NPC Daredevil John “Jammie” Reynolds, Washington DC 1917

“..it appears that the Commission is keen to put in place a procedure for countries to leave the EU..” Wait, Schäuble is not in the Commission.

• Schäuble Was Ready To Give Greece €50 Billion To Quit The Euro (HeardinEurope)

German Minister of Finance Wolfgang Schäuble was prepared “to give Greece €50 billion” had Yanis Varoufakis, his Greek counterpart at the time, agreed to his country leaving the eurozone, a high level source who recently spoke to Schäuble has revealed. The German minister was described by the source like “a true European” who had nothing against Greece, but favoured harsh medicine for a good cause. Schäuble was reported to assume that the leftist Syriza government would favour leaving the eurozone, a move consistent with its ideology. And he was prepared to put money on the table to encourage it to take this step. Schäuble was quoted as asking how much Greece wants to leave the euro by France’s Mediapart.

This is said to taken place before the 5 July referendum, in which a vast majority of Greeks rejected the international creditors’ proposals. But according to the information obtained by Heard in Europe, Schäuble had in mind a concrete figure – €50 billion – had Syriza opted for Grexit. Schäuble apparently didn’t say where the money would come from. Part of such a package could be sourced from the €35 billion of EU money due to Greece until 2020, plus ECB profits from Greek debt sovereign bonds due to Athens. Had Greece opted for a Grexit, more than €300 billion of its debt would be lost to creditors, but €50 billion of fresh money would come handy to the Syriza government to build a new financial system.

Under the bailouts, billions are disbursed to Greece, but the money goes mainly for servicing debt. Regardless of his party’s ideology, at the extraordinary Eurozone summit on 12 July, Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras chose to honour the wishes of the majority of Greeks, who want to keep the euro. Tsipras’ decision was even more surprising given the creditor’s conditions, which our source described as “much, much more brutal compared to any country historically speaking”.

Schäuble is known to be in favour of a five-year timeout of Greece from the eurozone. The idea was rejected at the recent Eurozone summit, but it appears that the Commission is keen to put in place a procedure for countries to leave the EU, similar to the enlargement negotiations, Heard in Europe was told. According to this logic, Greece or the UK, or any other country for that matter, would receive EU support if it leaves the family in an orderly way. And the exit procedure would be accompanied by benchmarks, like the accession path. The money Schäuble was prepared to give Greece could be seen as a precursor to such support, similar to pre-accession financing.

The ECB pays itself.

• Greece’s Real Crisis Deadline Arrives With ECB Debt to Pay (Bloomberg)

Greece has reached the deadline it couldn’t afford to miss, for a bill it can finally afford to pay. Monday is the day the country must reimburse the ECB €4.2 billion, including interest, as bonds bought during its last debt crisis mature. The impending reckoning may have been the factor that eventually forced Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras on July 13 to accept the austerity he and his electorate had previously rejected, in return for the funds needed to keep his nation from default. As Greece blew past multiple political and financial supposed end-dates over the past five months, July 20 always remained make-or-break. EU law bans the ECB from financing governments, meaning a default would probably require it to pull support from Greek lenders, leaving an exit from the single currency all but assured.

“The issue of repayment to the ECB was pivotal, because failure to make the payment would have had a knock-on impact on the ECB’s willingness to continue providing Emergency Liquidity Assistance to the Greek banks,” said Ken Wattret at BNP Paribas in London. “As the realization dawned that Greece was facing a very disorderly, painful exit from the monetary union, the government stepped back from the brink.” While Greece should now have the funds to make the payment, politicians cut it fine. Euro-area leaders agreed on a bailout package worth as much as €86 billion in an overnight summit that ended last Monday. The Greek parliament approved the austerity measures linked to the aid in the early hours of Thursday morning, and the currency bloc signed off on €7 billion of bridge financing the next day.

ECB President Mario Draghi signaled his approval on Thursday by persuading his Governing Council to increase the ELA that is keeping Greek lenders afloat. Banks will reopen for basic services on Monday, three weeks after they were shut to prevent their collapse. In a press conference after the ECB’s decision on ELA, Draghi said he was confident his institution would get its money back on its Greek bonds. “All my evidence and information leads me to say we will be repaid,” he said in Frankfurt. The idea that Greece might default “is off the table,” he said. The ECB hasn’t said if Greece is expected to pay its debt by a specific time.

Nothing much changes, but perhaps the feeling will help a little.

• Greek Banks to Open Monday as Tsipras Prepares for Another Vote (Bloomberg)

Greek banks reopen Monday three weeks after they were shut down to prevent their collapse, as Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras prepares for a second parliamentary vote crucial to securing a bailout. Greeks will regain access to some basic bank services, including the ability to deposit checks and access safe deposit boxes. Although customers will continue to face restrictions on cash withdrawals, the daily limit of €60 will be replaced by a cumulative maximum of €420 a week. The Athens Stock Exchange, which had also been closed during the month-long confrontation between Greece and its creditors, is expected to reopen, as trading was suspended only until the bank holiday ended.

Tsipras is seeking discussions with euro-zone governments on a third bailout after Greek lawmakers went along with their demands for more economic overhauls. Hours after the vote early Thursday, the European Central Bank approved emergency financing for the country’s lenders. The EU followed on Friday with €7 billion bridge loan to keep the country afloat during negotiations on a three-year rescue program worth as much as €86 billion. The loan will help cover a €3.5 billion payment to the ECB that falls due Monday. The Greek government still faces a parliamentary vote Wednesday on a second package of prerequisites for further financial assistance, including tax increases on farmers. Last week’s vote prompted some members of the Syriza party to rebel, forcing Tsipras to reshuffle his cabinet on Friday.

