Edward Meyer School victory garden on First Avenue New York 1944

1990s: “Overnight, tens of millions of workers lost their “iron rice bowls.”

• China’s Coming Mass Layoffs: Past as Prologue? (Diplomat)

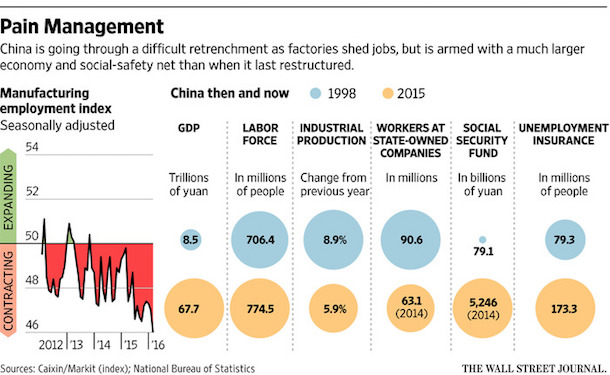

China’s minister for human resources and social security has said that China will lay off 1.8 million workers in the coal and steel sectors, part of an overall plan to reduce overcapacity and streamline state-owned enterprises. Reuters, citing anonymous sources close to China’s leadership, puts the figure much higher, at 5 to 6 million in layoffs over the next two years. Beijing is aware of the risks such massive layoffs pose for social stability, and it’s already moving to control to damage. A Chinese official recently announced that the national government will set aside 100 billion renminbi ($15.3 billion) to help find new employment for those who lose their jobs to the restructuring.

On Wednesday, a spokesperson for the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, which begins its annual session on Friday, assured journalists that the job losses would be “temporary.” At least publicly, Chinese officials are confident that growth in service sector jobs can absorb most of the layoffs from heavy industry. That may seem unlikely, given the sheer number of the coming layoffs, but remember that China has been through this before – and on an even grander scale. In the late 1990s, China drastically restructured its state-owned enterprises, privatizing some and shutting down others. The result: from 1995 to 2002, over 40 million jobs in the state sector were cut, along with nearly 30 million jobs lost in the manufacturing, mining, and utilities sectors.

Although many of these workers were able to pick up jobs in the newly-growing private sector, the societal and cultural shift entailed in the restricting should not be underestimated. Prior to that wave of reforms, state sector employees (the vast majority of China’s workforce) enjoyed the benefits of an “iron rice bowl,” absolute job security along with social benefits (such as healthcare and pensions) provided by the state. Yet as China transitioned to a capitalistic economy – as “socialism with Chinese characteristics” turned out to be – the state sector and its “iron rice bowl” were proving a financial disaster, particularly in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis in the late 1990s.

Chinese blogger Yang Hengjun explained the resulting transition as follows: “The reforms of the 1990s resulted in massive lay-offs. Overnight, tens of millions of workers lost their “iron rice bowls.” There were people who didn’t want to accept it, even those who actively resisted, but the government ruled with an iron fist and eventually the reforms went through. Even today, some of these people have grown old on the edge of poverty. On a certain level, we sacrificed them in exchange for huge reforms to the economic system.”

This is the same situation China faces today: the need for economic restructuring that will inevitably cause economic turmoil for millions of Chinese. China’s reforms in the 1990s had obvious benefits for the Chinese economy; the painful transition toward capitalism help usher in the boom-time of double-digit economic growth during the 2000s. There were consequences as well, particularly noticeable in a wealth gap that has grown at the same breakneck pace as China’s economy. Yet, with all the benefits of hindsight, you’d be hard pressed to find a Chinese official who would argue against the state sector restructuring of the late 1990s.

Ehh..: “..with the right policies, China could survive a deleveraging without too much pain.” That’s true only as long as you don’t understand why deleveraging takes place. You can’t escape it through more debt.

How worrying are China’s debts? They are certainly enormous. At the end of 2015 the country’s total debt reached about 240% of GDP. Private debt, at 200% of GDP, is only slightly lower than it was in Japan at the onset of its lost decades, in 1991, and well above the level in America on the eve of the financial crisis of 2007-08. Sooner or later China will have to reduce this pile of debt. History suggests that the process of deleveraging will be painful, and not just for the Chinese. Explosive growth in Chinese debt is a relatively recent phenomenon. Most of it has accumulated since 2008, when the government began pumping credit through the economy to keep it growing as the rest of the world slumped. Chinese companies are responsible for most of the borrowing. The biggest debtors are large state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which responded eagerly to the government’s nudge to spend.

The borrowing binge is still in full swing. In January banks extended $385 billion (3.5% of GDP) in new loans. On February 29th the People’s Bank of China spurred them on, reducing the amount of cash banks must keep in reserve and so freeing another $100 billion for new lending. Signs of stress are multiplying. The value of non-performing loans in China rose from 1.2% of GDP in December 2014 to 1.9% a year later. Many SOEs do not seem to be earning enough to service their debts; instead, they are making up the difference by borrowing yet more. At some point they will have to tighten their belts and start paying down their debts, or banks will have to write them off at a loss—with grim consequences for growth in either case. An IMF working paper published last year identified credit growth as “the single best predictor of financial instability”.

