DPC City Hall subway station, New York 1904

But don’t worry: nothing Bloomberg can’t spin: “Consumers are in a good mood coming into 2015, and we think that’s likely to continue..”

• US Consumer Spending Declined in December by Most in Five Years (Bloomberg)

Consumer spending fell in December as households took a breather following a surge in buying over the previous two months. Household purchases declined 0.3%, the biggest decline since September 2009, after a 0.5% November gain, Commerce Department figures showed Monday in Washington. The median forecast of 68 economists in a Bloomberg survey called for a 0.2% drop. Incomes and the saving rate rose. Consumers responded to early promotions by doing most of their holiday shopping in October and November, leading to the biggest jump in consumer spending last quarter in almost nine years. For 2015, a pick-up in wage growth will be needed to ensure households remain a mainstay of the expansion as the economy tries to ward off succumbing to a global slowdown.

“Consumers are in a good mood coming into 2015, and we think that’s likely to continue,” said Russell Price, a senior economist at Ameriprise, who correctly forecast the drop in outlays. “The prospects for 2015 look very encouraging.” Stock-index futures held earlier gains after the report. Projections for spending ranged from a decline of 0.6% to a 0.2% gain. The previously month’s reading was initially reported as an increase of 0.6%. For all of 2014, consumer spending adjusted for inflation climbed 2.5%, the most since 2006. Incomes climbed 0.3% in December for a second month, the Commerce Department’s report showed. The Bloomberg survey median called for a 0.2% increase. November’s income reading was revised down from a 0.4% gain previously reported. While growth in the world’s largest economy slowed in the fourth quarter, consumption surged, with household spending rising at the fastest pace since early 2006, a report from the Commerce Department last week showed.

Recovery.

• US Household Spending Tumbles Most Since 2009 (Zero Hedge)

After last month’s epic Personal Income and Spending data manipulation revision by the BEA, when, as we explained in detail, the household saving rate (i.e., income less spending ) was revised lower not once but twice, in the process eliminating $140 billion, or some 20% in household savings… there was only one possible thing for household spending to do in December: tumble. And tumble it did, when as moments ago we learned that Personal Spending dropped in the month of December by a whopping 0.3%, the biggest miss of expectations since January 2014 and the biggest monthly drop since September 2009!

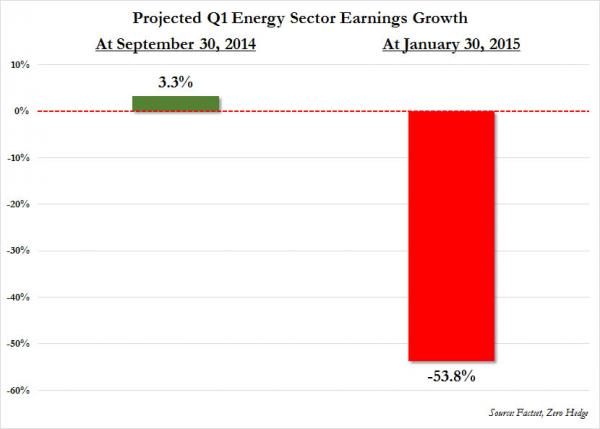

“By December 31, the estimated growth rate fell to -28.9%. Today, it stands at -53.8%.” Just a little off.”

• Q1 Energy Earnings Shocker: Then And Now (Zero Hedge)

Here is what Factset has to say about forecast Q1 energy earnings: “On September 30, the estimated earnings growth rate for the Energy sector for Q1 2015 was 3.3%. By December 31, the estimated growth rate fell to -28.9%. Today, it stands at -53.8%.” Just a little off. This is what a difference 4 months makes.

“XOM did the best with margins and accounting gimmickry it could under the circumstances..”

• Exxon Revenue, Earnings Down 21% From YoY, Sales Miss By $5 Billion (Zero Hedge)

Moments ago, following our chart showing the devastation in Q1 earning forecasts, Exxon Mobil came out with its Q4 earnings, and – as tends to happen when analysts take a butcher knife to estimates – beat EPS handily, when it reported $1.56 in EPS, above the $1.34 expected, if still 18% below the $1.91 Q4 EPS print from a year earlier. A primary contributing factor to this beat was surely the $3 billion in Q4 stock buybacks, with another $2.9 billion distributed to shareholders mostly in the form of dividends. Overall, XOM distributed $23.6 billion to shareholders in 2014 through dividends and share purchases to reduce shares outstanding.