And Italy’s, and Spain’s, and Ireland’s, and…

• Portugal’s Debts Are (Also) Unsustainable (Tavares)

Everyone seems to be focusing on Greece these days – a country so indebted that it needs even more loans to repay just a fraction of its gigantic credits. Clearly this is unsustainable and something has to give. Even the IMF agrees. But what about the other Southern European countries? Actually, Portugal’s financial situation is looking particularly shaky, and any hiccups could have serious cross-border repercussions from Madrid all the way to Berlin. The prevailing narrative is that Portugal has been a star pupil compared to Greece, with austerity delivering much better results:

• The government, a coalition of a center party and center-right party that together have held the majority of parliamentary seats since the 2011 election, pretty much followed all the major guidelines demanded by its creditors (the famous “Troika”) pursuant to the 2010 bailout, and was even praised for it.

• Exports have performed exceedingly well given everything that was going on domestically and abroad; the managers of small and medium enterprises in Portugal are true heroes, operating in difficult conditions and with limited access to credit.

• Portugal has recently become a darling of international real estate investors and tourists.

• The country’s citizens have stoically endured a range of tough austerity measures with surprisingly little social disruption.So it is understandable that hopes for Portugal’s future are much rosier than in Greece… AND YET ITS FINANCIAL SITUATION IS ALSO UNSUSTAINABLE! We realize that this is quite a bold statement. So to support our argument we will use some simple math to show where government finances stand after five years of austerity. The Bank of Portugal (“BdP”), Portugal’s central bank, publishes debt statistics of key sectors in the economy on a quarterly basis. As of March 2015, non-financial public sector debt stood at €288 billion, or 166% of GDP. You may think that there’s something odd right there because you are used to hearing that the Portuguese government “only” owes 130% of its GDP. That’s because the media generally uses Maastricht treaty calculations, not the total amount that the government owes as a whole (which includes public companies, for instance). But what’s 36 %age points of GDP among friends?

OK, let’s do some math: We start by dividing €288 billion by 166% to find out what nominal GDP the BdP used in its calculation: about €174 billion; Next, let’s assume that the cost of debt on all that government debt is only 1%. In this case, the annual interest expense for the government should be 1% x €2.88 billion, or €2.88 billion. We know that this is very low as the actual interest expense in 2014 was almost €7 billion (and likely not all of it, but government accounts can get quite murky); Then we assume that Portugal’s nominal GDP grows at 1%, which is not stellar but certainly better than recent years – from December 2011 to December 2014, the average nominal growth rate was actually -0.6% (BdP figures). So that’s 1% x €174 billion, or €1.74 billion;

Finally, we compare the assumed interest costs with the nominal GDP growth: €2.88 billion vs €1.74 billion. See what we are getting at here? USING FAIRLY OPTIMISTIC ASSUMPTIONS, THE PORTUGUESE ECONOMY IS UNABLE TO GROW ENOUGH TO COVER THE INTEREST ON ITS GOVERNMENT DEBTS, LET ALONE AFFORD ANY PRINCIPAL REPAYMENTS!

If Tsipras implements all austerity measures, it’s impossible for the economy to grow.

• Grexit Remains The Likely Outcome Of This Sorry Process (Münchau)

Alexis Tsipras should never have hired Yanis Varoufakis as his finance minister. Or he should have listened to him, and kept him on. But instead the Greek prime minister chose the worst of all options. He followed Mr Varoufakis’ advice of rejecting the offer of the creditors — until last week. But having done this, Mr Tsipras committed a critical error by rejecting Mr Varoufakis’ plan B for the moment when the country’s banks closed down: the immediate introduction of a parallel currency — IOUs issues by the Greek state but denominated in euros. A parallel currency would have allowed the Greeks to pay for their daily transactions when cash withdrawals were limited to €60 a day. A total economic collapse would have been avoided. But Mr Tsipras did not go for this, or indeed any other plan B.

Instead he capitulated. At that point, he was no longer even in a position to choose a Grexit — a Greek exit from the eurozone. The economic precondition for a smooth departure would have been a primary surplus — before debt service — and an equivalent surplus in the private sector. Greece has no foreign exchange reserves. If the Greeks were to reintroduce the drachma, they would have had to pay for all of their imports with the foreign exchange earnings of their exports. These minimum preconditions were in place in March but not in July. So, like his predecessors, Mr Tsipras ended up with another very lousy bailout deal. And this one suffers from the same fundamental flaws as its predecessors. This leads me to conclude that Grexit remains the most likely ultimate outcome after all.

There are three principal ways in which this can happen. The first is that a deal is simply not concluded. All that was agreed last week is for negotiations to start, plus some interim financing. A deal might fail because principal participants themselves are sceptical. Wolfgang Schäuble, the German finance minister, says he will keep up his offer of a Grexit in his drawer, just in case the negotiations fail. Mr Tsipras denounced the agreement on several occasions last week. And the International Monetary Fund is telling us that the numbers do not add up, and that it will not sign unless the European creditors agree to debt relief. The Germans refuse any discussion on this subject, citing some trumped-up rules according to which eurozone countries are not allowed to default.

This is legal hogwash, but I suppose the purpose is to describe new red lines in the negotiations. My hunch is that they will ultimately fudge a deal, but that will come — as it always does — with overwhelming collateral damage: less debt relief than needed, and more austerity than Greece can bear. A more likely Grexit scenario is that a programme is agreed and then fails. The Athens government may implement all the measures the creditors demand, but the economy fails to recover and debt targets remain elusive. Mr Tsipras already agreed last week that if this situation arose, he would pile on more austerity. So, unless the economy behaves in future in a very different way from the way it behaved in the past, it will remain trapped in a vicious circle for many years to come.

