Harris&Ewing Preparations for inauguration of Woodrow Wilson 1913

Two big events in September?!

• September Is Looking Likelier for Fed’s First Rate Increase (NY Times)

The Federal Reserve remains on track to raise interest rates later this year, and perhaps as soon as its next policy meeting in mid-September, as economic growth continues to meet its expectations. The Fed issued an upbeat assessment of economic conditions on Wednesday after a two-day meeting of its policy-making committee. While growth remains disappointing by past standards, the Fed said the economy continued to expand at a “moderate” pace, which is driving “solid job gains and declining unemployment.” The statement suggested officials didn’t need to see much more progress before they started to increase their benchmark rate, which they have held near zero since December 2008.

The Fed, which said after the last meeting, in June, of the Federal Open Market Committee that it wanted to see “further improvement” in labor markets, said on Wednesday that “some further improvement” would now suffice. “The addition of the word ‘some’ may appear minor, but the Fed doesn’t add words willy-nilly to the F.O.M.C. statement,” wrote Michael Feroli at JPMorgan Chase. “It leaves the door wide open to a September liftoff, but still retains the optionality to delay hiking if the jobs reports disappoint between now and mid-September.” The decision to keep rates near zero for at least a few more weeks was unanimous, supported by all 10 voting members of the committee. But a number of those officials have said in recent months that they do not think the Fed should wait much longer.

The Fed’s policy committee next meets Sept. 16 and 17. Surveys of economic forecasters show that most expect the Fed to start raising interest rates at that September meeting. But measures of market expectations point to a December liftoff.[..] The Fed has kept its benchmark interest rate near zero as the main element in its campaign to revive economic growth and increase employment after the Great Recession. And it has repeatedly extended that stimulus campaign in the face of disappointing economic news, to avoid raising rates too soon. In recent months, however, officials including Janet L. Yellen, the Fed’s chairwoman, have suggested they are growing more worried about waiting too long. Economic growth has increased after a rough winter, and employment expanded by an average of 208,000 jobs a month during the first half of the year, dropping the unemployment rate to 5.3%.

Number 2.

• SYRIZA To Hold ‘Emergency’ Congress In September (DW)

The SYRIZA party is seen as sliding toward a split prompted by a rebellion by about a quarter of the party’s Left Platform legislators who voted against austerity measures that were part of the conditions agreed on July 13 in Brussels to secure up to €86 billion in new financing. According to analysts the party differences challenge Tsipras’ authority and complicate Greece’s bailout negotiations. It began when a faction of left wing SYRIZA legislators turned against Tsipras when Parliament voted on the bailout, which passed only with support from opposition parties. Thus the party congress that has been proposed by Prime Minister Tsipras is seen as a test of his leadership.

In a televised address to the central committee, Tsipras warned that the government could fall if it was not supported by its leftist deputies. “The first leftist government in Europe after the Second World War is either supported by leftist deputies, or it is brought down by them because it is not considered leftist,” he said. As conflicts arose in the central committee, a meeting was called to attempt to settle those differences over whether Tsipras should have accepted Greece’s third bailout from international creditors. The central committee meeting coincided with the arrival in Athens of the IMF’s head of mission, Delia Velculescu. According to a report in Thursday’s Financial Times, an internal document showed the IMF board had been told that Greece’s levels of debt and past record of slow or non-existent reform disqualify it for a third.

According to the leaked IMF document, the Washington based lender could take months to decide whether it will take part in a fresh bailout. The IMF’s Velculescu was due to join the other international creditors: the EC, the ECB and the European Stability Mechanism. The four institutions are due to meet Friday with Finance Minister Euclid Tsakalotos and Economy Minister Giorgos Stathakis.

..and drag everything down with them..

• China’s Stocks Extend Slump in Worst Monthly Decline Since 2009

China’s stocks fell, with the benchmark index heading for its worst monthly drop in almost six years, as the government struggles to rekindle investor interest amid a $3.5 trillion rout. The Shanghai Composite Index slid 0.8% to 3,677.83 at 1:02 p.m., dragged down by energy and industrial companies. The gauge has tumbled 14% this month, the biggest loss among 93 global benchmark gauges tracked by Bloomberg, as margin traders cashed out and new equity-account openings tumbled amid concern valuations are unsustainable. While unprecedented state intervention spurred a 18% rebound by the Shanghai Composite from its July 8 low, volatility returned on Monday when the gauge plunged 8.5%.

Outstanding margin debt on mainland bourses has fallen about 40% since mid-June, while the number of new stock investors shrank last week to the smallest since the government started releasing figures in May. Individuals account for more than 80% of stock trading in China. “The support measures may have been less effective than what Beijing imagined,” said Bernard Aw, a strategist at IG Asia. The Hang Seng China Enterprises Index of mainland shares in Hong Kong has tumbled 14% this month, poised for its worst loss since September 2011. The gauge rose 0.4% Friday, while the Hang Seng Index advanced 0.4%. The CSI 300 Index added 0.1%. Industrial & Commercial Bank of China has been the biggest drag on the Shanghai Composite this month, sinking 9.9%. China Petroleum & Chemical has tumbled 14%, while Ping An Insurance plunged 18%.