This number masks the 29% plunge in upstream non-US earnings which were smashed by the perfect storm double whammy of not only plunging oil prices but also by the strong dollar. Curiously, all this happened even as XOM actually saw its Q4 worldwide CapEx rise from $9.9 billion a year ago to $10.5 billion, even though capital and exploration expenditures were $38.5 billion in the full year, down 9% from 2013. However, while XOM did the best with margins and accounting gimmickry it could under the circumstances, there was little it could do to halt the collapse in revenues, which printed at $87.3 billion, well below the $92.7 billion expected, and down a whopping 21% from a year ago. And this is just in Q4 – the Q1 slaughter has yet to be unveiled!

Set to get much worse.

• BP Hit By $3.6 Billion Charge, Cuts Capex On Oil Prices (CNBC)

BP revealed plans to cut capital expenditure (capex) on Tuesday, after it was hit by tumbling oil prices and an impairment charge of $3.6 billion. “We have now entered a new and challenging phase of low oil prices through the near- and medium-term,” said CEO Bob Dudley in a news release. “Our focus must now be on resetting BP: managing and rebalancing our capital program and cost base for the new reality of lower prices while always maintaining safe, reliable and efficient operations.” BP reported a replacement-cost loss of $969 million for the fourth quarter of 2014, after taking a $3.6-billion post-tax net charge relating to impairments of upstream assets given the fall in oil prices. On an underlying basis, replacement cost profit came in at $2.2 billion, above analyst expectations of $1.5 billion.

In the news release, BP said it was “taking action to respond to the likelihood of oil prices remaining low into the medium-term, and to rebalance its sources and uses of cash accordingly.” The company said that organic capex was set to be around $20 billion in 2015, significantly lower than previous guidance of $24-26 billion. Capex for 2014 came in at $22.9 billion, lower than initial guidance of $24-25 billion. “In 2015, BP plans to reduce exploration expenditure and postpone marginal projects in the Upstream, and not advance selected projects in the Downstream and other areas,” said the company.

“Attempting to sound an emollient note, Mr Varoufakis told the Financial Times the government would no longer call for a headline write-off of Greece’s €315bn foreign debt. Rather it would request a “menu of debt swaps..”

• Greece Finance Minister Varoufakis Unveils Plan To End Debt Stand-Off (FT)

Greece’s radical new government unveiled proposals on Monday for ending the confrontation with its creditors by swapping outstanding debt for new growth-linked bonds, running a permanent budget surplus and targeting wealthy tax-evaders. Yanis Varoufakis, the new finance minister, outlined the plan in the wake of a dramatic week in which the government’s first moves rattled its eurozone partners and rekindled fears about the country’s chances of staying in the currency union. After meeting Mr Varoufakis in London, George Osborne, the UK chancellor of the exchequer, described the stand-off between Greece and the eurozone as the “greatest risk to the global economy”.

Attempting to sound an emollient note, Mr Varoufakis told the Financial Times the government would no longer call for a headline write-off of Greece’s €315bn foreign debt. Rather it would request a “menu of debt swaps” to ease the burden, including two types of new bonds. The first type, indexed to nominal economic growth, would replace European rescue loans, and the second, which he termed “perpetual bonds”, would replace European Central Bank-owned Greek bonds. He said his proposal for a debt swap would be a form of “smart debt engineering” that would avoid the need to use a term such as a debt “haircut”, politically unacceptable in Germany and other creditor countries because it sounds to taxpayers like an outright loss. But there is still deep scepticism in many European capitals, in particular Berlin, about the new government’s brinkmanship and its calls for an end to austerity policies.

“What I’ll say to our partners is that we are putting together a combination of a primary budget surplus and a reform agenda,” Mr Varoufakis, a leftwing academic economist and prolific blogger, said. “I’ll say, ‘Help us to reform our country and give us some fiscal space to do this, otherwise we shall continue to suffocate and become a deformed rather than a reformed Greece’.” [..] Mr Varoufakis said the government would maintain a primary budget surplus — after interest payments — of 1 to 1.5% of gross domestic product, even if this meant Syriza, the leftwing party that dominates the ruling coalition, would not fulfil all the public spending promises on which it was elected. Mr Varoufakis also said the government would target wealthy Greeks who had not paid their fair share of taxes during the nation’s six-year economic slump. “We want to prioritise going for the head of the fish, then go down to the tail,” he said.

