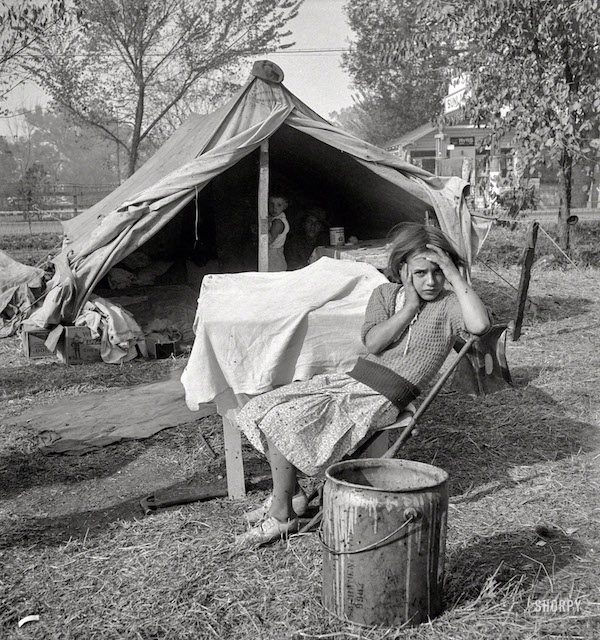

Dorothea Lange Children and home of cotton workers at migratory camp in southern San Joaquin Valley, CA 1936

My long time pal Jesse Colombo, now at Real Investment Advice, recently linked on Twitter to a Zero Hedge article, which quoted CoreLogic as saying more than half of American homes are overvalued. CoreLogic calls itself “a leading provider of consumer, financial and property data, analytics and services to business and government.”

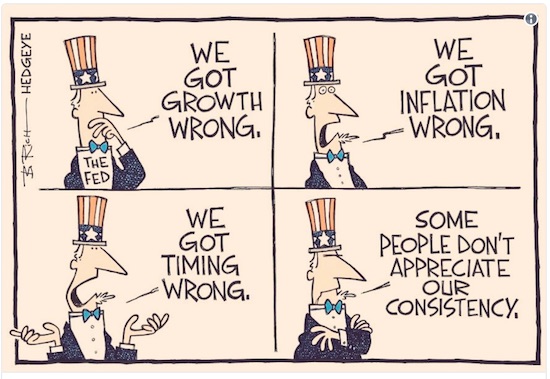

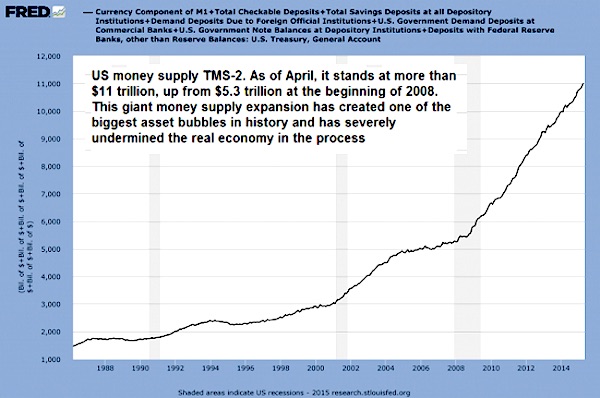

Well, CoreLogic is way off. All American homes are overvalued. How can we tell? It’s easy. It’s so easy it’s perhaps no wonder that people overlook the reasons why. But we all know them: The Fed has pushed some $20 trillion down the throats of the financial system. It has also lowered interest rates to near zero Kelvin. Then the government added a “relaxation” of lending standards and an upward tweak of credit scores. And Bob’s your uncle.

These measures haven’t influenced just half of US homes, they’ve hit every single one of them. Some more than others, not every bubble is as big as San Francisco’s, but the suggestion that nearly half of homes are not overvalued is simply misleading. It falsely suggests that if you buy a home in the ‘right’ place, you’ll be fine. You won’t be. The Washington-induced bubble will and must pop, and precious few homes will be ‘worth’ what they are ‘worth’ today.