“My money is on exit one way or another.”

• Krugman’s Money Is On A Grexit (CNN)

Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman says Greece’s hard times are far from over – and a Grexit is not out of the question. Eurozone leaders are set to offer new bailout terms for the deeply-indebted Greeks this week. And the country’s banks will also reopen on Monday. Krugman, however, is not convinced the situation in Greece is any less concerning. “My guess is either in the end they will get this sort of enormous debt relief…or they will have to exit,” Krugman told CNN’s Fareed Zakari Sunday. “My money is on exit one way or another.”

And Krugman agreed with some other economists who have said a Grexit shouldn’t be underestimated. Even if forgiving the country’s debt does not lead to “Lehman-like” bank failures, it would affect the stability of the Eurozone. “If Greece exits and then starts to recover, which it probably would, that would be, in a way, encouragement for other political movements to challenge the euro,” Krugman said. “This is not trivial.”

Not a balanced assessment in any sense, but she hits some valid points.

• Why Austerity Is Not a Sound Economic Policy (Forbes)

Austerity is a dubious measure that creditors, such as the IMF like to enforce on poor and politically weak countries aiming to get their money back faster. Unfortunately, austerity creates zombie economies which may have low debt, but unfortunately also end up with low prosperity. Bulgaria, for example is a country that Madam Merkel praised as ”disciplined” with very little government debt that has been able to implement austerity policies effectively. Yet, Bulgaria has the lowest GDP per capita in the EU and remains one of the poorest economies in Europe with little prospects for growth. It is not surprising then that Greece refuses to play ball. The restructuring discussion would have been far more appealing to the Greeks and far more believable if more emphasis was paid to creative ideas of how to jumpstart the Greek economy.

Young and unemployed, the Greeks are not willing to hear about austerity, but would love to hear about how to get a job. At the latest GAIM Conference in Monaco, I participated in a simulation of the Greek crisis. Some of my colleagues suggested interesting ideas focused on Greek economic growth ranging from a Russian natural gas pipeline going through Greece, to Germany relocating manufacturing to Greece and Greeks providing cheap labor, to a free economic zone in the Mediterranean with an infusion of Chinese capital. While each idea may or may not be viable, what was more striking to me is that rarely if ever in the real Greek economic and political debate, do I hear much about stimulating growth and productivity.

Secondly, in addition to economic growth, an innovative approach to debt restructuring is needed not only for Greece but also as a precedent for the world. The global debt including government, corporate and household debt, currently stands at $200 trillion with $57 trillion added since 2007. Current debt levels are likely unsustainable and unlikely to be repaid not just in Greece. A combination of currency devaluation, significant debt forgiveness and creation of new debt instruments that act more like equity and link to GDP growth, for example, will better align incentives between the creditors and the borrowers and ultimately could lead to faster economic recoveries.

Referring to the Greek plan or lack there off, Ian Bremmer, president of Eurasia Group, a political-risk consulting firm said: “It’s clearly a Band-Aid solution. I’d love to say we’ll be back here in a year or two. It’s more likely to be a few months.” I could not agree more with Mr. Bremmer. Much more is needed than bridge loans and austerity.

“There was clearly a need to punish both the Syriza-led government and the Greek voters for daring to protest, by forcing upon them the most appalling and humiliating terms that have been seen in a non-war situation for a European nation..”

• The Failed Project of Europe (Jayati Ghosh)

There is a stereotypical image of an abusive husband, who batters his wife and then beats her even more mercilessly if she dares to protest. It is self-evident that such violent behaviour reflects a failed relationship, one that is unlikely to be resolved through superficial bandaging of wounds. And it is usually stomach-churningly hard to watch such bullies in action, or even read about them. Much of the world has been watching the negotiations in Europe over the fate of Greece in the eurozone with the same sickening sense of horror and disbelief, as leaders of Germany and some other countries behave in similar fashion. The extent of the aggression, the deeply punitive conditionalities being imposed as terms of a still ungenerous bailout and the terrible humiliation and pain being wrought upon the Greek people are hard to explain in purely economic or even political terms.

Instead, all this seems to reflect some deep, visceral anger that has been awakened by the sheer effrontery of a government of a small state that dared to consult its people rather than immediately bowing to the desires of the leaders of larger countries and the unelected technocrats who serve them. There was also anger directed at the people themselves, who dared to vote in a referendum against the terms of a bailout package that offered them only more austerity, less hope and continued pain in the foreseeable future, just so that their country can continue to pay the foreign debts that everyone (even the IMF!) knows simply cannot be paid. The response went beyond completely ignoring the will of the Greek people as expressed in the referendum, to insist on pushing even worse conditions on them for their resistance.

There was clearly a need to punish both the Syriza-led government and the Greek voters for daring to protest, by forcing upon them the most appalling and humiliating terms that have been seen in a non-war situation for a European nation, for the increasingly dubious advantage of staying within the eurozone. Greece will become an economic protectorate, indeed little more than a colony of Germany within the eurozone. It will have no control over its fiscal policies, forced to sell valuable public assets that amount to more than a third of annual national income just to keep trying to pay its creditors. It will have to reverse decisions made in the recent past to preserve some public employment such as of cleaning and sanitation workers and security guards, whom it will now have to fire again, and will have to cut pensions of elderly people who have already seen their pensions fall by 40%.