Yet China is not obviously vulnerable to the two most common types of financial crisis. The first is the external sort, like Asia’s in 1997-98. In such cases, foreign lending sparks a boom that eventually fizzles, prompting loans to dry up. Firms, unable to roll over their debts, must cut spending to save money. As consumption and investment slump, net exports rise, helping bring in the money needed to repay foreign creditors. China does not fit this mould, however. More than 95% of its debt is domestic. Capital controls, huge foreign-exchange reserves and a current-account surplus help defend it from capital flight. The other common form of crisis is a domestic balance-sheet recession, like the ones that battered Japan in the early 1990s and America in 2008. In both cases, dud loans swamped the banking system. Central banks then struggled to keep demand growing while firms and households paid down their debts.

China’s banks are certainly at risk from a rash of defaults. Markets now price the big lenders at a discount of about 30% on their book value. Yet whereas America’s Congress agreed to recapitalise banks only in the face of imminent collapse, the Chinese authorities will surely be more generous. The central government’s relatively low level of debt, at just over 40% of GDP, means it has plenty of room to help the banks. Indeed, with the right policies, China could survive a deleveraging without too much pain.

Begins is the key word.

• China Begins to Tackle Its ‘Zombie’ Factory Problem (WSJ)

China’s leaders two decades ago decided that a combination of restructuring, privatization and massive job cuts was needed to revitalize the economy and shake up state industries weighed down by debt, overcapacity and declining profits. An estimated 20 to 35 million people lost jobs in the late 1990s. The same ills are now back, and reform of the country’s swollen industries is expected to feature prominently in China’s next five-year plan as the National People’s Congress, China’s annual legislative session, starts Saturday in Beijing. But this time around, the government is taking a more modest approach to cutting off its “zombie” factories as it confronts slowing economic growth that has unnerved Chinese leaders and global markets and raised fears of social unrest.

Beijing has outlined plans to cut 1.8 million steel and coal workers over the next five years. To ease social pain, it will put 100 billion yuan ($15.3 billion) into a restructuring fund for severance, retraining and relocation. Economists query whether the initiatives are enough. Beijing aims to cut up to 150 million tons of capacity in its steel industry by 2020, for example, but the annual surplus is currently around 400 million tons, according to the China Iron and Steel Association. The outline of China’s restructuring vision can be seen in its traumatized northeastern rust belt. In Jixi, a coal-dust-covered town of boarded-up buildings and sagging chimneys, provincial money is helping the Heilongjiang LongMay Mining trim its bloated payroll.

Between November and January, some 20,000 LongMay workers were transferred to jobs in farming, forestry and sanitation, among others, said Guo Shenming, a security inspector at the company’s Dongshan mine in Jixi. Workers receive 1,800 yuan ($275) a month for three years from the province, after which the new employer picks up the tab, he said. “Coal is a twilight industry,” he said, “so it’s a good chance for workers to get out.” But the coal-industry retrenchment and the 2014 closure of a steel mill has hit Jixi hard, said Mr. Guo, whose family runs a restaurant. “Families used to buy 10 or more pig’s feet for the Lunar New Year holiday, but this year they only got three or four,” he said. LongMay, which had over 250,000 workers in its heyday, now has well below 200,000. But it still lost 2.23 billion yuan in the first half of 2015, according to China Bond Rating, which is affiliated with the central bank. In November, the provincial government stepped in with a 3.8 billion yuan bailout to help the company with its debts.

Guess this is where you say: Make up your minds already! You can’t micro-manage this.

• PBOC Pulls $129 Billion in Biggest Weekly Withdrawal Since 2013 (BBG)

China’s central bank drained the most funds from the financial system in three years, mopping up excess cash after a reserve-requirement ratio cut earlier this week boosted liquidity. The People’s Bank of China pulled a net 840 billion yuan ($129 billion) in the five days through Friday, data compiled by Bloomberg show. While that was the biggest weekly withdrawal since February 2013, money-market rates barely reacted with the RRR reduction releasing an estimated 685 billion yuan into the banking system. The PBOC kept its open-market seven-day interest rate unchanged at 2.25% on Friday. The seven-day repurchase rate, a benchmark gauge of interbank funding availability, fell one basis point Friday and five basis points for the week, according to a weighted average from the National Interbank Funding Center.

The cost of one-year interest-rate swaps, the fixed payment to receive the floating seven-day repo rate, was little changed at 2.3%. “The PBOC didn’t seem to plan to add excessive liquidity,” said Qu Qing at Huachuang Securities. “Keeping the interest rate of the operations unchanged also indicated its intention to maintain prudent monetary policy. The RRR cut is only replacing the huge amount of reverse repos due this week.” The central bank auctioned 50 billion yuan of seven-day reverse repos on Friday, bringing this week’s total sales to 320 billion yuan. That’s less than a record 1.16 trillion yuan of contracts maturing this week that will drain funds from the financial system. The PBOC injected an unprecedented 1.7 trillion yuan via such operations in the five weeks running up to the Lunar New Year holidays.

Where the newly unemployed can go.

