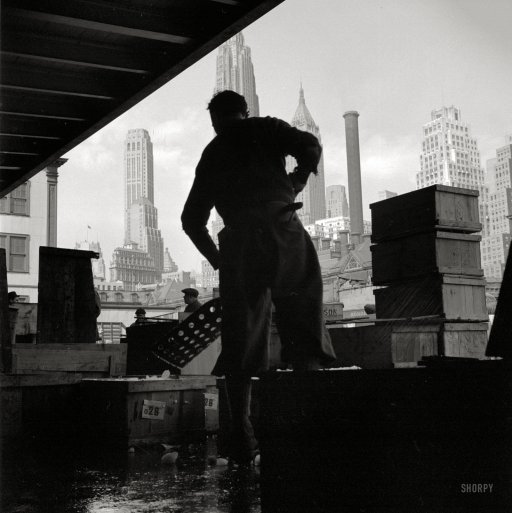

Gordon Parks A scene at the Fulton Fish Market, New York Jun 1943

In his 1944 play Huis Clos (loosely yet officially translated as No Exit, or Closed Door), French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre said: “L’enfer, c’est les autres.” Or: Hell is (the) other people. Which can be very true. And Sartre makes his point in a masterful way. He describes a group of people locked up together with no escape, and for eternity, who have a bitter go at each other. Something we all recognize. People can be a nuisance, and even drive one as far as suicide.

But then, the opposite is just as true. In more ways than one. Not only is hell the absence of other people (though I know there are monks who choose full separation), but heaven is the other people too. Or, as normal mortals would say: ‘(Wo)men, can’t live with them, can’t live without them’. Or something along those lines.

It’s who we are. We are social animals. Lions, not tigers. We’re tribal. We cannot give our lives meaning of and by ourselves, we need the other people to give it meaning. Though you may have gotten a different notion in your lifetime, the meaning of your life cannot be measured by something as fleeting as the size of your bank account. It cannot even by measured at all by ‘you’ yourself. Our lives derive their meaning from other people’s lives.

Over the Christmas season, many versions of Dickens’ Scrooge passed by our screens again. He’s a good example to use. In the beginning of the story, Scrooge is wealthy but his life has no meaning. That is Dickens’ core message. His life means nothing. It isn’t until he starts caring about others, and in the process giving – some of – his wealth away, that his life becomes meaningful. This is not a value judgment, and it isn’t for any religious or even philosophical reasons, it’s simple biology.

Religious leaders like Pope Francis and the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, get it. The ebola nurses and doctors get it. But that’s not nearly enough. We should all realize who we really are, and why. We all resemble Scrooge much more than we’re willing to admit. Problem is, we have no education system left to tell us about it. Our schools and colleges instead tell us to compete: our education focuses on the ‘Hell Is The Others’ side of our brains. The ‘Heaven Is The Others’ side is out of fashion.

And the education system is not the only problem. We also have a very big problem in that our present economic system doesn’t reflect, or fit in with, our natural-born psychology, our inbuilt mental set-up. Our economic system reflects, and appeals to, the part of our brain that tells us to outdo others, not cooperate with them.

Of course this is a complex issue, if only because our brains just happen to be made up of different parts. Still, if we are ever to enable the newest part of it, that which makes us human, and sets us apart from our non-human ancestors, from the simplest amoeba to far more advanced primates, to take control, if we are ever to achieve that, we will first have to recognize things for what they are. And then act on that.

Endless and forever competition from our earliest childhood days all the way to our graves clearly doesn’t seem the way to go. Look around you. It makes us destructive beings. It makes us unkind to each other, and distant from one another. Those are the very things that tear apart the social fabric our very biology says we need. If we don’t make a strong conscious effort to allow our ‘human brain’ to control our ‘animal brain’, we have no chance, we will be lost. Today, what we do is use our human intelligence to amplify the destructive properties of our animal brain.

This is evident in what we are doing to our living environment. We are at present no better than the yeast in the wine vat, who multiply at fast as they can until all the sugar is gone and then die off in the blink of an eye. Only, for us, the earth itself is both our wine vat and our sugar, and unlike the yeast we can do grave danger to our entire environment. We’re not just killing ourselves, we’re murdering just about everything around us.

A wonderful image of how this works, one that should make us think, was painted last week in the LA Times by James K. Boyce, economics professor at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

• Amid Climate Change, What’s More Important? Protecting Money Or People?

[..] .. it is too late to prevent climate change, no matter how fast we ultimately act to limit it. [We] now confront an issue that many had hoped to avoid: adaptation. Adapting to climate change will carry a high price tag. [..] Because adaptation won’t come cheap, we must decide which investments are worth the cost.

A thought experiment illustrates the choices we face. Imagine that without major new investments in adaptation, climate change will cause world incomes to fall in the next two decades by 25% across the board, with everyone’s income going down, from the poorest farmworker in Bangladesh to the wealthiest real estate baron in Manhattan. Adaptation can cushion some but not all of these losses. What should be our priority: reduce losses for the farmworker or the baron?