“The creation of the euro was a terrible mistake but breaking it up would be an even bigger mistake. We would be in a world where anything could happen:”

• Germany Will Have To Yield In Dangerous Game Of Chicken With Greece (AEP)

Finland’s governor, Erkki Liikanen, was categorical. “Some kind of solution must be found, otherwise we can’t continue lending.” So was the ECB’s vice-president Vitor Constancio. Greece currently enjoys a “waiver”, allowing its banks to swap Greek government bonds or guaranteed debt for ECB liquidity even though these are junk grade and would not normally qualify. This covers at least €30bn of Greek collateral at the ECB window. “If we find out that a country is below that rating – and there’s no longer a (Troika) programme – that waiver disappears,” he said. These esteemed gentlemen are sailing close to the wind. The waiver rules are not a legal requirement. They are decided by the ECB’s governing council on a discretionary basis. Frankfurt can ignore the rating agencies if it wishes. It has changed the rules before whenever it suited them.

The ECB may or may not have good reasons to cut off Greece – depending on your point of view – but let us all be clear that such a move would be political. A central bank that is supposed to be the lender of last resort and guardian of financial stability would be taking a deliberate and calculated decision to destroy the Greek banking system. Even if this were to be contained to Greece – and how could it be given the links to Cyprus, Bulgaria, and Romania? – this would be a remarkable act of financial high-handedness. But it may not be contained quite so easily in any case, as Mr Osborne clearly fears. I reported over the weekend that there is no precedent for such action by a modern central bank. “I have never heard of such outlandish threats before,” said Ashoka Mody, a former top IMF official in Europe and bail-out expert. “The EU authorities have no idea what the consequences of Grexit might be, or what unknown tremors might hit the global payments system. They are playing with fire.

The creation of the euro was a terrible mistake but breaking it up would be an even bigger mistake. We would be in a world where anything could happen. “What they ignore at their peril is the huge political contagion. It would be slower-moving than a financial crisis but the effects on Europe would be devastating. I doubt whether the EU would be able to act in a meaningful way as a union after that.” In reality, the ECB cannot easily act on this threat. They do not have the political authority or unanimous support to do so, and historians would tar and feather them if they did. The ground is shifting in Paris, Rome and indeed Brussels already. Jean-Claude Juncker, the European Commission’s president, yielded on Sunday, accepting (perhaps with secret delight) that the Troika is dead. French finance minister Michel Sapin bent over backwards to be accommodating at a meeting with Mr Varoufakis. There is no unified front against Greece. It is variable geometry, as they say in EU parlance.

“if Greece were to measure its debt using corporate accounting standards, which take account of interest rates and maturities, its debt burden could be lower than 70pc of GDP.”

• The Truth About Greek Debt Is Far More Nuanced Than You Think (Telegraph)

“Greek debts are unsustainable” Greece’s debts are, as a proportion of GDP, higher than most countries in the eurozone. But, by the same measure, the interest rates it pays on those debts are among the lowest in the currency bloc; the maturities on its loans are the longest. Eurozone countries calculate their debt according to the Maastricht definition, which means that a liability is valued in the same way whether it is due to repaid tomorrow or in 50 years’ time. Greece’s debts are 175pc of GDP under this definition. Some people have calculated that if Greece were to measure its debt using corporate accounting standards, which take account of interest rates and maturities, its debt burden could be lower than 70pc of GDP.

Greece’s debts might actually be a distraction from bigger issues. One is the requirement that, under the bailout conditions, Greece must run a primary surplus of 4.5pc of GDP. Another is the so-called fiscal compact, which requires EU governments with debts of more than 60pc of GDP to reduce the excess by one-twentieth a year. Are Greece’s debts unsustainable? Maybe and maybe not. Are these targets unattainable? Probably.

“The eurozone can withstand ‘Grexit’ now” This rather depends on what you mean by “withstand”. It is certainly true that the eurozone is in a better financial position to deal with Greece quitting or being ejected from the euro than when the last crisis flared up in 2012. It now has a rescue fund and has embarked on a quantitative easing programme. Even as yields on Greek sovereign debt have shot up in recent weeks, those in Spain, Portugal and Italy have stayed at or near record lows, suggesting the markets believe the potential fallout from Greece won’t spread to other southern European countries.