It will have to increase indirect taxes that will hit the poor most. It will have to accept the constant presence of the external rulers, in the form of an IMF team that will monitor the budget and the activities of the Greek government, who are not any more to be trusted by the European leaders. Since the troika has thus far not been able to push Syriza out of power, they are now seeking the alternative of a much weakened party in government (soon no doubt to become a “government of national unity” with the support of centrist and right wing MPs) under the direct political control of the (mostly unelected) European bosses.

The Greek banking system was bled to death intentionally.

• The Great Greek Bank Drama, Act II: The Heist (Coppola)

Back in the autumn of 2014, the ECB & EBA conducted stress tests on European banks, including all four of Greece’s large banks (which together make up about 90% of its banking sector). The Greek banks at that time passed the stress tests and were deemed solvent. They are now supervised not by Greek regulatory bodies, but directly by the ECB under the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM). Yet now, eight months later, sufficient damage has apparently been done to Greece’s banks to render them collectively insolvent. What on earth has gone wrong? Greece’s banks have suffered a continual deposit drain since the beginning of the year. This is how they became dependent on emergency liquidity assistance (ELA) funding from the Bank of Greece.

But liquidity shortfalls do not cause insolvency unless they are covered by means of asset fire sales. In this case, the liquidity drain was until 28th June covered by ELA. Collateral has to be pledged for ELA funding, and Greek banks consequently found their balance sheets becoming more and more encumbered. To make matters worse, the ECB recently increased collateral haircuts for Greek banks. Now the banks are reopening, it is not clear how much collateral they have left for ELA funding. Whether the ECB will relax collateral requirements to allow a wider range of assets to be pledged remains to be seen. It is probably conditional on good behaviour by the Greek sovereign. But it is not the funding side of Greek banks that is the real problem. It is the asset base.

Greece went into recession in Q4 2014 (yes, BEFORE Syriza came to power). Since then, there has been a considerable fall in output caused mainly by lack of confidence. On top of this, the Greek sovereign has been running substantial primary surpluses all year in order to maintain payments to creditors in the absence of bailout funding. It has done this not by collecting more taxes but by a considerable squeeze on public spending: this has mainly taken the form of delaying payments to the private sector. Additionally, the private sector itself has cut back spending and investment. The result is that real incomes have tumbled, unemployment has risen and loan defaults have increased. Non-performing loans in the Greek banking sector were already high at the beginning of the year but are now believed to have risen substantially. This is the principal cause of the possible insolvency of Greek banks.

All young people are victims.

• Greek Austerity May Be An Economic Tale But Children Are The Human Cost (Conv.)

Many perspectives have been shared about the social and economic repercussions that the third EU bailout proposal for Greece may have. The impact of these tough austerity measures is yet to unfold for the country, for the other southern states, or indeed Europe as a whole. But moving beyond a purely economic lens, there is already evidence about the extent of deprivation and youth unemployment of more than 50% during the past five years of the first and second bailout programmes, meaning that the likely effects of the third are easier to predict, at least for this generation. The links between poverty and a range of risk factors for child mental health problems and related outcomes is well established.

Nevertheless, the reality hit home a few weeks ago when I joined the Children’s SOS Villages in Greece in training their prospective new carers, or “mothers” and “aunts” as they are widely called. These carers work in a similar way to foster carers and residential care staff in other welfare systems. The villages were established in Austria after World War II to care for orphan children and since then their model has successfully spread across more than 120 countries. Their model may slightly vary, but their target groups are typically children without parents, for a range of reasons, or those who have been abused and/or neglected. Consequently, it came as a surprise to realise the extent of child abandonment (neglect, an inability to care for them or even asking social services to look after them) for predominantly financial reasons since the beginning of the Greek crisis.

The organisation has responded by diversifying its remit in Greece. In the absence of an increasingly stretched health and social care sector, they have now extended their services beyond the traditional villages to support, relieve and prevent abuse and neglect, running eight social centres in Greece’s major cities to help keep families together. A 2014 UNICEF report said that child poverty in Greece had almost doubled from 23% in 2008 to 40.5% in 2012, with migrant children particularly vulnerable. It found average family incomes were at 1998 levels, and 18% of households with children unable to afford a meal with meat, chicken, fish or a vegetable equivalent every second day.

At least with Coke, the people got to vote.

• The Euro – The ‘New’ Coke Of Currencies? (Guardian)

The date 23 April 1985 was a momentous day in the life of the Coca-Cola corporation. For years, the company had been planning a new drink to see off the challenge from Pepsi. There was no expense spared for Project Kansas. “New” Coke (as it was dubbed) bombed. The company responded with alacrity. It didn’t say consumers were wrong. It didn’t say that given time New Coke would be a success. It didn’t plough on simply because it had invested heavily in Project Kansas. Instead, it recognised that there was only one option: to go back to the traditional formula. This returned to the shelves on 11 July 1985, within three months of “New” Coke’s launch. There is a lesson here for both businesses and policymakers – and European policymakers in particular.

Sixteen years after its launch, it should be clear even to its most die-hard supporters that the euro is New Coke. European politicians took a formula that was working and messed around with it. They changed the ingredients that made the EU a success, thinking it would be an improvement. Coca-Cola thought New Coke would see off the challenge from Pepsi. Europe thought the euro would see off the challenge from the US. Both were wrong. The only difference is that Coke quickly saw the writing on the wall, and that Europe still hasn’t. It is not hard to see why the pre-euro European Union was popular. The EU was seen as a symbol of peace and prosperity after a period when the continent had been beset by mass unemployment, poverty, dictatorship and war.