• China To Increase Defence Spending By ‘7-8%’ In 2016 (AFP)

China will raise its defence spending by between 7-8% this year, a senior official has said, a smaller increase than the double-digit rises of the past as Beijing seeks a more efficient military. China’s budget will rise to around around 980bn yuan ($150bn) as the Beijing regime increases its military heft and asserts its territorial claims in the South China Sea, raising tensions with its neighbours and with Washington. Defence spending last year was budgeted to rise 10.1% to 886.9bn yuan ($135.39bn), which still only represents about one-quarter that of the United States. The US defence budget for 2016 is $573bn. “China’s military budget will continue to grow this year but the margin will be lower than last year and the previous years,” said Fu Ying, spokeswoman for the national people’s congress (NPC), the Communist-controlled parliament.

“It will be between 7-8%.” The exact increase will be announced on Saturday at the opening of the NPC, Fu told reporters. The slowdown in spending comes as president Xi Jinping seeks to craft a more efficient and effective People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the world’s largest standing military. At a giant military parade in Beijing last year to commemorate the 70th anniversary of Japan’s World War II defeat, Xi announced the PLA would be reduced by 300,000 personnel. But the event also saw more than a dozen “carrier-killer” anti-ship ballistic missiles rolling through the streets of the capital, with state television calling them a “trump card” in potential conflicts and “one of China’s key weapons in asymmetric warfare”.

As we’ve been saying for a very long time. The inevitability far trumps the timing.

• “I See Bubbles Bursting Everywhere” (CNBC)

Deflationary tides are lapping the shores of countries across the world and financial bubbles are set to burst everywhere, Vikram Mansharamani, a lecturer at Yale University, told CNBC on Thursday. “I think it all started with the China investment bubble that has burst and that brought with it commodities and that pushed deflation around the world and those ripples are landing on the shore of countries literally everywhere,” the high-profile author and academic said at the Global Financial Markets Forum in Abu Dhabi. Price levels are already falling in parts of Europe. Inflation declined by an annualized 0.2% in the euro zone in February, according to an estimate from the European Union’s statistical body. Annualized inflation was flat in Japan in January (the latest month for which there is official data), but rose by a narrow 0.3% in the U.K.

On Thusday, Mansharamani said that financial bubbles had been fueled by “cheap money” created by highly accommodative monetary policy across developed economies. “I mean, we’ve got a bubble bursting, I would argue, in Australian housing markets — that is beginning to crack; South Africa – the whole economy; Canada – housing and the economy; Brazil. We can keep going on and on,” the academic told CNBC. Financial markets have suffered a rocky ride this year, with significant variation across the world. The U.S. benchmark S&P 500 equity index is down 2.8% since the start of 2016, while China’s Shanghai Composite index has tumbled more than 19%. On Thursday, though, markets were in “risk-on” mode. The CBOE’s VIX — a widely used indicator of risk aversion – dipped to its lowest level in 2016 and “safe-haven” U.S. Treasury notes traded at three-week lows.

Banks drive up price of oil so borrowers, before going bankrupt, can pay back loans to … banks.

• UBS: “The Move In Oil Is TOTALLY Short Squeeze Led” (ZH)

Today, one Wall Street firm confirms that indeed the recent move in oil has nothing to do with fundamentals, and everything to do with positioning, and as UBS explains, “the performance is TOTALLY short-squeeze led.” Here’s why:

RECENT ACTION/ SENTIMENT : Yesterday oil ended in the green despite a very large reported crude inventory build, a reflection of how biased to the downside sentiment and positioning already is. Today, crude started in the read and has been mixed from there but moving higher. And both days, the stocks have lead with energy the best performing subsector in the S&P. Now, there is no doubt that the performance today is TOTALLY short-squeeze led. Though it also shows how negative sentiment and positioning is. Interestingly, with energy outperforming the market the last few days for the first time in a very long while, I actually got a few long only generalist type calls yesterday. Nothing concrete but generalists who are underweight the space trying to figure out if this is a turning point…

WHAT HAS HELPED FUEL THIS SHORT SQUEEZE?

• Positioning and sentiment very biased to the short side/ underweight. And as we move up, the move is also exxacerbated by short gamma positions that have to cover at higher levels.

• Despite high oil inventories (and still building), most upstream producers (from Exxon on down) have guided to lower than expected production as a result of lower capex.

• Ongoing hopes of a potential agreement between OPEC and non-OPEC members (seems umlikely but now a meeting set for March 20th is reviving some market hopes).

• A couple of supply issues like Kirkuk/Ceyhan pipeline damage taking longer to repair than expected and Farcados force majeure in Nigeria still on going issue.

• Credit players covering equity shorts — evident today that “good credit names” are underperforming and “bad credit names” outperforming.

• We took a day break from equity issuances in the space ystd and this morning… despite energy’s strong performance. Though rest assured we haven’t seen the end of issuances yet (RRC WLL, RSPP, MUR, CRZO GPORare all top of mind)… by the same token all this energy issuances are helping the credit side of things which has also been the culprit of the issue.One may wonder if the squeeze is forced, or simply momentum driven, although we would like to quickly point us that most of the recent equity offerings by O & G companies who have benefited from the rally have noted in the “use of proceeds” that the raised capital would be used to pay down secured debt, i.e., take out the banks. In other words, it is as if the banks are orchestrating a squeeze to allow the shale companies to raise capital which will then allow them to repay their secured debt to the banks, secured debt whose recoveries as we have recently shown are practically non-existent in bankruptcy.