It is less clear that the eurozone could handle the existential threat posed by a Grexit. Membership of the currency bloc would no longer by irrevocable. The markets would scent blood. And the political and diplomatic repercussions are almost impossible to predict: Would it subdue or embolden the various anti-austerity and anti-euro factions that are gaining ground elsewhere in the region? Would it help foster an Orthodox alliance between Greece and Russia? Does Brussels really want to find out?

“Calling the meeting with Osborne a “breath of fresh air,” Varoufakis said: “we are highly tuned into finding common ground and we already have found it.”

• Greece Standoff Sparks Ire From US, UK Over Economic Risks (Bloomberg)

U.S. and British leaders are expressing frustration at Europe’s failure to stamp out financial distress in Greece and the risk it poses to the global economy. U.K. Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, whose government faces voters in three months, became the latest critics, following comments by Britain’s central banker, Mark Carney, and U.S. President Barack Obama. “It’s clear that the standoff between Greece and the euro zone is fast becoming the biggest risk to the global economy,” Osborne said after meeting Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis in London. “It’s a rising threat to our economy at home. Varoufakis travels to Rome Tuesday, along with Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, in a political offensive geared to building support for an end to German-led austerity demands, a lightening of their debt load and freedom to increase domestic spending even as they rely on bailout loans.

Tsipras, who went to Cyprus on Monday, also heads to Brussels and Paris. Calling the meeting with Osborne a “breath of fresh air,” Varoufakis said, “we are highly tuned into finding common ground and we already have found it.” Osborne’s comment came a day after Obama questioned further austerity. “You cannot keep on squeezing countries that are in the midst of depression,” he said on CNN. “When you have an economy that is in freefall there has to be a growth strategy and not simply an effort to squeeze more and more out of a population that is hurting worse and worse.” Greece’s economy has shrunk by about a quarter since its first bailout package in 2010. Tsipras was elected Jan. 25 promising the end the restrictions that have accompanied the aid that has kept it afloat.

The premier issued a conciliatory statement on Jan. 31, promising to abide by financial obligations after Varoufakis said the country won’t take more aid under its current bailout and wanted a new deal by the end of May. Before his appointment as finance minister, he advocated defaulting on the country’s debt while remaining in the euro. The Greek finance minister told bankers in London he wants the country’s “European Union-related” loans to be restructured, leaving debt to the IMF and the private sector intact. “A priority for them is to address the high level of debt,” said Sarah Hewin, head of research at Standard Chartered, who was at the meeting. “They’re looking to restructure EU bilateral loans and ECB loans and leave IMF and private-sector debt alone. At the moment, they’re working at a broad case without being specific on how this restructuring will take place.”

“Varoufakis knows as much about this subject “as anyone on the planet,” Galbraith says. “He will be thinking more than a few steps ahead” in any interactions with the troika.”

• Varoufakis Is Brilliant. So Why Does He Make Everyone So Nervous? (Bloomberg)

Yanis Varoufakis, Greece’s new finance minister, is a brilliant economist. His first steps onto the political stage, though, didn’t seem to go very smoothly. Before joining the Syriza-led government, Varoufakis taught at the University of Texas and attracted a global following for his blistering critiques of the austerity imposed on Greece by its international creditors. Among his memorable zingers: Describing the Greek bailout deal as “fiscal waterboarding” and comparing the euro currency to the Hotel California, as in, “You can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.” His social-media followers seem to love the fiery rhetoric—but investors and European Union leaders are clearly less enthusiastic. Greek stock and bond markets tanked on Jan. 30 after Varoufakis said the new government would no longer cooperate with representatives of the troika of international lenders who’ve been enforcing the bailout deal.

At an awkward Jan. 30 meeting with Jeroen Dijsselbloem, head of the Eurogroup of EU finance ministers, Varoufakis appeared to make things worse by calling for a conference on European debt. “This conference already exists, and it’s called the Eurogroup,” an obviously irritated Dijsselbloem told reporters afterwards. The reaction from Berlin was even frostier, with Finance Minister Wolfgang Schaeuble saying Germany “cannot be blackmailed” by Greece. Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras appeared to be scrambling to contain the damage. “Despite the fact that there are differences in perspective, I am absolutely confident that we will soon manage to reach a mutually beneficial agreement, both for Greece and for Europe as a whole,” he said on Jan. 31. But Varoufakis stayed on the offensive, with blog posts accusing news media organizations of inaccurate reporting and a BBC interview in which he blasted an anchorwoman for “rudely” interrupting him. “He may need some tips on how to handle himself on TV,” Steen Jakobsen, chief investment officer at Denmark’s Saxo Bank, wrote.