For the farmworker, and a billion others in the world who live on about $1 a day, this 25% income loss will be a disaster, perhaps the difference between life and death. Yet in dollars, the loss is just 25 cents a day. For the land baron and other “one-percenters” in the U.S. with average incomes of about $2,000 a day, the 25% income loss would be a matter of regret, not survival. He’ll find a way to get by on $1,500 a day. In human terms, the baron’s loss pales compared with that of the farmworker. But in dollar terms, it’s 2,000 times larger.

Conventional economic models would prescribe spending more to protect the barons than the farmworkers of the world. The rationale was set forth with brutal clarity in a memorandum leaked in 1992 that was signed by Lawrence Summers, then chief economist of the World Bank. The memo asked whether the bank should encourage more migration of dirty industries to developing countries and concluded that “the economic logic of dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest-wage country is impeccable and we should face up to that.” Climate change is just a new kind of toxic waste.

The “economic logic” of the Summers memo – later said to have been penned tongue-in-cheek to provoke debate, which it certainly did – rests on a doctrine of “efficiency” that counts all dollars equally. Whether it goes to a starving child or a millionaire, a dollar is a dollar. [..] A different way to set adaptation priorities is to count each person equally, not each dollar. This approach rests on the ethical principle that a healthy environment is a human right, not a commodity to be distributed on the basis of purchasing power, or a privilege to be distributed on the basis of political power.

This equity principle is widely embraced around the world, from the affirmation in the U.S. Declaration of Independence that people have an inalienable right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness,” to the guarantee in the South African Constitution that everyone has the right “to an environment that is not harmful to their health or well-being.” It puts safeguarding the lives of the poor ahead of safeguarding the property of the rich.

In the years ahead, climate change will confront the world with hard choices: whether to protect as many dollars as possible, or to protect as many people as we can.

It’s obvious. The choice is, as I wrote above, between human terms or dollar terms. In which dollar terms stands for choosing the primitive parts of our brain. Most likely, given the way we have organized our societies, our education systems and our economic systems, the rich part of the world will spend hundreds of billions protecting their sea-side villas, while entire poorer nations, and the people living in them, threaten to disappear.

In our own countries as well, that choice will be made, favoring well-to-do over poor. After all, what are the economic reasons for water-proofing a slum? Where 10,000 people can each afford to maybe contribute $100 to the work, while a ‘baron’ can easily afford $10 million to secure his summer home a few miles away?

In today’s world, it’s not even a question. But then in today’s world, money rules the political system, which should in an ideal world be holding a society together, not tearing it apart. Which it very much does. Our political systems separate the rich from the poor, like they’re not of the same species, like there’s nothing that ties them together.

It probably doesn’t even sound as a actual choice to you. You most likely think that these things go as they do, that ‘they’ have all the power anyway and there’s nothing you can do. But that doesn’t seem very human, does it, and certainly not very American, to just give up without a fight. And it’s starting to look as if you don’t stand up now for your self, your progeny and all other people, you needn’t bother anymore.

Then again, perhaps it’s not all that hard. We have a spectacularly failed economic system anyway, and we’re in dire need of a new one. So why not catch two birds with one stone (sorry, Tweetie, just an expression) and redo both our education systems and our economic systems, and make sure our adaptation to climate change gets organized on a one man one vote, instead of a one dollar one vote basis? It’s a place to start. Try and recognize which part of you, yourself, is a dumb predator and which part is a ‘social being human’. And pick the latter for all of your future decisions.

And teach yourself, and your kids, that Scrooge is you, we are all Scrooge, that’s what Dickens meant to say, and that the meaning of your life, too, derives its meaning from other people’s lives, not from itself. Once you got that down, you’re halfway there.

We tend towards thinking our ‘elected’ political leaders should, and will, take care of issues such as these, and in a fair way too. But in fact they’re the very last ones who will do so. Because they owe their positions to the very educational and economic systems that have ‘designed’ the way things are running out of hand.

We need to move, our societies, and the entire earth, need us to move to a ‘people’, as opposed to a ‘dollar’, point of view.

The separation between rich and poor doesn’t of course only come to the fore in climate change adaptation issues. We’re living today inside these narratives of an economic recovery, at the same time that poverty even in western societies rises fast. The rich are doing well, and that’s what we see reflected in ‘official’ economic numbers. But it’s all just pure predation.

What you can do is perhaps to vote for another party, but in many countries that’s not an option, the status quo has far too firm a handle on the entire political system. So you’re going to have to come up with something else, and if need be, take to the streets. Or the internet.

And as you do, think about Scrooge, and about to what extent his fictional, intentionally over the top caricaturized, persona reflects the real life you. As I said, once you got that down, you’re halfway there.