“As it stands, the people of the nations of monetary union are farther away from the idea of political union than at any time in the past.”

• EU Superstate Would Have No Democratic Legitimacy (Tel.)

The eurozone’s fledgling attempts to create a full-blown fiscal union has no democratic legitimacy, one of the single currency’s founding fathers has warned. Professor Otmar Issing – a former chief economist at the ECB and architect of the euro – said EU policymakers would not dare put their plans to transfer budgetary sovereignty to Brussels before electorates as they would fail at the first hurdle. Speaking of the European Commission’s Five Presidents Report – which lays out plans to shore up the foundations of the euro – Mr Issing said it was a step towards creating a fiscal union “without democratic legitimacy”. “Those who have read [the Five Presidents] report know that. Without political union all transfers will lack democratic legitimacy.

And nobody can be as stupid as to think political union is around the corner,” he told a parliamentary committee at the House of Lords. Prof Issing – who has been a fierce critic of attempts to pool budgetary powers in the euro – said EU elites were afraid to “confront” voters, delaying their plans for integration until after 2017, the year France and Germany hold national elections. “The thrust of all these ideas is going through a back door towards fiscal union,” he said. “Voters in the end will understand what is going on. They will know they are being exploited.” His comments come after prominent voices such as former Bank of England governor Lord King predicted the euro would collapse under the weight of popular disillusion in its weakest economies. But Prof Issing said there was too much “political investment” in the project to allow the euro to collapse.

“It will stay – I am sure about that,” he said. Instead of calling for a giant leap in integration, which would create a euro “superstate” with an EMU parliament and treasury, the German central banker urged policymakers to “stabilise” the current system and return to the original principles of monetary union, which forbids transfers from stronger to weak nations. “In the end, governments are responsible for their own actions,” said Professor Issing. “As it stands, the people of the nations of monetary union are farther away from the idea of political union than at any time in the past.” He also criticised EU plans to set up a banking union that guarantees the deposits of citizens across the 19-country bloc, describing it as an “expropriation of taxpayer money in some countries”.

“The idea of a common deposit insurance is fine, but before you start, you have to clarify bank balance sheets and have a new start. But this is also tricky and complex – there is no simple way out.” Highlighting the democratic constraints the euro has faced since the financial crisis, Professor Issing said he was concerned by developments in Spain and Portugal – where two incumbent bail-out governments have failed to be re-elected after imposing punishing austerity measures. “People have decided for a policy that is different to what is needed for monetary union. This strikes at the core of democracy.”

Going more wrong by the day.

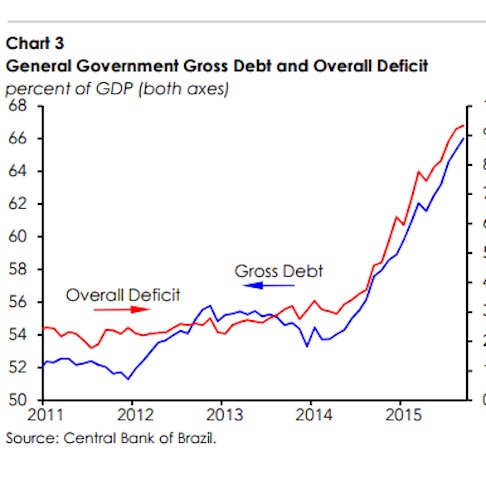

• Brazil’s Economy Slumps To 25-Year Low as GDP Falls 3.8% (Guardian)

Brazil’s economy suffered its worst slump for quarter of a century last year as a global commodity rout, a domestic political crisis and rising inflation forced businesses to slash spending and jobs. Economists warned that the country’s recession had further to run and could deepen amid fresh signs that a drop in demand has continued into 2016. Official figures showed Brazil’s GDP fell 3.8% in 2015, the steepest decline since 1990, when the country was battling hyperinflation. Last year finished on a gloomy note with fourth quarter GDP down 1.4% on the previous quarter against the backdrop of a deepening political corruption scandal. The Brazilian economy is expected to shrink again by more than 3.0% this year, the worst consecutive annual plunges since records began in 1901. Four years ago, the economy was growing by more than 4.0% a year.

The gloomy news will raise pressure on President Dilma Rousseff, who is fighting efforts to impeach her over charges that she used money from state-run banks to plug holes in the budget. More timely figures showed the private sector contracted at a record pace last month. The Brazil composite output index, published by data company Markit, dropped to its lowest since the survey began in 2007. The index, which tracks companies across the economy, dropped to 39 in February, marking the 12th month running below the 50-point mark that separates expansion from contraction. Brazil’s economy had been hit hard by a collapse in commodity and oil prices in the past two years, said Mihir Kapadia at Sun Global Investments. “The situation has been made worse by the high debt levels, especially in foreign currency – essentially in US dollars. Problems of governance, corruption and political issues have created a perfect storm for continued political instability,” Kapadia added.