Turnover has fallen as volatility surged. The value of shares traded on the Shanghai exchange on Thursday was 53% below the June 8 peak, while a 100-day measure of price swings on the Shanghai Composite climbed to its highest in six years on Friday. Valuations remain elevated after a 29% drop by the benchmark equity gauge. The median stock on mainland bourses trades at 66 times reported earnings, higher than in any of the world’s 10 largest markets, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. That compares with a multiple of 13 in Hong Kong. “The volatility in A-share markets, which was boosted by the surge in margin financing, has made share price performance deviate from the value of stocks in unpredictable ways,” said June Lui, portfolio manager at LGM Investments. “We have been cautious on investing in A shares.”

“Companies thought that China was the land of opportunity, but it’s not living up to that promise..”

• Corporate Giants Sound Profits Alarm Over China Slowdown (FT)

Some of the world’s largest companies have sounded the alarm about the slowdown in the Chinese economy, warning that weaker growth would hit profits in the second half of the year. Car companies such as PSA Peugeot Citroën, Audi and Ford have slashed growth forecasts while industrial goods groups such as Caterpillar and Siemens have all spoken out on the negative impact of China. The warnings are a sign that China’s weaker growth and its stock market rout this month are creating a headache for global corporates that have long relied heavily on the world’s second-largest economy to drive revenues. Audi and France’s Renault both cited China as they cut their global sales targets on Thursday, with Christian Klingler at Audi parent Volkswagen, predicting “a bumpy road” in the country this year.

Peugeot slashed its growth forecast for China from 7% to 3% while earlier this week Ford predicted the first full-year sales fall for the Chinese car market since 1990. US companies have also been affected. “In Asia, the China market has clearly slowed,” said Akhil Johri, chief financial officer at United Technologies, the US industrial group at the company’s earnings call last week. “Real estate investment, new construction starts and floor space sold are all under pressure.” “Companies thought that China was the land of opportunity, but it’s not living up to that promise,” says Ludovic Subran, chief economist at Euler Hermes. “They realise the business environment is changing for the worse.”

China’s slowdown, which follows years of extraordinary growth, has been particularly startling in recent months, with figures last week showing that the country’s factory activity contracted by the most in 15 months in July. The poor figures coincide with a time of turbulence on the Chinese stock market. The Shanghai Composite shed 8.5% on Monday, its steepest drop since 2007. The fall came despite a string of interventions by Beijing to stem the slide in equities, including a ban on short selling and an interest-rate cut. In the consumer goods sector, brewer Anheuser-Busch InBev said on Thursday that volumes fell 6.5% in China as a result of “poor weather across the country and economic headwinds”. Among industrial goods companies, Schneider Electric, one of the world’s largest electrical equipment makers, reported a 12% fall in first-half profit and cut guidance because of “weak construction and industrial markets” in China.

As predicted here.

• “The Virtuous Emerging Market Cycle Is Turning Vicious” (Albert Edwards)

Investors are right to feel that the recent rout in commodity prices differs from that seen in the second half of last year. Back then there was more of a feeling that the decline in the oil price was just partly a catch-up with the weakness seen in other commodities earlier in the year and partly due to a very sharp rise in the dollar, most notably against the euro. Indeed the excellent Gerard Minack in his Downunder Daily points out that US$ strength and expanding supply have been headwinds over the past four years. But the recent sharp decline in prices has been noteworthy for its breadth: prices have fallen in all major currencies, and across all major commodity groups. This suggests that global growth has slowed.” But why?

One theme that has played out as we expected over the last year has been the rapidly deteriorating balance of payments (BoP) situation of emerging market (EM) countries, as reflected in sharply declining foreign exchange (FX) reserves (the BoP is the sum of the current account balance and private sector capital flows). We like to stress the causal relationship between swings in EM FX reserves and their boom and bust cycle. The 1997 Asian crisis demonstrated that there is no free lunch for EM in fixing a currency at an undervalued exchange rate. After a few years of export-led boom, market forces are set in train to destroy that artificial prosperity. Boom turns into bust as the BoP swings from surplus to deficit. Why?

When an exchange rate is initially set at an undervalued level, surpluses typically result in both the current account (as exports boom) and capital account (as foreign investors pour into the country attracted by fast growth). The resultant BoP surplus means that EM authorities intervene heavily in the FX markets to hold their currency down. We saw that both in the mid-1990s and before and after the 2008 financial crisis. Heavy foreign exchange intervention to hold an EM currency down creates money and is QE in all but name and underpins boom-like conditions on a pro-cyclical basis. Eventually this boom leads to a relative rise in inflation and a chronically rising real exchange rate even though the nominal rate might be fixed.

EM competitiveness is lost and the trade surplus declines or in extremis swings to large deficit. The capital account can also swing to deficit as fixed direct investment flows reverse as EM countries are no longer cost effective locations for plant. Ultimately as the BoP swings to deficit and FX reserves fall, QE goes into reverse, slowing the economy and exacerbating capital flight. As a virtuous EM cycle turns vicious (like now), commodity prices, EM asset prices and currencies come under heavy downward pressure – at which point it is difficult to discern any longer the chicken from the egg. In my view the egg was definitely laid a few years back as EM real exchange rates rose sharply and the rapid rises of FX reserves began to stall.

The MSM sets the tone of the debate by calling refugees ‘migrants’, and by calling SYRIZA and M5S ‘populist’. And no, Matt, Greece did not get to choose between Grexit and austerity, but obliteration and austerity.

