Jack Delano Main street intersection, Norwich, Connecticut 1940

“Few have lived as high on the hog as the Brits have.”

• Brexit Or Not, The Pound Will Crash (EvBB)

Status quo, as our generation know it, established in 1945 has plodded along ever since. It is true that it have had near death experiences several times, especially in August 1971 when the world almost lost faith in the global reserve currency and in 2008 when the fractional reserve Ponzi nearly consumed itself. While the recent Brexit vote seem to be just another near death experience we believe it says something more fundamental about the world. When the 1945 new world order came into existence, its architects built it on a shaky foundation based on statists Keynesian principles. It was clearly unsustainable from the get-go, but as long as living standards rose, no one seemed to notice or care. The global elite managed to resurrect a dying system in the 1970s by giving its people something for nothing.

Debt accumulation collateralized by rising asset values became a substitute for productivity and wage increases. While people could no longer afford to pay for their health care, education, house or car through savings they kept on voting for the incumbents (no, there is no difference between center left and right) since friendly bankers were more than willing to make up the difference. It is clear for all to see but the Ph.Ds. that frequent elitist policy circles that the massive misallocation and consumption of capital such a perverted system enables will eventually collapse on itself. Debt used to be productive, id est. self-liquidating, but now it is used for consumption backed by future income projections based on historical experience.

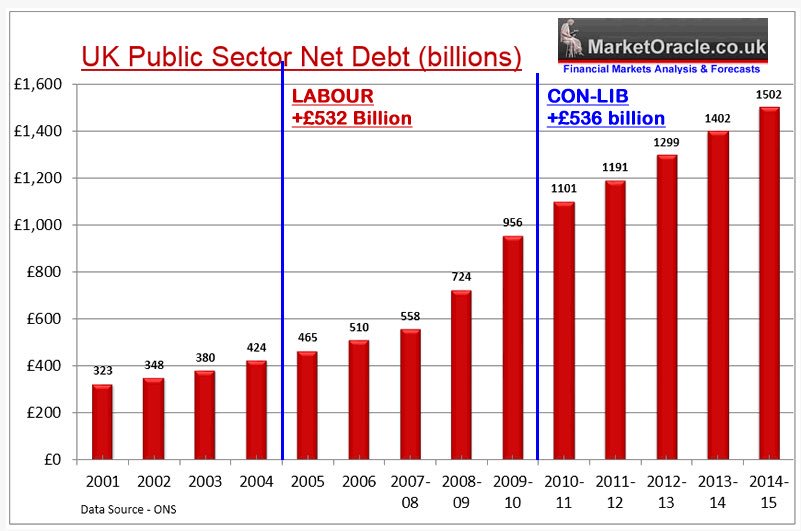

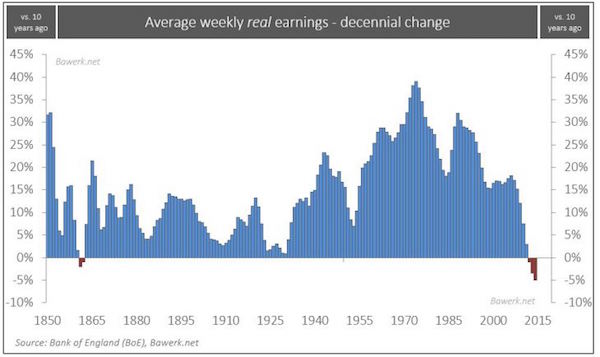

However, one should not extrapolate future income streams from a historical regime when the new one is fundamentally different. The promised incomes obviously never materialized and the world reached peak debt. The credit Ponzi is dead. Consider the following chart that depicts decennial change in average real earnings for the UK worker. It shows an unprecedented development. Not since the 1860s have the UK worker experienced falling real earnings over a ten-year period. Such dramatic change obviously does something to the so-called social contract people have been tricked into. People no longer believe in a brighter future and there is nothing more detrimental to a human being than that.

No longer vested in the status quo, people opt for radical change, hence; Brexit, Trump, Le Pen, Lega Nord, M5S. Old rules does not apply anymore. Over the next couple of years, we will experience a torrent of sea change, a lot of it unpleasant, but it will come nonetheless. In the social contract, immigration is OK when jobs are plentiful and people’s houses are worth more every year. Not so much when they are unemployed and without a house or even prospects of ever owning one. Corruption in the higher echelons of society is grudgingly accepted when the elite allegedly runs a system where incomes and productivity constantly moves upwards, but will not be tolerated as blue collar jobs are moved offshore.