Is this really the guy Greece is counting on to negotiate a better deal with its creditors? Yes—and Varoufakis’s admirers say he shouldn’t be underestimated. “Yanis is the most intense and deep intellectual figure I’ve met in my generation,” says James K. Galbraith, an economist at the University of Texas who has worked closely with him. “Yanis knows far more about the current situation than some of the people he will be negotiating with,” adds Stuart Holland, an economist and former British Labour Party politician who has co-authored a series of papers with Varoufakis on the euro zone debt crisis. What’s more, Varoufakis’s academic specialty is game theory, the study of strategic decision-making in situations where people with differing interests try to maximize their gains and minimize their losses. Varoufakis knows as much about this subject “as anyone on the planet,” Galbraith says. “He will be thinking more than a few steps ahead” in any interactions with the troika.

“It’s clear that the stand-off between Greece and the euro zone is fast becoming the biggest risk to the global economy..”

• Greece’s Damage Control Fails to Budge Euro Officials (Bloomberg)

Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras’s damage-control efforts calmed investors while failing to budge European policy makers on his week-old government’s key demands. Officials in Berlin, Paris and Madrid rejected the possibility of a debt writedown raised by Greece’s anti-bailout coalition, as they held out the prospect of easier repayment terms, an offer that has been on the table since November 2012. Greek stocks and bonds rebounded following a conciliatory statement issued by the premier Saturday. He promised to abide by financial obligations, a prelude to a tour of European capitals, after Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis had prompted concern of a looming cash crunch by saying the country won’t take more aid under its current bailout and wanted a new deal by the end of May.

“The weekend statements sound less absurd than the noises from Athens last week,” Holger Schmieding, chief economist at Berenberg Bank in London, wrote in a note today. “However, the ideas of the new Greek government remain far removed from reality.” The Athens Stock Exchange index jumped 4.6%, led by Eurobank Ergasias. The yield on 10-year notes fell 22 basis points to 10.9% at 5:30 p.m. in Athens. Varoufakis was in London today, meeting Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne and then investors in sessions organized by Bank of America and Deutsche Bank.

“It’s clear that the stand-off between Greece and the euro zone is fast becoming the biggest risk to the global economy,” Osborne said in a statement after their talks. “It’s a rising threat to our economy at home.” Tsipras was in Cyprus before trips to Rome, Paris and Brussels, with Berlin not yet on the agenda. German Chancellor Angela Merkel wants to duck a direct confrontation and isolate him, a German government official said. In Nicosia, Tsipras repeated his finance chief’s call for an end to the committee that oversees the Greek economy. Dismantling the troika, which includes representatives of the European Commission, ECB and IMF, is “timely and necessary,” Tsipras said.

“They might be right; then again, back in 2008, US policy makers thought that the collapse of one investment house, Bear Stearns, had prepared markets for the bankruptcy of another, Lehman Brothers. We know how that turned out.”

• What is Plan B for Greece? (Kenneth Rogoff)

Financial markets have greeted the election of Greece’s new far-left government in predictable fashion. But, though the Syriza party’s victory sent Greek equities and bonds plummeting, there is little sign of contagion to other distressed countries on the eurozone periphery. Spanish 10-year bonds for example, are still trading at interest rates below those of U.S. Treasuries. The question is how long this relative calm will prevail. Greece’s fire-breathing new government, it is generally assumed, will have little choice but to stick to its predecessor’s program of structural reform, perhaps in return for a modest relaxation of fiscal austerity.

Nonetheless, the political, social, and economic dimensions of Syriza’s victory are too significant to be ignored. Indeed, it is impossible to rule out completely a hard Greek exit from the euro (“Grexit”), much less capital controls that effectively make a euro inside Greece worth less elsewhere. Some eurozone policy makers seem to be confident that a Greek exit from the euro, hard or soft, will no longer pose a threat to the other periphery countries. They might be right; then again, back in 2008, US policy makers thought that the collapse of one investment house, Bear Stearns, had prepared markets for the bankruptcy of another, Lehman Brothers. We know how that turned out.