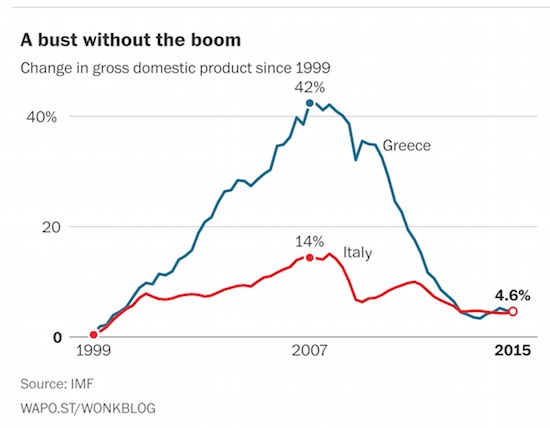

• Italy Is The Most Likely Country To Leave The Euro (WaPo)

What do you call a country that has grown 4.6%—in total—since it joined the euro 16 years ago? Well, probably the one most likely to leave the common currency. Or Italy, for short. It’s hard to say what went wrong with Italy, because nothing ever went right. It grew 4% its first year or so in the euro, but almost not at all in the 15 years since. Now, that’s not to say that it’s been flat the whole time. It hasn’t. It got as much as 14% bigger as it was when it joined the euro, before the 2008 recession and 2011 double-dip erased most of that progress. But unlike, say, Greece, there was never much of a boom. There has only been a bust. The result, though, has been the same. As you can see below, Greece and Italy have both grown a meager 4.6% the past 16 years, although they took drastically different paths to get there.

Part of it is that Italy, as the IMF points out, has real structural problems. It’s hard to start a business, hard to expand one, and hard to fire people, which makes employers wary about hiring them in the first place. That’s led to a small business dystopia, where nobody can achieve the kind of economies of scale that would make them more productive. But, at the same time, Italy had these problems even before it had the euro, and it still managed to grow back then. So part of the problem is the euro itself. It’s too expensive for Italian exporters, and too restrictive for the government that’s had to cut its budget even more than it otherwise would have. This doesn’t make Italy unique—the euro has hurt even the best-run countries—but what does is that Italy’s populists have noticed.

Why is that? Well, more than anything else, the common currency has given Europe a severe case of cognitive dissonance. People hate austerity, but they love the euro even more—they have an emotional attachment to everything it stands for. The problem, though, is that the euro is the reason they have to slash their budgets so much in the first place (at least as long as the ECB will force their banks shut if they don’t). So anti-austerity parties have felt like they have to promise the impossible if they want any hope of gaining power: that they can end the budget cuts without ending the country’s euro membership.

But as Greece’s Syriza party found out, that strategy, if you want to call it one, only gives your people unrealistic expectations and Europe no reason to help you out. The other countries, after all, don’t want to reward what, in their view, is bad budgetary behavior, if not blackmail. And so Greece was all but given an ultimatum: either leave the euro or do even more austerity than it was originally told to do. It chose austerity.

Good piece by Ellen, and certainly not only because she quotes me.

• The Greek Coup: Liquidity as a Weapon of Coercion (Ellen Brown)

In the modern global banking system, all banks need a credit line with the central bank in order to be part of the payments system. Choking off that credit line was a form of blackmail the Greek government couldn’t refuse. Former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis is now being charged with treason for exploring the possibility of an alternative payment system in the event of a Greek exit from the euro. The irony of it all was underscored by Raúl Ilargi Meijer, who opined in a July 27th blog:

The fact that these things were taken into consideration doesn’t mean Syriza was planning a coup . . . . If you want a coup, look instead at the Troika having wrestled control over Greek domestic finances. That’s a coup if you ever saw one. Let’s have an independent commission look into how on earth it is possible that a cabal of unelected movers and shakers gets full control over the entire financial structure of a democratically elected eurozone member government. By all means, let’s see the legal arguments for this.

So how was that coup pulled off? The answer seems to be through extortion. The ECB threatened to turn off the liquidity that all banks – even solvent ones – need to maintain their day-to-day accounting balances. That threat was made good in the run-up to the Greek referendum, when the ECB did turn off the liquidity tap and Greek banks had to close their doors. Businesses were left without supplies and pensioners without food. How was that apparently criminal act justified? Here is the rather tortured reasoning of ECB President Mario Draghi at a press conference on July 16:

There is an article in the [Maastricht] Treaty that says that basically the ECB has the responsibility to promote the smooth functioning of the payment system. But this has to do with . . . the distribution of notes, coins. So not with the provision of liquidity, which actually is regulated by a different provision, in Article 18.1 in the ECB Statute: “In order to achieve the objectives of the ESCB [European System of Central Banks], the ECB and the national central banks may conduct credit operations with credit institutions and other market participants, with lending based on adequate collateral.” This is the Treaty provision. But our operations were not monetary policy operations, but ELA [Emergency Liquidity Assistance] operations, and so they are regulated by a separate agreement, which makes explicit reference to the necessity to have sufficient collateral. So, all in all, liquidity provision has never been unconditional and unlimited.

Don’t forget there is a fourth ‘institution’ that’s party to the talks now, the ESM. It really is a quadriga.

• Greece Crisis Escalates As IMF Witholds Support For New Bail-Out (Telegraph)

Talks over an €86bn bail-out for Greece have been thrown into turmoil after just four days as the IMF said it would have no involvement in the country until it receives explicit assurances over debt sustainability. An IMF official said the fund would withhold financial support unless it has guarantees Greece can carry out a “comprehensive” set of reforms and will be the beneficiary of debt relief from its European creditors. The comments came after the IMF’s executive board was told that the institution could no longer continue pumping more money into the debtor nation, according to a leaked document seen by the Financial Times. The Washington-based Fund has been torn over its involvement in Greece – its largest ever recipient country.