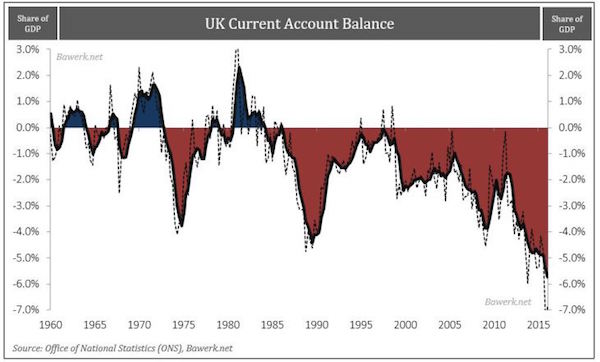

[..] So what does this mean for the UK specifically? Few have lived as high on the hog as the brits have. Their current account deficit at 6 per cent of GDP is reminiscent of countries heading into depressions. In the mid-1970s, the IMF had to bail them out and in the early 1990s, the infamous ERM regime collapsed as Soros made his billion. The pound got a pounding on the Brexit vote, but it was destined to fall anyways. The adjustment needed to correct this imbalance is not over and we should all expect a far weaker pound in the months and years ahead. Brexit only triggered what was already baked into the cake in the first place.

Stuck in BAU.

• BOE Chief Economist Haldane Calls For Big Post-Brexit Stimulus (G.)

The Bank of England’s chief economist has called for a big package of measures to support the UK’s post-Brexit economy, stressing the need for a prompt and robust response to the uncertainty. Andy Haldane made it clear the Bank’s monetary policy committee would do more than merely cut interest rates from their already record low of 0.5% when it meets in August. The Bank’s chief economist used a speech to warn that decisive action was required at a time when confidence had been dented by the shock referendum result. “In my personal view, this means a material easing of monetary policy is likely to be needed, as one part of a collective policy response aimed at helping protect the economy and jobs from a downturn.

“Given the scale of insurance required, a package of mutually complementary monetary policy easing measures is likely to be necessary. And this monetary response, if it is to buttress expectations and confidence, needs I think to be delivered promptly as well as muscularly. By promptly I mean next month, when the precise size and extent of the necessary stimulatory measures can be determined as part of the August inflation report round.” The Bank surprised the City when it left interest rates on hold at its July meeting held this week, but the minutes of the MPC’s discussions said most of its nine members thought an easing of policy would be required in August.

The tone and content of Haldane’s speech suggest that the MPC will use public appearances to make the case for strong action in August. Options include cutting interest rates to 0.25% or lower, restarting the Bank’s £375bn quantitative easing scheme and providing cut price loans to banks under the funding for lending scheme. [..] In a reference to the prison movie The Shawshank Redemption Haldane said: “I would rather run the risk of taking a sledgehammer to crack a nut than taking a miniature rock hammer to tunnel my way out of prison – like another Andy, the one in the Shawshank Redemption. And yes I know Andy did eventually escape. But it did take him 20 years. The MPC does not have that same ‘luxury’.”

This headline somehow seems to perfectly capture UK politics today. Whatever.

• Philip Hammond Promises ‘Whatever Measures’ To Stabilise Economy (Ind.)

Philip Hammond, the UK’s newly appointed chancellor of the exchequer, said the vote to leave the EU had “rattled confidence” and that he will take “whatever measures” needed to shore up the British economy. “The number one challenge is to stabilise the economy, send signals of confidence about the future, the plans we have for the future to the markets, to business, to international investors,” Hammond said in a Sky News interview. Hammond’s comments came ahead of a meeting later on Thursday of Bank of England policy makers who will debate whether to reduce the key interest rate for the first time since 2009.

The Bank’s governor, Mark Carney, is seeking to stave off further turmoil after the pound plunged and consumer confidence dropped to a 21-year low in the wake of last month’s decision to quit the EU. The chancellor, appointed to the role late on Wednesday by new prime minister, Theresa May, will meet Carney on Thursday morning “to make an assessment of where the economy is,” he said in a BBC TV interview. He added: “I think the governor of the Bank of England is doing an excellent job.”

It’s embarrassing to watch.

• Dow Extends Record Streak as US Stocks Post Weekly Gains (WSJ)

The Dow Jones Industrial Average hit its fourth consecutive closing high on Friday, rising 10.14 points, or less than 0.1%, to 18516.55. For the week, it gained 2%. The S&P 500’s rally put the index above the mean average of year-end targets from 18 analysts tracked by Birinyi Associates. Collectively, those analysts predicted, as of July 6, that the S&P 500 would finish this year at 2153. The index closed above that level on Friday, at 2161.74, despite slipping 0.1% after four record closes in a row. Analysts revise their year-end targets throughout the year. In mid-January, the average year-end target was 2198, according to Birinyi Associates.

Markets elsewhere rallied for the week. Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average rose 9.2% over five sessions, its best performance in 6 1/2 years. The Stoxx Europe 600 rose 3.2% in the week. “The market is showing us, if nothing else, its resilience,” said Jason Browne, chief investment officer of FundX Investment Group in San Francisco. Investors began to put money back into riskier assets such as stocks, an encouraging sign to those who had worried about the stream of money leaving equity funds this year. In the seven days to July 13, investors poured a net $7.8 billion into U.S. equity funds, according to data provider Lipper. It was the first weekly inflow since late April.

I could see Brexit having a role here.