Growth rates were spectacularly high in the 1950s and 1960s, a period when Europe caught up rapidly with the US. Britain’s decision to join what was then the European Economic Community in 1973 was mainly due to the feeling that Germany, France and Italy had found the secret of economic success. Other countries felt the same. They believed access to a bigger market would improve their economic prospects. In the last quarter of the 20th century, output per head in Greece, Portugal, Spain and – most spectacularly – Ireland, rose more rapidly than it did in core countries such as Germany and France. The gap in incomes per head did not entirely disappear but it certainly narrowed. As such, it was no surprise that countries in eastern Europe wanted to join the EU after the collapse of communism: Europe was associated with democracy and prosperity, a winning combination.

Since the birth of the euro, it has been a different story. The crisis in Greece has highlighted the problems that a one-size-fits-all interest rate can cause for countries on the periphery. In the good times, monetary policy is too loose for their needs, leading to asset bubbles, inflationary pressure and the loss of competitiveness. In the bad times, there are no shock absorbers other than wage cuts and austerity. Devaluation of the currency is not possible and there is no system to tio transfer resources from rich to poor parts of the union. Without a common social security system, the result is higher unemployment, rising poverty and political disaffection. What’s less remarked on is that the single currency has not been wonderful for ordinary workers in core Europe either. That’s not just true of Italy, a founder member, where living standards are no higher now than they were in the late 1990s, but also of Germany.

The big wigs had solid reasons to want him out of the way.

• Disgraced Ex-IMF Chief Strauss-Kahn Slams New Greek Deal As ‘Deadly Blow’ (RT)

The former head of the IMF, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, has decried the latest deal reached on a new Greek bailout as “profoundly damaging.” While admitting that the deal removed the risk of a Grexit, he stressed that “the conditions of the agreement, however, are positively alarming for those who still believe in the future of Europe.” “What happened last weekend was for me profoundly damaging, if not a deadly blow,” he wrote in the open letter entitled “To my German friends” published on Saturday. Strauss-Kahn referred to the deal as a “diktat” and accused European leaders of putting ideology and political gains ahead of real problems, and thus risking the integrity of the European Union.

“Political leaders seemed far too savvy to want to seize the opportunity of an ideological victory over a far left government at the expense of fragmenting the Union,” he said, adding that negotiations had ended up in a “crippling situation” due to this. He also accused the creditors of adopting ineffective strategies towards Greece, more intended to “punish,” than to promote the future of Europe. “In counting our billions instead of using them to build, in refusing to accept an albeit obvious loss by constantly postponing any commitment on reducing the debt, in preferring to humiliate a people because they are unable to reform, and putting resentments – however justified – before projects for the future, we are turning our backs on what Europe should be, we are turning our backs on (…) citizen solidarity,” Strauss-Kahn said in his letter.

He also emphasized the necessity of reforming the whole currency union calling it “an imperfect monetary union forged on an ambiguous agreement between France and Germany,” adding that neither Germany nor France had a “true common vision of the Union,” being “trapped in misleading and inconsistent” concepts. He stressed that Europe could not be saved “simply by imposing rules of sound management,” but only by mutual respect built “through democracy and dialogue, through reason, and not by force.” He also cautioned European leaders against taking measures that created division in Europe and being overly dependent on their perceived “friend” – the USA. “An alliance between a few European countries, even led by the most powerful among them, will be subjugated by our friend and ally the United States in the maybe not so distant future,” he said.

A rich culture through the ages.

• The Right -Greek- Poem (New Yorker)

When Greeks want to gesture “No,” they nod: a little upward snap of the head. The confusion that this can produce in visitors has long been an object of amusement for the locals—and the source of rueful anecdotes by tourists who have found themselves inadvertently refusing bellhops or a sweating glass of frappé after a hot afternoon on the Acropolis. Lately, you’d be forgiven for thinking that the Greeks themselves have been having a hard time understanding the difference between “yes” and “no.” On July 5th, at the ostensible encouragement of the Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, an overwhelming majority voted no to punishing new austerity measures in return for continued membership in the euro zone—“a bed of Procrustes,” as The American Interest described the dilemma.

A week later, however—after an escalating struggle between Tsipras’s government and European creditors that the Telegraph compared to “a tragedy from Euripides”—the same electorate was being called upon by Tsipras to say yes to a bailout offer more “draconian” (CNBC) than the last one. “Draconian,” “procrustean,” “Euripides”: however confusing the state of affairs in Athens and Brussels right now, it’s clear that the temptation to invoke the glories of ancient Greece in connection with the current Greek economic crisis is one that journalists have found impossible to resist. Most of the allusions are unlikely to send readers racing to Wikipedia. “ ‘Grexit’ Brinkmanship Is Classic Greek Tragedy,” went one headline, on Breitbart.com. (The article contained a link to the Web page for a Greek-tragedy course at Utah State University.)

Some betray a sentimental high-mindedness about Greece’s position in the history of civilization: “In Greece, A Vote Befitting The Birthplace Of Democracy?” Reuters mused. Of the more substantive attempts to link Greece’s grandiose past to its humbled present, nearly all have focussed on a notorious incident from the Peloponnesian War—the ruinous, three-decade-long conflict between Athens and Sparta. In 416 B.C., the Athenians brutally punished the tiny island state of Melos for trying to preserve its neutrality. In a famous passage of Thucydides’ history of the war, known as the Melian Dialogue, the Athenian representatives blithely tell their Melian counterparts, “The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must,” before killing all the adult males of the city and enslaving the women and children.