True, there have been some important policy and institutional advances since early 2010, when the Greek crisis first began to unfold. The new banking union, however imperfect, and the European Central Bank’s vow to save the euro by doing “whatever it takes,” are essential to sustaining the monetary union. Another crucial innovation has been the development of the European Stability Mechanism, which, like the International Monetary Fund, has the capacity to execute vast financial bailouts, subject to conditionality. And yet, even with these new institutional backstops, the global financial risks of Greece’s instability remain profound. It is not hard to imagine Greece’s brash new leaders underestimating Germany’s intransigence on debt relief or renegotiation of structural-reform packages. It is also not hard to imagine eurocrats miscalculating political dynamics in Greece.

“‘The question’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘is which is to be master? The words or the girl?”

• Why The Bank Of England Must Watch Its Words (CNBC)

Once upon a time, it was only Alice who vanished down a rabbit hole into Wonderland. Nowadays, we’re all falling in head-first – thanks to a bunch of central bankers. But as we’re down here, in this inverted quantitative easing (QE) world, Mark Carney, governor of Britain’s central bank, should probably heed the words of Humpty Dumpty who warned Alice that she’d only gain control of reality if she became “master of words.” In Alice’s looking-glass reality, and maybe ours too, sense has become nonsense and nonsense sense – and not just because of asset bubbles. “‘The question’ said Humpty Dumpty, ‘is which is to be master?'” The words or the girl?

All central bankers worry about being imprisoned by their own words. But it will be preoccupying Carney’s thoughts more than ever as the Bank of England prepares its historic move to publish the minutes alongside the rate setting committee’s decision, due to begin in August. The frenzied over-analysis of the U.S. Federal Reserve’s choice of words could not have escaped his attention, with its decision to drop the phrase “considerable time” dominating newspaper columns and analysts notes. One economist complained privately that his job had morphed from monetary policy to structural linguistics.

Back in March 2011, Jean-Claude Trichet, the then president of the ECB got hemmed in by his own verbal signaling. Ironically, it was one of his favourite catch phrases: “strong vigilance”. It eventually forced his hand into making an ill-advised rate hike from 1% to 1.25% despite a deteriorating economic climate, duly sending the euro zone into recession. Of course, the ECB’s current boss, Mario Draghi, understands Humpty Dumpty’s lesson about making words perform the exact meaning one wants, though €1.1 trillion of QE and a crisis in Greece might now fully test “whatever it takes”.

“Government bond yields typically fall near the beginning of central-bank led programs intended to boost shaky economies, like the ECB’s bond-buying program, due to a shortage of bonds available to meet the central bank’s demand.”

• More Than 25% Of Euro Bond Yields Are Negative, But … (MarketWatch)

More than a quarter of eurozone bonds have negative yields — meaning investors are essentially paying for the privilege of lending money to a European sovereign government — but several analysts are betting that those yields will soon return to normal. The exact number of negative yielding sovereign bonds is 27%, according to Tradeweb data based on Monday’s closing rates. “We’re hoping that this is roughly the peak,” said David Keeble, head of fixed-income strategy at Crédit Agricole. “There’s certainly no reason to keep them in negative territory after five year [bonds].” So why are sovereign bond yields negative? Government bond yields typically fall near the beginning of central-bank led programs intended to boost shaky economies, like the ECB’s bond-buying program, due to a shortage of bonds available to meet the central bank’s demand.

But after two or three weeks, the effects of this stimulus programs should begin to take hold, Keeble said, resulting in stronger economic data. This in turn should whet the market’s appetite for risky assets like equities while safe investments like bonds fall out of favor. Keeble added that his prediction is contingent on the European Central Bank keeping monetary policy steady. “We’re not going to get any more rate cuts from ECB and i don’t think we’re going to see anymore QE,” Keeble added. In its latest forecast on eurozone bond yields, published Monday, Bank of America Merrill Lynch said they expect the yield on five-year eurozone bonds to fall from negative 0.05% to negative 0.10% in the second quarter, before rising in the third and fourth quarters.

Price discovery urgently needed.