The world’s “lender of last resort’ said it would continue talks with its creditor partners and the Leftist government of Athens, but made it clear the onus of keeping Greece in the eurozone now fell on Europe’s reluctant member states. “There is a need for difficult decisions on both sides… difficult decisions in Greece regarding reforms, and difficult decisions among Greece’s European partners about debt relief,” said the official. “One should not be under the illusion that one side of it can fix the problem.” The delay could last well into next year, forcing the other two-thirds of the Troika – the ECB abd EC – to bear the full costs of keeping Greece afloat.

Athens was forced to request a new IMF rescue package last week after its existing programme – which expired in March 2016 – no longer satisfied IMF conditions to ensure growth and a return to the financial markets for the crisis-ridden economy. IMF managing director Christine Lagarde escalated calls for a “significant debt restructuring” this week. Debt forgiveness has long been the institution’s key condition for extending its involvement in the country after five years of bail-outs. But Europe’s creditor powers – led by Germany – have resisted write-offs, insisting that talks on debt relief can only proceed once the Greek government has satisfied demands to raise taxes, cut pensions spending and privatise assets.

I’m wondering how much of this was preconceived.

• IMF Won’t Help Finance Greece Without Debt Relief (Bloomberg)

The IMF reiterated its unwillingness to provide more financing to Greece without debt relief by euro-member states and further reforms from the Greek government. The Washington-based lender’s management won’t support a new loan program unless Greece’s debt is sustainable in the medium term and the country’s budget is fully financed for 12 months, an IMF official told reporters Thursday on a conference call. The official spoke on condition of anonymity. The IMF will require an explicit, concrete commitment of debt relief from euro-member countries before moving forward with a new loan, the official said. European countries haven’t had detailed discussions with the IMF on a debt restructuring, according to the official.

Greek Finance Minister Euclid Tsakalotos asked the IMF for a new loan in a letter dated July 23 addressed to fund Managing Director Christine Lagarde. Greece has an active loan program with the IMF that expires in March and has about €17 billion that could still be disbursed. In agreeing to a bailout this month that could give Greece as much as €86 billion, most of it financed by euro-zone countries, Greece agreed to seek continued IMF financing beyond March. IMF staff told the fund’s executive board on Wednesday that Greece doesn’t currently qualify for a loan, the Financial Times reported Thursday, citing a confidential summary of the meeting.

And did it know this when Tsipras signed the latest agreement? Moreover, what does that mean legally?

• Will The IMF Throw The Spanner In The Works? (Varoufakis)

“IMF cannot join Greek rescue, board told”… reports Peter Spiegel from Brussels in today’s Financial Times. He adds:“Some Greek officials suspect the IMF and Wolfgang Schäuble, the hardline German finance minister, are determined to scupper a Greek rescue despite this month’s agreement to move forward with a third bailout. In a private teleconference made public this week, Yanis Varoufakis, the former finance minister, said he feared the Greek government would pass new rounds of economic reforms only for the IMF to pull the plug on the programme later this year. “According to its own rules, the IMF cannot participate in any new bailout. I mean, they’ve already violated their rules twice to do so, but I don’t think they will do it a third time,” Mr Varoufakis said. “Dr Schäuble and the IMF have a common interest: they don’t want this deal to go ahead.”

The key issue, of course, is not so much whether the IMF will be part of the deal – a typical fudge could, for instance, be concocted with the IMF providing ‘technical assistance’ to an ESM-only program. The issue is whether the promised debt relief which, astonishingly will be discussed only after the new loan agreement is signed and sealed, will prove adequate – assuming it is granted at all. Or whether, as I very much fear, the debt relief will be too little while the austerity involved proves catastrophically large.

4 different articles by Yanis today; he’s getting very prolific.

• The Lethal Deferral of Greek Debt Restructuring (Varoufakis)

The point of restructuring debt is to reduce the volume of new loans needed to salvage an insolvent entity. Creditors offer debt relief to get more value back and to extend as little new finance to the insolvent entity as possible. Remarkably, Greece’s creditors seem unable to appreciate this sound financial principle. Where Greek debt is concerned, a clear pattern has emerged over the past five years. It remains unbroken to this day. In 2010, Europe and the International Monetary Fund extended loans to the insolvent Greek state equal to 44% of the country’s GDP. The very mention of debt restructuring was considered inadmissible and a cause for ridiculing those of us who dared suggest its inevitability. In 2012, as the debt-to-GDP ratio skyrocketed, Greece’s private creditors were given a significant 34% haircut.

At the same time, however, new loans worth 63% of GDP were added to Greece’s national debt. A few months later, in November, the Eurogroup (comprising eurozone members’ finance ministers) indicated that debt relief would be finalized by December 2014, once the 2012 program was “successfully” completed and the Greek government’s budget had attained a primary surplus (which excludes interest payments). In 2015, however, with the primary surplus achieved, Greece’s creditors refused even to discuss debt relief. For five months, negotiations remained at an impasse, culminating in the July 5 referendum in Greece, in which voters overwhelmingly rejected further austerity, and the Greek government’s subsequent surrender, formalized in the July 12 Euro Summit agreement.