No, not even the IMF can.

• Only The IMF Can Now Save Brazil (AEP)

Brazil is heading straight into the arms of the IMF. The sooner this grim reality is recognized by the country’s leaders, the safer it will be for the world. The interwoven political and economic crisis has gone beyond the point of no return. The government is frozen. The finance ministry has lost the trust of Brazilian investors and global markets in equal measure. Almost nothing credible is being done to stop the debt trajectory spinning into orbit. Few believe that the ruling Workers Party is either capable or willing to take the drastic austerity measures needed to break out of the policy trap, or that it would suffice at this late stage even if they tried. “There is an enormous fiscal crisis and we’re flirting with a return to hyperinflation. All the debt variables are going in the wrong direction,” said Raul Velloso, the former state secretary of planning.

“There is a loss of confidence in the ability of the government to manage its debts. We face the risk of default,” he said. Three quarters of the budget is effectively untouchable, locked in by a web of welfare payments and regional transfers. President Dilma Rousseff is battling impeachment. Whether she wins or loses over coming months, the congress is too fractured and enflamed to do much about a budget deficit running at over 10pc of GDP. “I have the feeling that nobody wants to take any bold steps, or make any sacrifices,” said Arminio Fraga, the former central bank governor. “Brazil ended up in this situation by doubling down on credit and fiscal expansion. It woke up with the nightmare of a paralyzed country and a ruined model that is not being corrected. It is an economic tragedy,” he told O Estado de Sao Paulo.

Mr Fraga said the collapse is desperately sad because Brazil seemed to be on the right path under president Luis Inacio da Silva, or Lula as everybody knows him. “There was a feeling that the country was getting ahead, and then it vanished. The country suddenly lost itself completely,” he said. It emerged this week that even Lula is under criminal investigation, the latest casualty of the Lava Jato (carwash) scandal. This began as a probe into the abuse of inflated contracts from the state oil giant Petrobras to fund the Workers Party, but is fast engulfing the country’s political elites in a broader purge – akin to Italy’s “mani pulite” scandals in the 1990s. In a sense it is an impressive show of judicial independence. But nobody knows how this will end, and the mood is turning tetchy.

The justice minister resigned this week, angry over pressure from his own Workers Party to rein in the probe. Rui Falcão, the party chief, retorted that basic rights are now being violated by prosecutors acting beyond the rule of law. “We’re seeing the abolition of habeas corpus. It is the democracy of the country that is at stake,” he said. Dilma lost her last chance to win back market trust when her Chicago-trained trouble-shooter, Joaquim Levy, threw in the towel after a year as finance minister, defeated by foot-dragging in the cabinet. Disbelief is by now so pervasive that her government would struggle to restore confidence even if it grasped the nettle. The IMF is the only way out of the impasse.

Only as long as investors can profit, and banks. Not endless.

• Era Of Zero, Negative Interest Rates Could Last For Years: Barclays (Reuters)

The era of zero or negative interest rates, notably in Japan and the euro zone, could extend for several more years as central banks battle persistently low growth and inflation, strategists at Barclays said on Thursday. The downward pressure on interest rates will be strongest in Japan and the euro zone, while the greater flexibility and resilience of the U.S. and UK economies should allow interest rates there to rise quicker, albeit extremely gradually. “Negative nominal interest rates are more than just a passing monetary fad,” Barclays said in its 61st annual Equity Gilt Study. Barclays said the natural rate of interest across the developed world, where borrowing costs are neither stimulative nor restrictive given an economy’s potential growth and inflation rates, is lower than where nominal rates currently stand.

The study finds that real equilibrium policy rates are near-zero across the developed world and may need to fall further below zero in the euro zone and Japan for interest rate policy there to become “sufficiently accommodative”. Michael Gapen, the bank’s chief U.S. economist and co-author of the report, said the way to avoid a repeat of Japan’s experience over the last two decades is to restructure “zombie” banks and firms so that the broader private sector can clean itself up and get itself in shape to start growing again. This could be most difficult in the euro zone, where the mix of slow growth, low inflation and a fractured banking system blighted by bad loans will make it difficult for the ECB to escape low or negative rates.

“The era of low or even negative interest rates across the developed world, particularly in Japan and the euro zone, could last for several years to come,” Gapen said. In 1995 the Bank of Japan lowered its main interest rate to 0.5% to try and reflate the flagging economy. Rates have never been higher since and the BOJ has also injected trillions of yen worth of stimulus via quantitative easing bond purchases. The BOJ is still fighting that battle against low growth and deflation. Earlier this year it adopted negative interest rates on certain bank deposits and became the first G7 rich country to have yields on its benchmark 10-year bonds fall below zero. “We don’t see a ‘Japanification’ of the world. But accommodative policy is here to stay,” said Christian Keller, head of economics research at Barclays and also a co-author of the study. “Before we get to the limits (of these policies), central banks will persist with zero and negative rates,” he said.

“This is bad history and worse economics.”