• Draghi’s Negative-Yield Vortex Draws in Corporate Bonds (Bloomberg)

Credit markets are being so distorted by the European Central Bank’s record stimulus that investors are poised to pay for the privilege of parking their cash with Nestle. The Swiss chocolate maker’s securities, which have the third-highest credit ranking at Aa2, may be among the first corporate bonds to trade with a negative yield, according to Bank of America strategist Barnaby Martin. Covered bonds, which are bank securities backed by loans, started trading with yields below zero at the end of September. With the growing threat of falling prices menacing the euro-area’s fragile economy, some investors are calculating it’s worth owning Nestle bonds, even with little or no return. That’s because yields on more than $2 trillion of the developed world’s sovereign debt, including German bunds, have turned negative and the ECB charges 0.2% interest for cash deposits.

“In the same way that bunds went negative, there’s nothing, in theory, to stop short-dated corporate bond yields going slightly negative as well,” Martin said. “If investors want to park some cash, the problem with putting it in a bank or money market fund is potential negative returns, because of the negative deposit rate policy of the ECB.” Vevey-based Nestle SA’s 0.75% notes due October 2016 were quoted to yield 0.05% today, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. It isn’t the only company with short-dated bond yields verging on turning negative. Roche, the world’s largest seller of cancer drugs, issued €2.75 billion of bonds with a coupon of 5.625% in 2009. The notes, which mature in March 2016, pay 0.09%, Bloomberg data show. “The current yield is market-driven,” Nicolas Dunant, head of media relations at Basel, Switzerland-based Roche, said in an e-mail. “The bond has traded up because it has become increasingly attractive for investors in the current low-rate environment.”

The end of omnipotence.

• China Debt Party Nears The End Of The Road (MarketWatch)

Despite an interest-rate cut late last year, China’s economy has got off to a slow start, with weak factory and service-sector readings. The typical response to such data is to expect more monetary stimulus. But have we reached the point where rate cuts are no longer able to lift China’s debt-heavy economy? As China enters its third year of slowing growth, there is growing concern the debt reckoning cannot be kicked down the road any longer. Credit has been growing faster than the economy for six years, and there has always been a recognition this cannot continue indefinitely. Experience elsewhere would suggest countries coming off a multi-year, debt-fueled expansion could expect an inevitable hangover.

This would include everything from bad debts, bankruptcies and asset write-downs, together with currency weakness and perhaps a dose of austerity to restore order to finances. For China, however, we are led to expect a different economy — one where, even in a down cycle, you don’t get recessions but growth that only changes gear from double-digit to “just” 7%. While naysayers warn China’s debt binge is an accident waiting to happen, it never quite does: The bond market and shadow-banking sector have not experienced any meaningful defaults, nor has the banking system seen anything more than a limited increase in non-performing loans. China’s property market might look a lot like bubbles in the U.S., Spain or Japan at different times in history, yet here the ending is again benign, with a gentle plateauing of prices.

But elsewhere, it is possible to find evidence that an abrupt China slowdown is underway. In various global hard-commodity markets – where Chinese demand was widely acknowledged to have lifted prices in everything from iron ore to copper in the boom years — a major reversal is underway. A collection of industrial commodities has now reached multi-year lows. This suggests a lot of folk in China are already facing a hard landing. Signs are accumulating that the financial economy is now getting to a moment of reckoning. At home, slower growth puts added pressure on servicing corporate debt as profitability weakens. Overseas, tighter credit as the Federal Reserve retreats from quantitative easing means hot-money flows are no longer providing a boost to liquidity and are instead reversing.

“The slide in global oil prices and inflation has turned out to be even bigger than anticipated..”

• Global Deflation Risk Deepens As China Economy Slows (Guardian)

The risk of global deflation looms large for 2015 as surveys of China’s mammoth manufacturing sector showed excess supply and insufficient demand in January drove down prices and production. While the pulse of activity was livelier in Japan, India and South Korea, they shared a common condition of slowing inflation. “The slide in global oil prices and inflation has turned out to be even bigger than anticipated,” said David Hensley, an economist at JP Morgan, and central banks from Europe to Canada to India have responded by easing policy. “What is now in the pipeline will help extend the near-term impulse from energy to economic growth into the second half of the year.” A fillip was clearly necessary in China where two surveys showed manufacturing struggling at the start of the year.

The HSBC/Markit Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) inched a up a fraction to 49.7 in January, but stayed under the 50.0 level that separates growth from contraction. More worryingly, the official PMI – which is biased towards large Chinese factories – unexpectedly showed that activity fell for the first time in nearly 30 months. The reading of 49.8 in January was down from 50.1 in December and missed forecasts of 50.2. The report showed input costs sliding at their fastest rate since March 2009, with lower prices for oil and steel playing major roles. Ordinarily, cheaper energy prices would be good for China, one of the world’s most intensive energy consumers, but most economists believe the phenomenon is a net negative for Chinese firms because of its impact on ultimate demand.