That agreement, which is now the blueprint for Greece’s relationship with the eurozone, perpetuates the five-year-long pattern of placing debt restructuring at the end of a sorry sequence of fiscal tightening, economic contraction, and program failure. Indeed, the sequence of the new “bailout” envisaged in the July 12 agreement predictably begins with the adoption – before the end of the month – of harsh tax measures and medium-term fiscal targets equivalent to another bout of stringent austerity. Then comes a mid-summer negotiation of another large loan, equivalent to 48% of GDP (the debt-to-GDP ratio is already above 180%). Finally, in November, at the earliest, and after the first review of the new program is completed, “the Eurogroup stands ready to consider, if necessary, possible additional measures… aiming at ensuring that gross financing needs remain at a sustainable level.”

Funny story.

• A Most Peculiar Friendship (Varoufakis)

Crises sever old bonds. But they also forge splendid new friendships. Over the past months one such friendship has struck me as a marvellous reflection of the new possibilities that Europe’s crisis has spawned. When I was living in Britain, between 1978 and 1988, Lord (then Norman) Lamont represented everything that I opposed. Even though I appreciated Margaret Thatcher’s candour, her regime stood for everything I resisted. Indeed, there was hardly a demonstration against her government that I failed to join; the pinnacle being the 1984 miners’ strike that engulfed me on a daily basis, in all its bitterness and glory.

For Lord Lamont, a stalwart conservative politician, an investment banker, and long standing Treasury and cabinet minister under both Margaret Thatcher and John Major, my ilk surely represented everything that was objectionable in the youth of the day. And yet since I became minister, and especially after my resignation, Lord Lamont has been steadfast in his support and extremely generous with his counsel. Indeed, I would be honoured if he allowed me to count him as a good friend. Fascinatingly, neither Lord Lamont nor I have changed our political spots much. He remains a solid conservative thinker and politician. And I continue to hold on to my erratic Marxism. Which brings me to the fascinating question: How is such a friendship possible?

The answer is simple: A common commitment to democracy and to the indispensability of Parliament’s sovereignty. Tories like Lord Lamont and lefties of my sort may disagree strongly on society’s ends. But we agree that rules and markets are means to social ends that can only be determined by a sovereign people through a Parliament in which that sovereignty is vested. We may disagree on the functioning, capacity and limits of markets, or even on the precise meaning of freedom in a social context. But we are as one in the conviction that monetary policy cannot de-politicised, not be allowed to determine the limits of a nation’s sovereignty. The notion that a people’s sovereignty ends when insolvency beckons is anathema to both.

Posted this yesterday as a pic, and awkward format. Here’s the text as Varoufakis posted it.

• The Defeat of Europe – my piece in Le Monde Diplomatique (Varoufakis)

Perhaps the most dispiriting experience was to be an eyewitness to the humiliation of the Commission and of the few friendly, well-meaning finance ministers. To be told by good people holding high office in the Commission and in the French government that “the Commission must defer to the Eurogroup’s President”, or that “France is not what it used to be”, made me almost weep. To hear the German finance minister say, on 8th June, in his office, that he had no advice for me on how to prevent an accident that would be tremendously costly for Europe as a whole, disappointed me. By the end of June, we had given ground on most of the troika’s demands, the exception being that we insisted on a mild debt restructure involving no haircuts and smart debt swaps.

On 25th June I attended my penultimate Eurogroup meeting where I was presented with the troika’s ‘take it or leave it’ offer. Having met the troika nine tenths of the way, we were expecting them to move towards us a little, to allow for something resembling an honourable agreement. Instead, they backtracked in relation to their own, previous position (e.g. on VAT). Clearly they were demanding that we capitulate in a manner that demonstrates our humiliation to the whole world, offering us a deal that, even if we had accepted, would destroy what is left of Greece’s social economy. On the following day, Prime Minister Tsipras announced that the troika’s ultimatum would be put to the Greek people in a referendum. A day later, on Friday 27th June, I attended my last Eurogroup meeting.

It was the meeting which put in train the foretold closure of Greece’s banks; a form of punishment for our audacity to consult our people. In that meeting, President Dijsselbloem announced that he was about to convene a second meeting later that evening without me; without Greece being represented. I protested that he cannot, of his own accord, exclude the finance minister of a Eurozone member-state and I asked for legal advice on the matter. After a short break, the advice came from the Secretariat: “The Eurogroup does not exist in European law. It is an informal group and, therefore, there are no written rules to constrain its President.” In my mind, that was the epitaph of the Europe that Adenauer, De Gaulle, Brandt, Giscard, Schmidt, Kohl, Mitterrand etc. had worked towards. Of the Europe that I had always thought of, ever since I was a teenager, as my point of reference, my compass.

It may be the best recipe for blowing up the Union, though.

• The Last Thing the Eurozone Needs Is an Ever Closer Union (Legrain)

‘Fuite en avant’ is a wonderful French expression that is hard to translate into English. Literally, it means “forward flight.” Better approximations include “headlong rush,” “panicky compulsion to exacerbate a crisis,” or even “unconsciously throwing oneself into a dreaded danger.” Faced with Berlin’s power grab to reshape the eurozone along German lines, Paris’s response has been quintessential fuite en avant: proposing even closer ties with Germany in order to try to mitigate the damage done by existing ones. But if a marriage is miserable and divorce is not yet in the cards, might it not be better to have separate bedrooms? To be fair to France’s president, François Hollande, a headlong rush toward greater intimacy has been the default response to previous crises thrown up by European integration, so it is the most common prescription now.