Perceived similarities between the Athenians of the fifth century B.C. and today’s Germans have provoked a flurry of think pieces. “What Would Thucydides Say About the Crisis in Greece?” an Op-Ed in the Times asked. Yet, despite the baggy analogizing and the rhetoric about eternal verities, attempts to use Pericles’ Athens to explain Tsipras’s Greece often obscure important differences. “Melos was a neutral state,” the Times Op-Ed tartly observed, “while modern Greece not only joined the European Union but over the years merrily plundered its treasury.”

It’s easy to see where the impulse to conflate “Greek history” with “Classical Greek history” comes from: appeals to Thucydides or Plato can confer authority in real-world decision-making. (In 2001, some conservatives cited the Athenians’ take-no-prisoners rhetoric at Melos to justify the invasion of Afghanistan.) But the presumption that nothing much of interest happened in Greece between the end of the Classical era, in 323 B.C., and the founding of the modern nation, in the early nineteenth century, has long irritated both Greeks and students of Greek history.

Shameful.

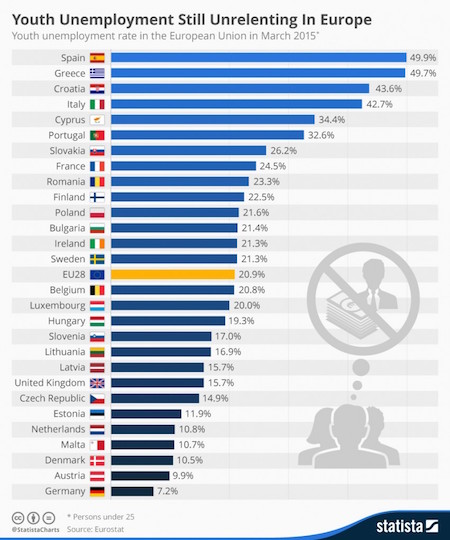

• Youth Unemployment in Europe (OneEurope)

According to this infographic made by Statista (Statista.com) youth unemployment is still a huge problem in many European countries. In March 2015 Spain, Greece, Croatia and Italy had the worst unemployment rate for people under 25 years of age. How could you explain these different%ages of youth unemployment across Europe? What are the main responsible factors for this issue? In which way do you think the European Union should work to solve it?

Let’s see what the IMF has left in its warchest.

• Ukraine Extends Creditor Talks As Threat Of Default Looms (FT)

Ukraine has extended hastily assembled talks with creditors amid predictions that the country could default as early as Friday if an agreement is not reached. Kiev’s desire to avoid the fate of Greece has encouraged both sides to tone down the combative rhetoric that has dogged negotiations over the past three months. However a principal-to-principal meeting held in Washington last week failed to elicit a deal to restructure Ukraine’s $70bn debt burden, although a joint statement declared that progress had been made. Bridging the gap between Ukraine and the international creditors who hold its sovereign debt will not be easy. Following Russia’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimean region and the conflict with pro-Russian separatists in the east that has wrecked its economy, Ukraine’s debt is widely expected to top 100% of GDP this year.

Kiev hopes for a 40% debt writedown on bonds worth a little more than $15bn in order to make the debt sustainable. But a group of four creditors holding around $9bn of Ukrainian bonds, led by US asset manager Franklin Templeton, disagree that a haircut is needed and have put forward an alternative proposal for maturity extensions and coupon reductions. The only concrete example of progress so far has been the suggestion of swapping part of Ukraine’s debt for GDP-linked bonds, which both sides support, and which would offer equity-like returns if the country’s economy outperforms. So far, Ukraine has met all of its debt obligations, including a $75m coupon payment to Russia, and has successfully negotiated maturity extensions on a number of other payments.

However, Goldman Sachs has warned that default looks “likely” in July when a payment of $120m comes due on a Ukrainian government bond.

Good lord: “The halted firms are valued at an average 243 times reported earnings…”

• China Stock Resumptions Dwindle as 20% of Shares Stay Halted (Bloomberg)

A fifth of China’s stock market remains frozen as the number of companies resuming trading slows to a trickle. A total of 576 companies were suspended on mainland exchanges as of the midday break on Monday, equivalent to 20% of total listings, and down from 635 at the close on Friday. The halted firms are valued at an average 243 times reported earnings, compared with 164 times for all companies traded in Shanghai and Shenzhen. The ongoing suspensions are raising doubts about the sustainability of a rebound in Chinese stocks. The Shanghai Composite Index has climbed about 14% from its July 8 low, following a 32% plunge that helped erase almost $4 trillion of value.

The number of companies with trading halts exceeded 1,400, or around 50% of listings, during the height of the rout as the government took increasingly extreme measures to shore up equities. “When half the market becomes illiquid, that was a sign that China had regressed, they’re not willing to accept the ups and downs of a capital market,” Roshan Padamadan, the founder and manager of Luminance Global Fund, said in an interview on Bloomberg Television from Singapore. Researching companies becomes “pointless” when the government allows them to halt trading without reason, he said. The suspended companies have a combined value of 4 trillion yuan ($644 billion), equivalent to about 9% of China’s total market capitalization. The majority of halts were by shares listed on the Shenzhen Composite Index, the benchmark gauge for the smaller of China’s two exchanges.

The trend must be worrying to some. Looks like gold goes the way of other commodities.

• Gold Bulls In Retreat After Spectacular Plunge (CNBC)

Gold got whacked in the Asian trading session on Monday, plunging below $1,100 in for the first time since March 2010, and strategists say the precious metal is only headed lower from here. The precious metal’s latest leg down was reportedly triggered by speculative selling in the Shanghai Gold Exchange, catching investors off guard. “It was down to speculation here, someone taking advantage of the low liquidity environment,” Victor Thianpiriya, commodity strategist at ANZ, told CNBC. “Around 5 tonnes of gold was sold on the Shanghai Gold Exchange within the space of two minutes between 09:29 and 09:30. The daily volume last week was about 25 tonnes,” he noted. Gold slid over 4% to as low as $1,086 an ounce in early trade on Monday, before paring back some losses over the course of the day.