Canada joins the currency war: “The Bank of Canada surprised the dickens out of everyone by cutting the overnight interest rate by 25 basis points.”

• Canada Mauled by Oil Bust, Job Losses Pile Up (WolfStreet)

Ratings agency Fitch had already warned about Canada’s magnificent housing bubble that is even more magnificent than the housing bubble in the US that blew up so spectacularly. “High household debt relative to disposable income” – at the time hovering near a record 164% – “has made the market more susceptible to market stresses like unemployment or interest rate increases,” it wrote back in July. On September 30, the Bank of Canada warned about the housing bubble and what an implosion would do to the banks: It’s so enormous and encumbered with so much debt that a “sharp correction in house prices” would pose a risk to the “stability of the financial system”.

Then in early January, oil-and-gas data provider CanOils found that “less than 20%” of the leading 50 Canadian oil and gas companies would be able to sustain their operations long-term with oil at US$50 per barrel. “A significant number of companies with high-debt ratios were particularly vulnerable right now,” it said. “The inevitable write-downs of assets that will accompany the falling oil price could harm companies’ ability to borrow,” and “low share prices” may prevent them from raising more money by issuing equity. In other words, these companies, if the price of oil stays low for a while, are going to lose a lot of money, and the capital markets are going to turn off the spigot just when these companies need that new money the most. Fewer than 20% of them would make it through the bust.

To hang on a little longer without running out of money, these companies are going on an all-out campaign to slash operating costs and capital expenditures. The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers estimated that oil companies in Western Canada would cut capital expenditures by C$23 billion in 2015, with C$8 billion getting cut from oil-sands projects and C$15 billion from conventional oil and gas projects. However, despite these cuts, CAPP expected oil production to rise, thus prolonging the very glut that has weighed so heavily on prices (a somewhat ironic, but ultimately logical phenomenon also taking place in the US). Then on January 21 – plot twist. The Bank of Canada surprised the dickens out of everyone by cutting the overnight interest rate by 25 basis points. So what did it see that freaked it out?

A crashing oil-and-gas sector, deteriorating employment, and weakness in housing. A triple shock rippling through the economy – and creating the very risks that it had fretted about in September. “After four years of scolding Canadians about taking on too much debt, the Bank has pretty much said, ‘Oh, never mind, we’ve got your back’, despite the fact that the debt/income ratio is at an all-time high of 163 per cent,” wrote Bank of Montreal Chief Economist Doug Porter in a research note after the rate-cut announcement. Clearly the Bank of Canada, which is helplessly observing the oil bust and the job losses, wants to re-fuel the housing bubble and encourage consumers to drive their debt-to-income ratio to new heights by spending money they don’t have.

As predicted, Australia joins the currency race to the bottom.

• Aussie Gets Crushed – How Much More Pain Lies Ahead? (CNBC)

With the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) leaving the door open to further rate cuts, the only way forward for the Australian dollar is down, say strategists. The Aussie plunged 1.9% against the U.S. dollar to $0.7655 on Tuesday after the central bank cut its benchmark cash rate by 25 basis points to a fresh record low of 2.25%. It was the currency’s biggest once-day loss since mid-2013, according to Reuters. “75 cents seems the natural progression point from here – I would expect that over the next two weeks if not sooner,” Jonathan Cavenagh, a currency strategist at Westpac told CNBC. “Beyond that, we’ll see how things unfold. If we see another rate cut, the Aussie could definitely be trading in the low-70 cent range,” he said.

The central bank struck a dovish tone in its policy statement highlighting below-trend growth and weak domestic demand in the economy, giving rise to expectations of additional easing. It also said the Aussie remained above fundamental value and that a lower exchange rate is needed to achieve balanced growth. In December, RBA Governor Glenn Stevens told local media that he would prefer to see the currency at $0.75 – levels not seen since early 2009. The Austrian dollar has already suffered a 26% decline against the U.S. dollar over the past two years, weighed by weak commodity prices and a stronger greenback. Paul Bloxham, chief economist for Australia and New Zealand at HSBC also expects the currency to come under further selling pressure. He forecasts the currency will head towards $0.70 going into 2016.