• Osborne’s Desire To Further Cut Spending Makes Little Sense (Wolf)

George Osborne wants to burnish his image as an iron chancellor of the exchequer. He has already committed to achieving a fiscal surplus by 2019-20. He now suggests that further tightening of fiscal policy may be needed in response to the “storm clouds” he identified when in Shanghai last week. Mr Osborne may be preparing for bad news in his Budget on March 16. The question is whether his plan makes sense. The answer is no. The fiscal objective is itself questionable. The aim is to achieve an overall surplus, unless growth drops below 1%. This is to offer respite in the event of a recession. Just compare what the government would do if a deficit opened up while the economy grew 1.1% for three years (namely, tighten policy), with what it would do if it grew 3%, 0.9% and then 2% (not tighten at all in the second year).

Why should an overall fiscal surplus be important, anyway? The answer is that it is a quicker way to lower the ratio of debt to GDP. But that would only be true if achieving the surplus did not itself slow the growth of GDP. As the Institute for Fiscal Studies notes in its Green Budget, “running a surplus is not necessary to bring debt down as a share of national income”. Moreover, if the government is in a position to invest by borrowing at low real interest rates, as now, it makes sense to do so. The government must worry about its balance sheet, not just its debt. Yet the absurdity of the target is brought out better still by the comments Mr Osborne made last week. He said, first, “this country can only afford what it can afford”; second, “the economy is smaller than we thought”; third, the UK must tighten further, to ensure “economic security”; and, finally, “the last time we didn’t [live within our means] we were right in the front rank of nations facing economic crisis”.

This is bad history and worse economics. It is a myth that the UK’s crisis was due to a failure of the government to live within its means. The truth is the opposite. The government did not have a fiscal crisis. The country had a financial crisis whose economic results were cushioned by the government’s deficits. Again, it is not true that running a fiscal surplus year after year is either necessary or sufficient to achieve “economic security”. It is more important to create a robust financial sector. Yet pressure from the Treasury today seems to be to relax constraints. That may well be far riskier for the UK economy in the long run than modest fiscal deficits.

Ari Andicropoulos.

• The Economy Simply Explained (AA)

Sometimes my friends tell me that they try to read them, but my posts are too complicated. I am using jargon that they don’t understand and probably they are too long and confusingly written. To remedy this, I have decided to try to write a simplified version of this piece I wrote about how the economy works.

How can one picture the economy? The economy should be viewed as a flow of money. This may seem straightforward, but mainstream economic models do not include money at all. And yet, a lot of the workings of the economy can be understood by looking at who receives money and how much of it they spend.

If everyone is working and producing goods and services, then people need to buy these goods and services. In order for people to buy these products they need to have enough money.

Money received by people for producing things is then spent by these people on more things. This cycle repeats itself and makes the economy run.

What if people don’t have enough money? They can’t buy the goods and services. In a perfect world, the price of everything would go down so that all of what is produced can be bought. Unfortunately, in reality this is not the case.

Why can’t prices go down very easily? The reason that prices can’t adjust very easily to not enough money is that people’s wages tend not to go down. This is called ‘stickiness of wages’. Because people generally don’t like having pay cuts, producers can’t reduce prices or they will be making goods at a loss.

If they can’t reduce prices, what do they do? Instead they cut production and make people unemployed. This then, in turn, reduces the amount of money that people have to buy things. Leading to further job losses.

Eventually what would happen? Without any government intervention, in the end prices and wages would fall enough so that everyone could have a job again. But it is a long and painful process. It is much better to ensure that the correct amount of money is running therough the system.

How much money is the correct amount? A generally accepted nominal GDP growth target is 5% per year. This means that in total 5% more value in goods and services are produced each year. Some of this increase is due to inflation – one pays more for the same number of goods. And some of this is growth – more goods are produced.

But if 5% more £ worth of goods and services are produced, doesn’t that mean that people need to spend 5% more money each year than the year before? Exactly. Every year, for the economy to be healthy, 5% more money needs to be spent than the year before.

Where does this extra money come from? This is a very good question. And it is one that seems to be ignored by most economists.

The problem we have with the economy today is that actually it is being drained of money. If £1m of goods are produced and sold, then in the next year only approximately £970,000 will be spent. People are saving the other £30,000.

To be more exact, the gap between the amount people are saving and the amount of people’s savings from previous years that they are spending comes to 3%, maybe even 4%, of GDP.

Why is this gap so large? There are a number of reasons but it mainly has to do with the difference in spending of the people who receive the money. Working people on low and medium incomes tend to spend most of the money they receive. But savers receiving interest and dividends spend less of it in the economy.

You expected something else? That German beer purity law (Reinheitsgebot) is 500 years old.

• Monsanto’s RoundUp Found in 14 Popular German Beers (NS)

Want a round of Round Up with your beer? The German beer industry is in shock after finding that 14 different popular beer brands have traces of the ‘probably’ carcinogenic herbicide, glyphosate – an ingredient found in Monsanto’s best-selling weed killer, Round Up. Germany’s Agricultural minster is playing down the risks in order to save one of the countries’ best-selling exports. Glyphosate levels were as high as 30 micrograms per liter, even in beer that is supposed to be brewed from only water, malt, and hops. This finding by the Munich Environmental Institute calls into question the rampant spraying of Round Up on both GMO and non-GMO crops around the world, and casts doubt upon Germany’s 500-year-old beer purity law.