It was down 2.3% at $1,107 at around 12:00 SG/HK time. “It clearly wasn’t driven by fundamentals, because the U.S. dollar didn’t move at that time,” Thianpiriya said. The disappointing performance of the yellow metal, which is down 6.4% on a year-to-date basis, has sent gold bulls into retreat. Jonathan Barratt, chief investment officer at Ayers Alliance, a longtime gold bug, says he’s turned “neutral” on the metal. “As you know I’ve been a bull, [but] I’ve got to go neutral now. Gold’s broken through some very critical areas. From a technical perspective it doesn’t look hot,” said Barratt, who expects price could fall back to $1,100 or lower.

Technical analyst Daryl Guppy also warned of “bearish features” on the gold chart: “There is a higher probability of a future fall below $1,150 and a continuation of the downtrend towards historical support near $980.” With the Federal Reserve’s first rate hike looming and the prospect of a stronger greenback, the odds remained stacked against gold, say analysts. “I think there’s further downside on the price once the dust settles and the focus shifts back to U.S. dollar strength and the interest rate outlook,” said Thianpiriya. “The risk of it hitting $1,050 is clearly elevated.”

Too many bets on too few horses. Both Australia and New Zealand look to get hit hard.

• Commodities Crash Could Turn Australia Into A New Greece (Telegraph)

Last month Gina Rinehart, Australia’s richest woman and matriarch of Perth’s Hancock mining dynasty delivered an unwelcome shock to her workers in Western Australia: accept a possible 10pc pay cut or face the risk of future redundancies. Ms Rinehart, whose family have accumulated vast wealth from iron ore mining, has seen her fortune dwindle since commodity prices began their inexorable slide last year. The Australian mining mogul has seen her estimated wealth collapse to around $11bn (£7bn) from a fortune that was thought to be worth around $30bn just three years ago. This colossal collapse in wealth is symptomatic of the wider economic problem now facing Australia, which for years has been known as the lucky country due to its preponderance in natural resources such as iron ore, coal and gold.

During the boom years of the so-called commodities “super cycle” when China couldn’t buy enough of everything that Australia dug out of the ground, the country’s economy resembled oil-rich Saudi Arabia. While the rest of the world suffered from the aftermath of the global financial crisis, Australia’s economy – closely tied to China – appeared impervious, with full employment and a healthy trade surplus. However, a collapse in iron ore and coal prices coupled with the impact of large international mining companies slashing investment has exposed Australia’s true vulnerability. Just like Saudi Arabia, which is now burning its foreign reserves to compensate for falling oil prices, Australia faces a collapse in export revenue. Recently revised figures for April show that the country’s trade deficit with the rest of the world ballooned to a record A$4.14bn (£2bn).

That gap between the value of exports and imports is expected to increase as the value of Australia’s most important resources reaches new multi-year lows. Iron ore is now trading at around $50 per tonne, compared with a peak of around $180 per tonne achieved in 2011. Thermal coal has also suffered heavy losses, now trading at around $60 per tonne compared with around $150 per tonne four years ago. For an economy which in 2012 depended on resources for 65pc of its total trade in goods and services these dramatic falls in prices are almost impossible to absorb without inflicting wider damage. The drop in foreign currency earnings has seen Australia forced to borrow more in order to maintain government spending.

The respected Australian economist Stephen Koukoulas recently wrote of the dangers that escalating levels of foreign debt could present for future generations. Could a prolonged period of depressed commodity prices even turn Australia into Asia’s version of Greece, with China being its banker of last resort instead of the European Union. Mr Koukoulas points out that by the end of the first quarter this year, Australia’s net foreign debt had climbed to a record $955bn, equal to almost 60pc of gross domestic product. Although this is far behind the likes of Greece, which boasts an unenviable ratio of over 175pc, it is nevertheless unsustainable, especially if it is allowed to widen further.

Long interview. Assange is a clever man.

• Interview With Julian Assange: ‘We Are Drowning In Material’ (Spiegel)

SPIEGEL: Mr. Assange, WikiLeaks is back, publishing documents which prove the United States has been surveilling the French government, publishing Saudi diplomatic cables and posting evidence of the massive surveillance of the German government by US secret services. What are the reasons for this comeback?

Assange: Yes, WikiLeaks has been publishing a lot of material in the last few months. We have been publishing right through, but sometimes it has been material which does not concern the West and the Western media — documents about Syria, for example. But you have to consider that there was, and still is, a conflict with the United States government which started in earnest in 2010 after we began publishing a variety of classified US documents.SPIEGEL: What did this mean for you and for WikiLeaks?

Assange: The result was a series of legal cases, blockades, PR attacks and so on. With a banking blockade, WikiLeaks had been cut off from more than 90% of its finances. The blockade happened in a completely extra judicial manner. We took legal measures against the blockade and we have been victorious in the courts, so people can send us donations again.SPIEGEL: What difficulties did you have to overcome?

Assange: There had been attacks on our technical infrastructure. And our staff had to take a 40% pay cut, but we have been able to keep things together without having to fire anybody, which I am quite proud of. We became a bit like Cuba, working out ways around this blockade. Various groups like Germany’s Wau Holland Foundation collected donations for us during the blockade.SPIEGEL: What did you do with the donations you got?

Assange: They enabled us to pay for new infrastructure, which was needed. I have been publishing about the NSA for almost 20 years now, so I was aware of the NSA and GCHQ mass surveillance. We required a next-generation submission system in order to protect our sources.SPIEGEL: And is it in place now?

