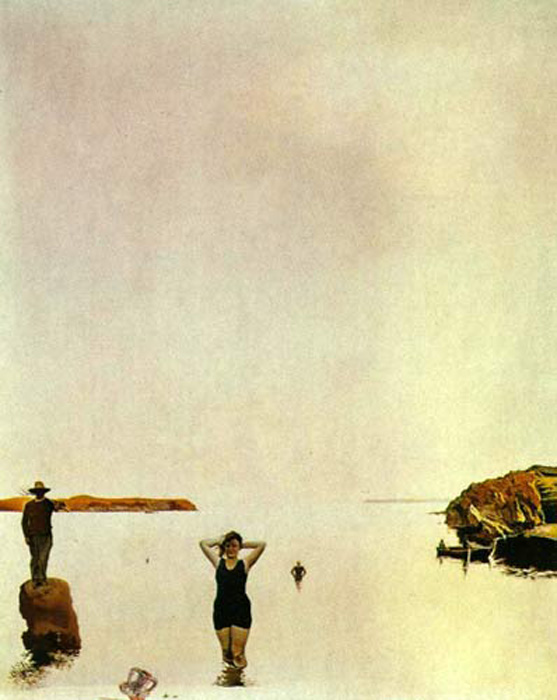

Salvador Dalí White calm 1936

It’s been a while since we last heard from longtime friend of the Automatic Earth Dr. Nelson Lebo III, New Englander living in Wanganui, New Zealand. Nelson has written a fine collection of articles on this site through the years.

Of course I thought, when I first saw this piece in my mailbox, that he would have written about New Zealand’s new prime minister, Labour’s 37-year-young Jacinda Ardern, whose first action in her new job will be to prevent foreigners from buying existing homes in her country. It’ll be interesting to see how she intends to do so while remaining inside the Trans Pacific Partnership -TPP- agreement.

Radio New Zealand has a portrait in which she says ‘I Want The Government … To Bring Kindness Back’. And obviously my first thought was: wait till you meet Donald Trump. But it would be misleading to put the lack of kindness in politics on his shoulders. There’s too much blood on too many hands.

But Nelson didn’t address her this time. I hope he will soon. Instead, and I should have known, he writes about Koyaanisqatsi, life out of balance. When I wrote The Koyaanisqatsi Economy a month ago, he said he had been thinking of the same theme.

Nelson named his article “Pura Vida trumps Koyaanisqatsi”, but I thought his emphasis on volatility is too important to not be the headline. Especially given that volatility in financial markets is at a -near- record low, while it appears blatantly obvious that this not reflect the ‘real world’ at all.

Nelson’s summary of the real world: “..hurricanes, mass shootings, hurricanes, opioid epidemics, hurricanes, people sleeping in cars, hurricanes, rising suicide rates, hurricanes, and children dying from cold damp homes..”

If that doesn’t spell volatility, what does? Forget about financial markets reflecting anything real anymore. Thanks to central banks, markets are fiddling while Rome burns.

Heeeeeere’s … Nelson:

Dr. Nelson Lebo III: Volatility is the new normal – that’s the message I gave a local Rotary Club when I spoke to members four or five years ago. I had been told beforehand the group was “worldly” and specifically instructed in the invitation to challenge them with my presentation. As a weekly columnist in the city’s paper – the Wanganui Chronicle – I was widely known for my positions on wealth inequality, climate change, and debt, as well as a wide range of practical approaches to address these issues.

Around that time it was clear that a post-GFC new normal was functioning worldwide and many writers were using the term. By then The Spirit Level (Pickett & Wilkinson, 2009) had been widely read and widely praised for its documentation of the relationship between wealth and income inequality and social problems. Additionally, peer reviewed research based on decades worth of data had shown there was a quantitatively measurable increase in extreme weather events: more big storms and more big droughts.

I thought my audience would be well on board.

Judging from the response that day, however, the brief I had been given was misguided and most club members were neither expecting nor wanting a presentation that challenged the dominant paradigm of infinite growth without consequences no matter how factual. As a mid-week midday meeting with New Zealand ‘fush ‘n chups’ on the menu the message that the-world-as-you-know-it-has-changed-forever was a bit heavy for people on their lunch break.

The response that day was, of course, perfectly ‘normal’. Almost no adult human seeks out new and different worldviews. On the contrary, we are far more inclined to cling to outdated ones, à la “Make America Great Again” than to acknowledge changing realities.