The EU Commission was looking to extend approval for the use of glyphosate in Germany, and other EU countries in April for another 15 years. The current license runs out this summer. Following the findings by France, that glyphosate is likely a human carcinogen, as well as the World Health Organization’s cancer research arm, the IARC, finding that glyphosate is a probable carcinogen, glyphosate in Germany’s coveted beer is not a positive discovery for the makers of this herbicide, which include companies like Monsanto. Germany’s farm federation has denied responsibility, saying that malt derived from glyphosate-sprayed barley has been banned. The group admits, though, that glyphosate could have been used on farms prior to the ban, meaning barley could still be grown in glyphosate-drenched soil.

The Bremen office of the brewery giant Anheuser-Busch described the institute’s findings as “not plausible,” citing a bill of health issued by Germany’s Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) that the amounts of glyphosate found in beer did not pose a threat to consumers. In a statement, the Institute said: “An adult would have to drink around 1,000 liters (264 US gallons) of beer a day to ingest enough quantities to be harmful to health.” As with other Big Ag deniers, they seem to forget that glyphosate exposure comes from multiple sources, aside from just contaminated beer.

This will make Erdogan all the more dangerous.

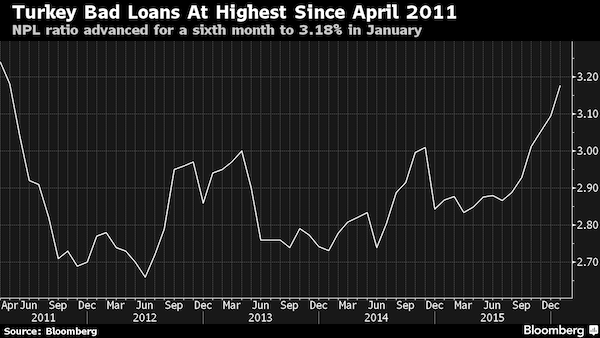

• Ballooning Bad Loans in Turkey Worsen as Tourists Flee (BBG)

The ailments afflicting Turkey’s economy that have triggered a surge in bad loans look poised to get worse before they get better. Non-performing loans at the nation’s lenders climbed to 3.18 percent of total credit in January, the sixth straight monthly increase and the highest proportion in almost five years, according to data this week from the Ankara-based Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency. BofA Merrill Lynch and Commerzbank said in Februrary corporate distress is deepening in Turkey, making it harder for companies to pay down debts. The rise in bad loans is compounding the challenges for Turkey’s $814 billion banking industry as a combination of currency depreciation, Russian sanctions and waning tourist visits amid a spate of terrorist attacks weigh on the economy.

As the central bank limits funding to tame inflation, the highest borrowing costs in four years and a slow down in loan growth are piling pressure on indebted businesses. “The trend is likely to increase and intensify,” said Apostolos Bantis, a Commerzbank credit analyst in Dubai, who said loans and lira-denominated bonds would be exposed. “While I don’t see the situation running out of control, the impact of Russian sanctions, the blow to the tourism industry, higher funding costs and the weaker currency will all take a toll on the corporate sector,” he said before the data.

Would tend to agree. But don’t underestimate the coming financial crash.

• The Syrian War Will Define The Decade (Reuters)

Many decades have a war that defines them, a conflict that points to much broader truths about the era — and perhaps presages larger things to come. For the 1930s, the Spanish Civil War, the three-year fight between Fascists (helped by Nazi German) and Republicans (armed by the Soviet Union) pointed to the far larger global disaster to come. For the 1980s, the Soviet battle to control Afghanistan, a bloody mess of occupation and insurgency, helped bring forward the collapse of the Soviet Union and set the stage for 9/11 and modern Islamist militancy. For the 1990s, you can take your pick of the Balkans, Somalia, Rwanda or Democratic Republic of Congo. For the 2000s, it was Iraq — the ultimate demonstration of the “unipolar moment” and the limits, dangers and sheer short-livedness of America’s status as unchallenged global superpower.

We are, of course, little more than half way through the current decade. Already, however, it looks as though it has to be Syria’s civil war. In pure human terms, the war dwarfs any other recent conflict. Estimates of the number of Syrian dead range from 270,000 to 470,000 people. The UN estimates up to 7.6 million Syrians are displaced within their own country, with up to 4 million fleeing their homeland. From its relatively small beginnings as a largely unarmed revolt, the Syrian conflict has now dragged in more than a half-dozen countries. Its broader implications continue to grow by the month. While not the sole cause of Europe’s migrant crisis, Syrians make up a significant proportion — perhaps even the majority — of new arrivals on the continent. The sheer numbers are producing political strains that have already torn up the ideal of a “borderless” Europe and may yet wreck the entire EU project.