Here’s what Jesse tweeted along with his link to the Zero Hedge article:

“Almost half of the US housing market is overvalued” – this is why U.S. household wealth is also overvalued/in an unsustainable bubble.

He followed up with:

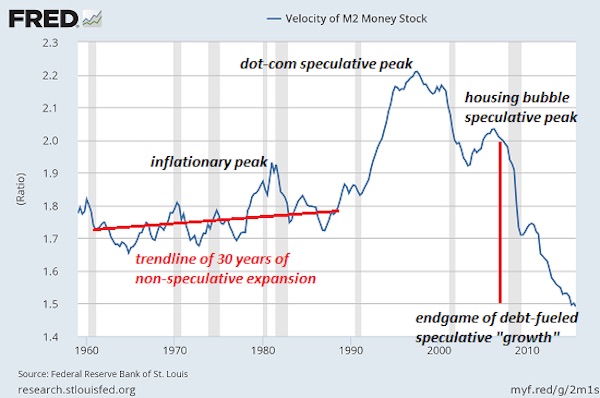

U.S. household wealth is in a bubble thanks to Fed-inflated asset prices. This is creating a “wealth effect” that is helping to drive our spurious economic recovery. This economy is nothing but a sham. It’s smoke and mirrors. Wake the F up, everyone!!!

My reaction to this:

Sorry, my friend Jesse, but every single US home is overvalued. It just depends on the vantage point you look from. All prices have been distorted by the Fed’s policies, not just half of them. Arguably some more than others, but can that be the core argument here?

Jesse’s reply:

Yes, that’s a good point.

Another long time pal, Dave Collum, chimed in with a good observation:

I think even us bunker monkeys start recalibrating, no matter how hard we try to maintain what we believe to be perspective.

Yes, we’ve been at this for a while. Even if Jesse was still a student when he started out. We’ve been doing it so long that he recently wrote an article named: Why It’s Right To Warn About A Bubble For 10 Years. And he’s right on that too.

Let’s get to the article the conversation started with:

More Than Half Of American Homes Are Overvalued, CoreLogic Warns

CoreLogic reports that residential real estate prices nationwide increased 6.9% year over year from April 2017 to April 2018. The firm’s Home Price Index (HPI) also shows a 1.2% rise on the month-over-month basis from March to April 2018. This has certainly sparked the debate of housing affordability across the nation with many millennials struggling to achieve the American dream.

CoreLogic Market Condition Indicators showed that 40% of the 100 largest metropolitan areas were overvalued in April, compared to 28% undervalued, and 32% in line with valuations. The report uncovers a shocking discovery that of the nation’s top 50 largest residential real estate markets, 52% were overvalued in April.

CoreLogic’s methodology behind overvalued housing markets “as one in which home prices are at least 10% higher than the long-term, sustainable level, while an undervalued housing market is one in which home prices are at least 10% below the sustainable level.”

The CoreLogic people probably mean well, but they also probably don’t want to rattle the cage. It’s not really important. As soon as someone starts talking about a ‘sustainable level’ for home prices, you can tune out. Because no such thing exists. Unless you first take those $20 trillion out of the ‘market’, free up interest rates, tighten lending standards and lower credit scores. Only then MAY you find a ‘sustainable level’ for prices.

Historically a house in the US cost around 3 to 4 times the median annual income. During the housing bubble of 2007 the ratio surpassed 5 – in other words, the median price for a single-family home in the United States cost more than 5 times the US median annual household income. According to Mike Maloney, this ratio is heavily influenced by interest rates. When interest rates go down the affordability of a house goes up, so people spend more money on a house. Interest rates have now been falling since 1981 when they peaked at 15.32% (for a 10-year US treasury bond).

Mike Maloney, another longtime friend of the Automatic Earth, is dead on. Price to income is a useless point unless you include interest rates in the calculation. And then you can get large differences. Since interest rates have been falling for 37 years, count on them to rise. And see what that does to your model.

“The best antidote for rising home prices is additional supply,” said Dr. Frank Nothaft, chief economist for CoreLogic. “New construction has failed to keep up with and meet new housing growth or replace existing inventory. More construction of for-sale and rental housing will alleviate housing cost pressures,” Nothaft added.