If a fiscal and political union is truly necessary for the eurozone to survive, as many argue, his proposal of a democratically elected eurozone government that would act as a fiscal counterpart to the ECB and – whisper it softly – curb German power may make sense. Italy’s finance minister has suggested something similar. But creating a eurozone government to bridge the economic and political divisions exacerbated by the crisis would be putting the cart before the horse. Or to put it differently, it would be seeking an institutional fix to a much deeper political conflict. Yes, well-functioning common institutions would make Europe’s dysfunctional monetary union work better: Federalism works fine in the United States and elsewhere.

But that is because there is broad political acceptance of those federal institutions’ legitimacy — which, in turn, is because the United States is a nation-state with enough of a sense of shared political community to accept majoritarian democratic rule. Unlike the eurozone. Germany and France sharing a government? Hard to imagine. Germany and Greece? Impossible. Huge numbers of Europeans are unhappy with how the eurozone works. Many don’t trust national elites, let alone European ones. Regrettably, the crisis has revived old stereotypes, such as lazy southerners, and has created new grievances, notably the Troika’s usurping national democracy. Is the solution really to concentrate more powers in Brussels, with France and others giving up even more control over their economic destiny? Is that what French people are clamoring for? Eurozone governance isn’t working, so let’s have more of it. Brilliant.

Even the NYT wakes up to reality.

• Bailout Money Goes to Greece, Only to Flow Out Again (NY Times)

Since 2010 other eurozone countries and the IMF have given Greece about €230 billion in bailout funds. In addition, the ECB has lent about €130 billion to Greek banks. The latest financial aid package is following a similar pattern to the previous ones. Only a fraction of the money, should Greece get it, will go toward healing the economy. Nearly 90% would go toward debts, interest and supporting Greece’s ailing banks. The European Commission has offered to set aside an additional €35 billion development aid package to jump-start the economy. But the funds are difficult to obtain and will become available only in small trickles later in the year. Greeks understandably feel that the latest bailout package is not likely to benefit them very much.

[..] Growth was never the primary consideration when Greece first started receiving bailouts. Back in 2010, political leaders in the eurozone as well as top officials of the IMF were terrified that Greece would default on its debts, imposing huge losses on banks and other investors and threatening a renewed financial crisis. The debt was largely held by Greek and international banks. And Greece, officials feared, could be another Lehman Brothers, the investment bank that collapsed in 2008, setting off a global panic. Forcing banks to take losses on Greek debt “would have had immediate and devastating implications for the Greek banking system, not to mention the broader spillover effects,” said John Lipsky, first deputy managing director of the I.M.F. at the time, during a contentious meeting of the organization’s executive board in May 2010, according to recently disclosed minutes.

To prevent Greece from defaulting on debts, creditors granted Athens a €110 billion bailout in May 2010. But that did not calm fears that other heavily indebted countries might also default. The Greek lifeline was soon followed by bailouts for Ireland and Portugal. When Greece again veered toward a default in summer of 2011, it got a second bailout worth €130 billion, not all of which has been disbursed. Instead of writing off those countries’ debts — standard practice when a country borrows more than it can pay — other eurozone countries and the I.M.F. effectively lent them more money. One of the main goals was to protect European banks that had bought Greek, Irish and Portuguese bonds in hopes of making a tidy profit.

The banks and investors did not escape the pain. In 2012, when Greece was again at risk of default, investors accepted a deal that paid them only about half the face value of their holdings. Much of the aid dispensed to Greece has revolved around banks. Since 2010, Greece has received €227 billion from other eurozone countries and the I.M.F. Of that, €48.2 billion went to replenish the capital of Greek banks. More than €120 billion went to pay debt and interest, and around €35 billion went to commercial banks that had taken losses on Greek debt.

Whether he said it or not, surely no FinMin should have any say in such matters. it’s utterly ridiculous that at least Merkel doesn’t tell him to shut up.

• German FinMin Schäuble Wants To Reduce European Commission Remit (DW)

German Finance Minister Wolfgang Schäuble wants to see the executive body of the EU, the European Commission (EC), lose some of the core fields of responsibility it has previously borne, such as the legal supervision of the EU domestic market, a newspaper reported on Thursday. The “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung” quoted Brussels diplomats as saying that at a meeting of EU finance ministers two weeks ago, Schäuble had called for a quick discussion between EU states about how the EC could fulfil its original functions, which also include monitoring competition within the EU. Schäuble was concerned that the body’s increasing political activities made it incapable of carrying out its function of watching over the correct implementation of the European treaties, according to the report.

The paper said Schäuble has proposed setting up new, politically independent bodies to take over monitoring tasks in view of the EC’s increasing political activity as a “European government.” According to the paper’s report, Schäuble feels that EC president Jean-Claude Juncker exceeded the body’s remit in recent negotiations over new loans for Greece. The German finance minister has often stated that the EC was not empowered to negotiate over Greek loans, but that this was the task of the Eurogroup – made up of eurozone finance ministers – as the representative of European creditors, the paper said. Schäuble attracted much criticism during the recent negotiations on a third bailout for Greece because of his proposal for Greece to temporarily leave the common euro currency.

Juncker has often emphasized that he wants to lead a “political commission.” The German Finance Ministry has dismissed the report, saying that Schäuble merely thought it “important for the Commission to find the right balance between its political function and its role as guardian of the treaties.” This had nothing to do with a “disempowerment of the Commission,” the ministry said.

Having no morals eventually comes back to haunt.