Syria has exemplified what Financial Times columnist Gideon Rachmann calls a “zero-sum world.” From the beginning, rival regional powers — particularly Shi’ite Iran and Sunni states led by Saudi Arabia — approached the conflict with the assumption that neither side could afford to back down or compromise without letting the other win. From that perspective, Syria is part of a larger regional confrontation that encompasses the war in Yemen, the long-term sectarian battle for control of Iraq and, of course, attempts to rein in Iran, in general, and its nuclear program, in particular. Increasingly, though, the war in Syria has become part of the wider, potentially more dangerous confrontation between Western powers and Russia. That confrontation also goes back years — through Kosovo and the Balkans to the Cold War.

It’s already lost.

• EU Fate At Stake On Muddy Greek Border (Reuters)

In muddy fields straddling the border with Macedonia, a transit camp hosting up to 12,000 homeless migrants in filthy conditions is the most dramatic sign of a new crisis tearing at Greece’s frayed ties with Europe and threatening its stability. For the last year, Greece has largely waved through nearly a million migrants who crossed the Aegean Sea from Turkey on their way to wealthier northern Europe. Now, on top of a searing economic crisis that took it close to ejection from the euro zone a year ago, the European Union’s most enfeebled state is suddenly being turned into what Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras calls a “warehouse of souls”. At least 30,000 people fleeing conflict or poverty in the Middle East and beyond are bottled up in Greece after Western Balkan states effectively closed their borders.

Up to 3,000 more are crossing the Aegean every day despite rough winter seas. “This is an explosive mix which could blow up at any time. You cannot, however, know when,” said Costas Panagopoulos, head of ALCO opinion pollsters. Men, women and children from Afghanistan, Syria and Iraq are packed like sardines in a disused former airport terminal in Athens, crammed into an indoor stadium or sleeping rough in a central square, where two tried to hang themselves last week. The influx is severely straining the resources of a country barely able to look after its own people after a six-year recession – the worst since World War Two – that has shrunk the economy by a quarter and driven unemployment above 25%.

After years of austerity imposed by international lenders, who are now demanding deeper cuts in old-age pensions, ordinary Greeks say they feel abandoned by the European Union. A staggering 92% of respondents in a Public Issue poll published by To Vima newspaper last Sunday said they felt the EU had left Greece to fend for itself. The poll was taken before the European Commission announced €300 million in emergency aid this year to support relief organizations providing food, shelter and care for the migrants. But such promises do little to soften public anger. “I want to spit at them,” said 40-year-old Maria Constantinidou, who is unemployed. “Those European leaders .. should each take 10 migrants home, feed them, look after them and then see how difficult things are.”

Greeks are Menschen.

• Pensioners Share Their Bread With Refugees At Greek Border (Reuters)

Each day, Demetrios Zois buys two loaves of bread. One is for his family, and one for whoever comes knocking on his door. In the past year, there have been plenty of unexpected visitors. He is among 100 mainly elderly people living in Greece’s border community of Idomeni, which has become the focal point of a growing migrant crisis that is proving too big for the country to handle. Around 30,000 migrants and refugees were stranded in Greece on Thursday, with just over a third of them at Idomeni, waiting for the border with Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) to open. “We feel very bad for them. We understand they are hungry, but they are 10,000 and we are 100. If more come what will happen?” Zois, an 82-year-old pensioner, told Reuters.

He and his friend Theodoros Moutaftsis watch with growing concern as a tent city in the meadows outside their homes get bigger by the day. “It’s the first thing we check when we wake up in the morning, whether they have gotten closer to the village,” said Moutaftsis, 79. “That and if anything is missing,” he adds. Ten hens disappeared from his garden last month, and he thinks it was people from the camp. “These poor people are hungry. The state isn’t here to help them. It’s totally absent,” he said. There were anything between 11,000 and 12,000 people at the transit camp on Thursday, waiting for the border gate to open to continue their trek further in to Europe.

This is flat-out illegal. In general, push back is not permitted. International law says that at the very minimum they would have to weigh every single case on an individual basis.

• EU Mulls ‘Large-Scale’ Migrant Deportation Scheme (AP)

Turkey is under growing pressure to consider a major escalation in migrant deportations from Greece, a top EU official said Thursday, amid preparations for a highly anticipated summit of EU and Turkish leaders next week. European Council President Donald Tusk ended a six-nation tour of migration crisis countries in Turkey, where 850,000 migrants and refugees left last year for Greek islands. “We agree that the refugee flows still remain far too high,” Tusk said after meeting Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu. “To many in Europe, the most promising method seems to be a fast and large-scale mechanism to ship back irregular migrants arriving in Greece. It would effectively break the business model of the smugglers.”

Tusk was careful to single out illegal economic migrants for possible deportation, not asylum-seekers. And he wasn’t clear who would actually carry out the expulsions: Greece itself, EU border agency Frontex or even other organizations like NATO. Greek officials said Thursday that nearly 32,000 migrants were stranded in the country following a decision by Austria and four ex-Yugolsav countries to drastically reduce the number of transiting migrants. “We consider the (FYROM) border to be closed … Letting 80 through a day is not significant,” Migration Minister Ioannis Mouzals said. He said the army had built 10,000 additional places at temporary shelters since the border closures, with work underway on a further 15,000. But a top U.N. official on migration warned that number of people stranded in Greece could quickly double.