. But when we examine the data, we find very little to support this view, regardless of whether the relationship is posed in terms of growth rates, levels, changes, coincident changes, or subsequent changes in unemployment. [..]

In my view, most of the response to quantitative easing reflects psychological factors rather than mechanistic ones. Certainly the scale of QE has been enormous, and suppressed short-term interest rates have undoubtedly motivated a reach-for-yield in more speculative assets. But it remains true that the amount of credit market debt in the U.S. is roughly 19 times the current size of the monetary base (with an average maturity of about 5-6 years), while the value of U.S. equities is easily over 6 times the monetary base.

So quantitative easing effectively relies on the extent to which investors shun zero-interest cash amounting to less than 3.9% of that available portfolio. In any environment where low-interest but liquid and non-volatile securities become desirable as even a small part of investor portfolios, quantitative easing is likely to lose its presumed ability to “support” financial markets. [..]

The truth is that Fed policy has the capacity to do enormous damage by adding fuel to asset price bubbles when investors are already inclined to take risk, yet has very little power to “support” asset prices when investors are inclined to avoid risk. The confidence that the Fed can, in all circumstances, drive asset prices higher is largely psychological – mostly due to misattributing the 2009 recovery to monetary policy instead of the move to end “mark to market” accounting. Yet even to the extent that stocks have been driven higher, there is very little evidence that the “wealth effect” on jobs and economic activity has been large. This is something that the Fed should have understood years ago. [..]

I continue to believe that it is plausible to expect the S&P 500 to lose 40-55% of its value over the completion of the present cycle, and suspect that whatever further gains the market enjoys from this point will be surrendered in the first few complacent weeks following the market’s peak.

See? they’re doing everything wrong. Ergo: boy, must they be stupid. Only, that second part is left out.

What I do find interesting is Hussman’s last claim: that it’s plausible to expect the S&P 500 to lose 40-55%. And he’s got a nice graph to show where things stand:

What can hold off a crash? Probably only more asset purchases by the Fed, and temporarily at that. Enter Janet Yellen stage left. Or does anyone doubt that the S&P would look completely different if QE had never happened? But even then. The people at the Fed are aware of the velocity of money data, they’re not nearly as thick as the analysts make them out to be. They know they’ve long lost the deflation battle. Maybe they can move people to take some of their money out of stocks and into something else, something that moves money around a bit more. Or maybe they can push some money or credit into the real economy through real estate prices. The problem there is that increasing credit doesn’t do much, if anything at all, that can be seen as positive. Not in an already hugely overindebted economy.

At some point you need to ask: stock market crash? What stock market? How is it still really a stock market if it hinges to such a large extent on the Fed pumping money into Wall Street banks? At the very least, you might question if the S&P still reflects an actual market at all, if that market is supposed to reflect what goes on in the economy, and obviously doesn’t. You might want to ask what purpose such a largely illusionary stock market has, what its use is within the larger economy. And while you’re at it, you might also want to answer what use the financial system as a whole is to the real economy, if all it does is squeeze money out of it.

We know the Fed can prop up the S&P for a while, and though we don’t know for how long, we do know that they’re running out of time. That’s what Hussman’s graph says. And wouldn’t we perhaps be better served by a market, and by data, that better reflect what’s going on in the real economy? So we know where we actually stand, and not what some moodswing or another says about that? The entire market, the entire financial system, has turned into a zombie that feeds on the American people’s life blood.

Let’s redefine all this talk, and call a spade a spade: The Federal Reserve defines and executes policies aimed at aiding the banking system, not the overall US economy. And although the Fed may claim that these are one and the same, it could have known – and it does – that they are not. The idea that supporting the banks equals supporting the US people, is just that: an idea. The Fed, more than anyone else, has access to the data that prove this. It knows how badly off the banks are.

So quit propping them up, throw open their books and let’s start restructuring. If you choose not to – here’s looking at you, Janet – stop pretending you’re acting on your dual mandate, that you have the people’s best interest at heart. There’s no evidence of that anywhere to be found in anything but words.

We may make it to Christmas without a market crash, with lots of happy expectations for record sales and a last bout of happy moodswing. That’s not that interesting. What is, is what’ll happen after that. We already have deflation, once you look past the words. And we have a stock market so grossly overvalued it can only be labeled a zombie. Record holiday sales are not going to materialize with the velocity of money at a 60-year record low. And then what, Janet? Increase QE? Double or nothing for the most costly “failure” in US history? All it takes is for people to keep believing, right?