Assange: Yes, a few months back we launched a next-generation submission system and also integrated it with our publications.

A city the size of Kansas.

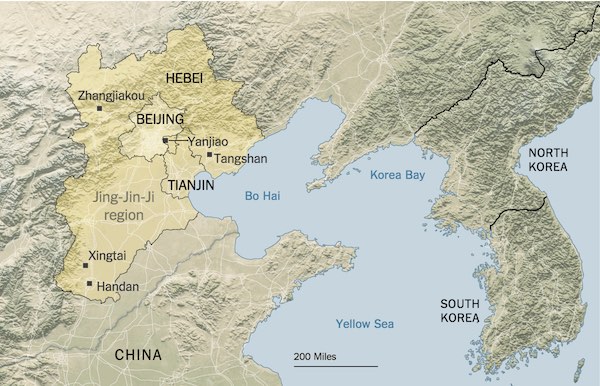

• Beijing To Become Center of Supercity of 130 Million People (NY Times)

For decades, China’s government has tried to limit the size of Beijing, the capital, through draconian residency permits. Now, the government has embarked on an ambitious plan to make Beijing the center of a new supercity of 130 million people. The planned megalopolis, a metropolitan area that would be about six times the size of New York’s, is meant to revamp northern China’s economy and become a laboratory for modern urban growth. “The supercity is the vanguard of economic reform,” said Liu Gang, a professor at Nankai University in Tianjin who advises local governments on regional development. “It reflects the senior leadership’s views on the need for integration, innovation and environmental protection.”

The new region will link the research facilities and creative culture of Beijing with the economic muscle of the port city of Tianjin and the hinterlands of Hebei Province, forcing areas that have never cooperated to work together. This month, the Beijing city government announced its part of the plan, vowing to move much of its bureaucracy, as well as factories and hospitals, to the hinterlands in an effort to offset the city’s strict residency limits, easing congestion, and to spread good-paying jobs into less-developed areas. Jing-Jin-Ji, as the region is called (“Jing” for Beijing, “Jin” for Tianjin and “Ji,” the traditional name for Hebei Province), is meant to help the area catch up to China’s more prosperous economic belts: the Yangtze River Delta around Shanghai and Nanjing in central China, and the Pearl River Delta around Guangzhou and Shenzhen in southern China.

But the new supercity is intended to be different in scope and conception. It would be spread over 82,000 square miles, about the size of Kansas, and hold a population larger than a third of the United States. And unlike metro areas that have grown up organically, Jing-Jin-Ji would be a very deliberate creation. Its centerpiece: a huge expansion of high-speed rail to bring the major cities within an hour’s commute of each other. But some of the new roads and rails are years from completion. For many people, the creation of the supercity so far has meant ever-longer commutes on gridlocked highways to the capital.

“The Southern Ocean, isolated from human pollution, offers us a glimpse into what skies around the world might have looked like in pre-industrial times.”

• Tiny Ocean Phytoplankton are Brightening Up the Sky (Gizmodo)

Phytoplankton may be microscopic, but that doesn’t mean we can’t see them. Just look up: These little critters are brightening up cloudy days around the world. That’s according to research published Friday in the open-access journal Science Advances, which highlights the surprisingly large role microbes in the Southern Ocean play in cloud formation. Tiny phytoplankton can be swept out of their watery homes by gusts of wind. And once airborne, they help encourage water condensation, forming brighter clouds that reflect additional sunlight. “The clouds over the Southern Ocean reflect significantly more sunlight in the summertime than they would without these huge plankton blooms,” said study co-author Daniel McCoy of the University of Washington in a statement.

“In the summer, we get about double the concentration of cloud droplets as we would if it were a biologically dead ocean.” It’s a well-known fact that phytoplankton play a huge role in managing Earth’s climate by drawing down CO2 for photosynthesis every year. The new study suggests another fascinating way that these little critters are shaping our planet—by making it a tad brighter. Averaged over the year, the researchers find that phytoplankton reflect an extra 4 watts of incoming solar radiation per square meter in the Southern Ocean skies. Clouds form when droplets of water condense out of the air around tiny particles— specks of salt, dust, dead organic matter, and even living microorganisms.

Turns out, particle size has a direct impact on cloud brightness: Smaller particles form smaller droplets, creating more surface area within the cloud to reflect back incoming sunlight, which in turn helps keep the Earth’s surface cooler. The researchers stumbled upon cloud-forming microbes somewhat by accident, while they were looking at cloud cover data captured by NASA’s Earth-orbiting MODIS satellite over the Southern Ocean in 2014. The team discovered that Southern Ocean clouds were reflecting more sunlight in the summer, suggesting a greater abundance of small cloud-forming particles. This was a bit weird, because the Southern Ocean surface waters are actually much calmer in the summer and send up less salt spray into to the atmosphere.

The new study took a closer look at what else could be making the clouds more reflective. Using ocean biology models and data on cloud droplet concentrations, the team identified marine life as the likely culprit. Phytoplankton emit gases such as dimethyl sulfide (the stuff that gives the ocean its distinctly sulfurous smell), which, once airborne, can also help condense water droplets. What’s more, summertime plankton blooms form a bubbly scum of tiny organic particles that are easily whipped up into the air. Taken together, these two biological pathways double the number of tiny droplets in Southern Ocean skies during the summer. The Southern Ocean, isolated from human pollution, offers us a glimpse into what skies around the world might have looked like in pre-industrial times. How much of an impact biological cloud seeding has on Earth’s global climate remains to be seen.