• EU Plays Catch-Up on Swaps Collateral Under US Pressure (BBG)

European Union regulators are considering ways to speed the implementation of collateral requirements for derivatives as the bloc’s failure to meet a global deadline threatens to fracture the $493 trillion market. The European Commission said last month it wouldn’t meet a Sept. 1 global deadline. In a draft letter addressed to the main EU regulators, the bloc’s executive arm is now proposing to adapt its plans to “align with the internationally agreed timelines as closely as possible.” Previously, the commission said it would finish EU technical rules on margins for non-centrally cleared over-the-counter derivatives by year-end and have them take effect before mid-2017. That prompted a backlash from regulators in Washington and Tokyo, who said they intended to impose the rules on schedule, while leaving the door open to a delay.

The regulations will apply billions of dollars in collateral demands to swaps traded by the world’s largest banks, including JPMorgan Chase, Barclays and Deutsche Bank. The financial industry has called for global regulators to enforce the requirements at the same time to avoid creating the potential for regulatory arbitrage between jurisdictions. The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which includes regulators from around the world, helped set the international deadlines that start taking effect for the biggest banks in September and ratchet up starting in March 2017. The over-the-counter swap market is estimated at $493 trillion by the Bank for International Settlements. In the undated draft letter seen by Bloomberg, the commission proposed that the requirements would take effect one month after the EU’s technical rules enter into force.

The age of the strongman is upon us. This one takes pensions.

• $35 Billion Pension Bomb Shows Who Really Has Power in Poland (BBG)

It took up less than a minute of a one-hour speech, but led to an unexpectedly busy weekend for the Polish Ministry of Development in Warsaw. At the governing Law & Justice Party’s congress on the first Saturday of this month, leader Jaroslaw Kaczynski spelled out his vision for the country. He mentioned briefly that Poland should do more with the money parked in its retirement funds. At Kaczynski’s ministry of choice for economic policy, senior officials swiftly rounded up colleagues to work through Sunday so that at 8:30 a.m. the next day – before financial markets opened – an overhaul of the $35 billion pension industry could be unveiled. Investment companies were incredulous and the stock market dropped, though it came as little surprise to the people close to the real power in Poland.

Kaczynski, 67, holds no office beyond his role as lawmaker – he’s not the prime minister, president and doesn’t even run a department. His drumbeat of mistrust for both Russia and western Europe, the them-and-us attacks on Poland’s post-communist elite and his courting of the Catholic church give him enough of a devoted following that he needs no title. “Politically, he’s a sort of commander in chief or a first secretary we knew from the times of communism,” said Marek Migalski at Silesian University in Katowice. A former Law & Justice lawmaker in the European Parliament, he was ostracized by the party for criticizing Kaczynski in 2010. “I’d say that for his supporters, he’s even more than Moses. It’s not just a notion that Kaczynski is doing only good things, it’s the conviction that things that are done by Kaczynski are good.”

Anyone ever doubted this?

• EU Commission Has Known for Years about Diesel Manipulation (Spiegel)

Since at least 2010, the European Commission has been in possession of concrete evidence that automobile manufacturers were cheating on emissions values of diesel vehicles, according to a number of internal documents that SPIEGEL ONLINE has obtained. The papers show that emissions cheating had been under discussion for years both within the Commission and the EU member state governments. The documents also show that the German government was informed of a 2012 meeting on the issue. The scandal first hit the headlines in 2015 when it became known that Volkswagen had manipulated the emissions of its diesel vehicles. The records provide a rough chronology of the scandal, which reaches back to the middle of the 2000s.

Back then, European Commission experts noticed an odd phenomenon: Air quality in European cities was improving much more slowly than was to be expected in light of stricter emissions regulations. The Commission charged the Joint Research Centre (JRC) – an organization that carries out studies on behalf of the Commission – with measuring emissions in real-life conditions. To do so, JRC used a portable device known as the Freeway Performance Measurement System (PeMS), which measures the temperature and chemical makeup of emissions in addition to vehicle data such as speed and acceleration. This technology, which was later used to reveal VW emissions manipulation in the United States, was largely developed by the JRC.

JRC launched their PeMS tests in 2007 and quickly discovered that nitrogen oxide emissions from diesel vehicles were much higher under road conditions than in the laboratory. The initial results were published in a journal in 2008 and they came to the attention of the Commission. On Oct. 8, 2010 – roughly three years after the JRC tests – an internal memo noted that it was “well known” that there was a discrepancy between diesel vehicle emissions during the type approval stage (when new vehicle models are approved for use on European roads) and real-world driving conditions. The document also makes the origin of this discrepancy clear: It is the product of “an extended use of certain abatement technologies in diesel vehicles.”

Wow. A feast for the eye and the mind. Don’t miss it.

• Economics Is For Everyone! (Chang)

‘Economics is for everyone’, argues legendary economist Ha-Joon Chang in our latest mind-blowing RSA Animate. This is the video economists don’t want you to see! Chang explains why every single person can and SHOULD get their head around basic economics. He pulls back the curtain on the often mystifying language of derivatives and quantitative easing, and explains how easily economic myths and assumptions become gospel. Arm yourself with some facts, and get involved in discussions about the fundamentals that underpin our day-to-day lives.