Social media allows us to reverberate in echo chambers of our own beliefs where we know we’re right because the echo told us so. Social science researchers have told us this for decades. The Internet just makes it worse and more obvious.

I’ve been writing about Trump, doubling-down and the post-truth world for two years now, and if anything I am more certain of the point I’ve been trying to make: most people are irrational. Seems there’s now a Nobel Laureate who has been arguing the same for decades. Behavioral economist Richard Thaler was recently awarded a Nobel for his study of the psychology of economics, which seeks to understand how we are irrational and the impact on traditional economic theories that have failed time and again (think 2008 Global Financial Crisis) because they don’t sufficiently incorporate human factors. (Remember Greenspan’s admission?)

In no way do I intend to single out the Wanganui Rotarians, but rather use this example as illustrative for what my community, nation, and the entire world face: volatility made worse by inertia. In other words, the longer we choose to ignore inconvenient truths the greater will be their negative impacts.

This situation usually manifests in the form of tipping points . Malcolm Gladwell defined a tipping point in his debut book of the same name as “the moment of critical mass, the threshold, the boiling point.” Everything looks fine with the economy and the climate…until it’s not. And by ‘not fine’ we are talking really NOT FINE à la Greece, Puerto Rico, Houston, etc.

Tipping points is volatility on steroids. Brace yourselves.

Well-informed leaders from President Obama to Pope Francis agree the greatest threats facing humanity are climate change and wealth inequality. I’ve written extensively about both for many years yet neither appears to get much traction locally or globally. Our ‘leaders’ ignore these issues at all of our peril because the result of each is increasing volatility in many forms: social, economic, financial, political, and an increasing incidence of extreme weather events.

Volatility is not good for social order, and where I live is a perfect example of the canary in the coalmine: a coastal, river city with high levels of inequality. It’s a tipping point waiting to happen.

Some readers may remember the 1982 film by Godfrey Reggio called Koyaanisqatsi, named using a Hopi term meaning “chaotic life” or “life out of balance.” The film is unnerving, as is much of what comes via news media these days: hurricanes, mass shootings, hurricanes, opioid epidemics, hurricanes, people sleeping in cars, hurricanes, rising suicide rates, hurricanes, and children dying from cold damp homes. And then there’s Myanmar: When Buddhists become the aggressors, you know the world is well and truly out of balance.

Okay, so the world is out of balance. What can be done about it?

Our solution to imbalance, as any regular reader of our blog knows, is called “Eco-Thrifty.” This approach to design and to life is about living better on less. Seems we have good company along these lines in the form of Costa Rica, the small Central American nation that regularly tops the Happy Planet Index published by the New Economics Foundation.

Despite per capita income one quarter that of New Zealand (ranked 38th of 140) and one fifth that of the US (108th of 140) Costa Rica matches many Scandinavian countries in terms of equality, wellbeing, life expectancy and ecological impact.

As Jason Hickel of the Guardian recently put it, “Costa Rica proves that rich countries could theoretically ease their consumption by half or more while maintaining or even increasing their human development indicators.”

“The opposite of growth isn’t austerity, or depression, or voluntary poverty. It is sharing what we already have, so we won’t need to plunder the earth for more.”

Sharing is at the heart of the permaculture ethics, where it is joined by caring for the environment and caring for people. Although we practice permaculture on our farm and in our community, we’re not dogmatic about it. What drives the eco-thrifty bus is resilience accompanied by regeneration.

Resilience, in this context, is the ability to withstand a pulse. It does not happen by accident. It can be designed, built and managed. Resilience only matters 0.0001% of the time, but when it matters it really matters. Resilient homes stand up to earthquakes and hurricanes. Resilient farms stand up to major rain events and extended droughts. Resilient communities withstand economic downturns and ‘natural disasters’.

Regeneration, in this context, is about getting better, stronger, more resilient over time. Regenerative farms grow food while building soil fertility, reducing erosion, storing carbon, managing storm water, and increasing biological diversity. Regenerative communities reduce crime, domestic violence, drug abuse, and suicide rates while keeping wealth and resources circulating locally. They improve quality of life while shrinking energy use, pollution and wealth inequality.

From these perspectives Costa Rica is a good, albeit imperfect, case study. It is, however, about the best example we can find and has the data to show long-term consistently high quality of life.

Pura Vida trumps Koyaanisqatsi.