• The IMF’s Euro Crisis (Ngaire Woods)

Over the last few decades, the IMF has learned six important lessons about how to manage government debt crises. In its response to the crisis in Greece, however, each of these lessons has been ignored. The Fund’s participation in the effort to rescue the eurozone may have raised its profile and gained it favor in Europe. But its failure, and the failure of its European shareholders, to adhere to its own best practices may eventually prove to have been a fatal misstep. One key lesson ignored in the Greece debacle is that when a bailout becomes necessary, it should be done once and definitively. The IMF learned this in 1997, when an inadequate bailout of South Korea forced a second round of negotiations. In Greece, the problem is even worse, as the €86 billion ($94 billion) plan now under discussion follows a €110 billion bailout in 2010 and a €130 billion rescue in 2012.

The IMF is, on its own, highly constrained. Its loans are limited to a multiple of a country’s contributions to its capital, and by this measure its loans to Greece are higher than any in its history. Eurozone governments, however, face no such constraints, and were thus free to put in place a program that would have been sustainable. Another lesson that was ignored is not to bail out the banks. The IMF learned this the hard way in the 1980s, when it transferred bad bank loans to Latin American governments onto its own books and those of other governments. In Greece, bad loans issued by French and German banks were moved onto the public books, transferring the exposure not only to European taxpayers, but to the entire membership of the IMF.

The third lesson that the IMF was unable to apply in Greece is that austerity often leads to a vicious cycle, as spending cuts cause the economy to contract far more than it would have otherwise. Because the IMF lends money on a short-term basis, there was an incentive to ignore the effects of austerity in order to arrive at growth projections that imply an ability to repay. Meanwhile, the other eurozone members, seeking to justify less financing, also found it convenient to overlook the calamitous impact of austerity. Fourth, the IMF has learned that reforms are most likely to be implemented when they are few in number and carefully focused. When a country requires assistance, it is tempting for lenders to insist on a long list of reforms. But a crisis-wracked government will struggle to manage multiple demands.

Split it up already.

• Deutsche Bank’s Hard Road Ahead (WSJ)

There’s an old joke in which a tourist asks the way to some pleasant town and gets the answer: “Well, I wouldn’t start from here.” Deutsche Bank’s new leadership should appreciate that more than most. John Cryan, the new chief executive, and the equally new chief financial officer, Marcus Schenck, have one of the biggest jobs among global banks in terms of the cuts needed to both its balance sheet and its cost base. They also, like many other big, global banks must wrestle with a business model in which investors seemingly have lost faith—Deutsche’s stock hasn’t traded above book value since the financial crisis.

Investors will be updated in late October on how these two think they can reshape the bank. Investors will hope for something better than a return on tangible equity of more than 10% in the medium term, which was the miserable target announced before the leadership change in April. One thing investors were told by Mr. Cryan in his first results briefing Thursday is that they shouldn’t have to stump up yet more equity following the bank’s €8 billion rights issue last year. This could prove a challenge to fulfill, though, despite the healthier activity seen in the first half. This pushed Deutsche’s revenues up 20% from a year earlier. Unfortunately, the bank’s costs remain stubbornly high. In the first half, these were equal to 70% of revenue, even excluding hefty legal charges related to the interbank lending rate scandal.

Meanwhile, cutting the bank’s complexity and inefficiencies could take years by Mr. Cryan’s admission. Until this is done, Deutsche will struggle to generate much capital. The bank is actually in a reasonable position on the risk-based capital measure: its core equity tier one capital ratio is 11.4%. However, its leverage ratio is just 3.6% against a target of 5%. And in its largest unit, the investment bank, the leverage ratio is even worse at less than 3%. Changing that will still require a big cut in the investment bank’s assets and liabilities. Mr. Cryan says he will change the bank’s fortunes by weaning it off an overreliance on the balance sheet to generate revenues.

Fine it $100 billion, see what’s left after that.

• Deutsche Bank Didn’t Archive Chats Used by Employees Tied to Libor Probe (WSJ)

A month after reaching a $2.5 billion settlement over interest rate rigging, Deutsche Bank AG told regulators its disclosures may have been incomplete because it accidentally failed to archive electronic chats involving its employees, people familiar with the matter said. The bank is working to recover the records from its systems but might have permanently lost an unknown number of chats dating back to 2005, the people said. The disclosure poses a new regulatory headache for the German lender. Deutsche Bank already has been criticized by regulators for shortcomings in retaining data, including the destruction of hundreds of audiotapes that U.K. regulators said could have been relevant to their investigation into manipulation of the London interbank offered rate, or Libor.

Deutsche Bank disclosed the problem to regulators, including the New York Department of Financial Services, in May, a month after the bank entered into the settlement with a handful of authorities in the U.S. and the U.K., the people familiar with the matter said. “After we discovered this software defect in one of our internal messaging systems, we reported it to our regulators and are presently working with them to rectify it,” the bank said in an emailed statement. “We have been able to recover a majority of the chats via a backup system.” The bank expects the recovery process to be complete in about a month, one of the people familiar with the matter said.

Deutsche Bank so far hasn’t found any communications the bank considers new or relevant to the Libor investigation, one of the people said. The Department of Financial Services, New York state’s top banking regulator, has begun a probe of the incident. It is examining whether potential violations that should have been covered by the Libor settlement weren’t reported because of the error, according to one of the people familiar with the matter. The office is also investigating whether or not the error was intentional and when the bank discovered it.

Think Abe was surprised to see this?

• US Spied On Japan Government, Companies: WikiLeaks (AFP)

The US spied on senior Japanese politicians, its top central banker and major companies including conglomerate Mitsubishi, according to documents released Friday by WikiLeaks, which published a list of at least 35 targets. The latest claim of US National Security Agency espionage follows other documents that showed snooping on allies including Germany and France. There is no specific mention of wiretapping Prime Minister Shinzo Abe but senior members of his government, including Trade Minister Yoichi Miyazawa and Bank of Japan governor Haruhiko Kuroda were targets of the bugging by US intelligence, WikiLeaks said.

Japan is one of Washington’s key allies in the Asia-Pacific region and they regularly consult on defence, economic and trade issues. The spying goes back at least as far as Abe’s brief first term, which began in 2006, WikiLeaks said. Abe swept to power again in late 2012. “The reports demonstrate the depth of US surveillance of the Japanese government, indicating that intelligence was gathered and processed from numerous Japanese government ministries and offices,” it said. “The documents demonstrate intimate knowledge of internal Japanese deliberations” on trade issues, nuclear and climate change policy, among others, it added.

Europe has no morals.

• Europe Could Solve The Migrant Crisis – If It Wanted (Guardian)

Refugees from many countries – not just Sudan but Syria, Eritrea, Afghanistan and beyond – are taking clandestine journeys across Europe in search of a country that will give them the chance to rebuild their lives. Living in Britain and watching what unfolds in Calais – such as the revelation that in recent days there have been 1,500 attempts by migrants to enter the Channel tunnel – it can seem as if they’re all heading here, but in reality Britain ranks mid-table in the proportion of asylum claims it receives relative to population. The number of refugees at Calais has grown because the number of refugees in Europe as a whole has grown. For the most part, their journeys pass unseen, until they hit a barrier – the English Channel; the lines of police at Ventimiglia on the Italy-France border; the forests of Macedonia – that creates a bottleneck and leads to scenes of destitution and chaos.

The political rhetoric that surrounds these migrants makes it harder to understand why they take such journeys. Often when government ministers are called on to comment, they will try to make a distinction between refugees (good) and “economic migrants” (bad). But a refugee needs to think about more than mere survival – like the rest of us, they’re still faced with the question of how to live. What they find when they reach Europe is a system best described as a “lottery”. In theory the EU has a common asylum system; in reality it varies hugely, with different countries more or less likely to accept different nationalities and with provisions for asylum seekers ranging from decent homes and training to support integration in some countries, to tent camps or detention centres, or being left to starve on the street, in others.

Countries that bear the brunt of new waves of migration, such as Italy, Bulgaria or Greece, find little solidarity from their richer neighbours. The EU spends far more on surveillance and deterrence than on improving reception conditions. For as long as these inequalities continue, refugees will keep on moving. This is a crisis of politics as much as it is one of migration, and I think it will develop in one of two ways. Either Europe will continue to militarise its borders and squabble over resettlement quotas of refugees as if they were toxic waste; or we will find the courage and leadership to create a just asylum system where member states pull together to ensure that refugees are offered a basic standard of living wherever they arrive.

The first option, though alluring to many, will only intensify the chaos it’s supposed to protect us from: we put up a fence at Greece’s land border with Turkey, so refugees take to the Mediterranean instead. Britain and France accuse each other of being a soft touch on asylum seekers, so they allow the situation in Calais to fester. For as long as refugees are treated as a burden, they will be the target of racism and violence.

I repeat: the MSM sets the tone of the debate by calling refugees ‘migrants’, and by calling SYRIZA and M5S ‘populist’.

• Why The Language We Use To Talk About Refugees Matters So Much (WaPo)

In an interview with British news station ITV on Thursday, David Cameron told viewers that the French port of Calais was safe and secure, despite a “swarm” of migrants trying to gain access to Britain. Rival politicians soon rushed to criticize the British prime minister’s language: Even Nigel Farage, leader of the anti-immigration UKIP party, jumped in to say he was not “seeking to use language like that” (though he has in the past). Cameron clearly chose his words poorly. As Lisa Doyle, head of advocacy for the Refugee Council puts it, the use of the word swarm was “dehumanizing” – migrants are not insects. It was also badly timed, coming as France deployed riot police to Calais after a Sudanese man became the ninth person in less than two months to die while trying to enter the Channel Tunnel, an underground train line that runs from France to Britain.

Much of the outrage over the British leader’s comments misses an important point, however: Cameron is far from alone when it comes to troubling use of language to describe the world’s current migration crisis. Language is inherently political, and the language used to describe migrants and refugees is politicized. The way we talk about migrants in turn influences the way we deal with them, with sometimes worrying consequences. Consider even the most basic elements of the language about migration. Writing in the Guardian earlier this year, Mawuna Remarque Koutonin asked why white people were often referred to as expatriates. “Top African professionals going to work in Europe are not considered expats,” Koutonin wrote. “They are immigrants.” [..]

There are worries that even “migrant,” perhaps the broadest and most neutral term we have, could become politicized. Trilling pointed out that Katie Hopkins, a controversial British writer and public figure, likened migrants to “cockroaches” in a column published in the Sun. “As both government policy and political rhetoric casts these people as undesirables — a threat to security; a criminal element; a drain on resources — the word used to describe them takes on a new, negative meaning,” Trilling says. Words such as “swarm” or “invasion” can also have implications just as negative when used in connection to refugees. James Hathaway at the University of Michigan Law School, says that these words are “clearly meant to instill fear.” That’s dangerous because the situation in Calais is already inflamed and full of fear: British tabloids are even calling for Cameron to send in the army, as if the migrants represented a foreign power preparing to invade.