Right, yeah. Now we know the CoreLogic mindset. The more you build, the better home prices will be. Just one of many problems with that is that if you really expect prices to fall once you build, people will build fewer houses, because profit margins fall too. The whole idea that we can save housing markets by simply building ever more has never rung very true. But that’s for another day.

In a recent op-ed piece via The Wall Street Journal, Paul Kupiec and Edward Pinto place the blame on the government for creating another real estate bubble through “loose mortgage terms pushing home prices up.” They claim that mortgage underwriters need to tighten standards.

“Home prices are booming. So far, 2018 has posted the strongest growth since 2005. “About 60% of all U.S. metros saw an acceleration in the rate of price increases through February this year,” according to Housing Wire. Since mid-2012, real home prices have increased 28%, according to data from the American Enterprise Institute. Entry-level home prices are up about double that rate. In contrast, over the same period household income has barely kept pace with inflation. The current pace of home-price inflation is increasing the risk of another housing bubble.

The Fed is raising rates -finally- and home prices grow at the fastest rate in 13 years. Over the past 6 years prices are up 28%. Entry level homes are up more than 50% in that time frame. That is just profoundly scary. It’s like Dante’s descent into hell. And no, it’s not true that “The current pace of home-price inflation is increasing the risk of another housing bubble”. We’re already caught up head first in a new housing bubble.

“The root of the problem is declining underwriting standards. In April Freddie Mac announced an expansion of its 3% down-payment mortgage, the better to compete with the Federal Housing Administration and Fannie Mae . Such moves propel home prices upward. Because government agencies guarantee about 80% of all home-purchase mortgages, their underwriting standards guide the market.

Making lending even more dangerous, CNBC recently reported that “credit scores may go up” because new regulatory guidance allows delinquent taxes to be excluded when calculating credit scores. These are only some of the measures that “expand the credit box” and qualify ever-shakier borrowers for mortgages.”

As I said before: if you lower lending -and underwriting- standards and artificially raise credit scores, then yes, you can keep the bubble going for a while longer. But it overvalues properties. You’re just moving goalposts.

“During the last crisis, easy credit led home prices to rise at an unsustainable pace, leading marginally qualified borrowers to stretch themselves thin. Millions of Americans’ dreams became nightmares when the housing market turned. The lax underwriting terms that helped borrowers qualify for a mortgage haunted many households for the next decade.”

No, it’s not just homes. Stocks and bonds as just as overvalued. Because of a behemoth attempt at making the economy look good, even though it’s entirely fake. No price discovery, no market, just central banks and tweaking standards and surveys. C’mon, we all know where this must go. We just don’t want to know. So this Marketwatch piece gets a wry smile at best:

America Is House-Rich But Cash-Poor

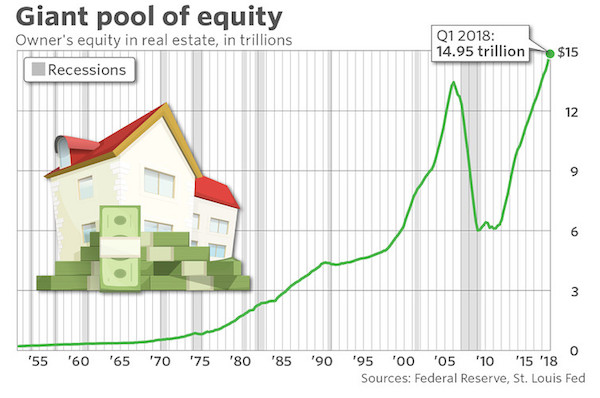

The housing market has not only recovered from the Great Recession, it’s heated up. According to an analysis from Attom Data, nearly 14 million Americans are now “equity rich” – meaning they have at least 50% equity in their homes. It bears repeating that many owners and communities are not so lucky: over a million Americans are underwater, and some cities and towns are still reeling under the weight of abandoned and vacant homes and stagnant micro-economies. But for most of the country, rapidly rising home prices and a dearth of anything else to buy means people are staying in their homes longer, allowing them to accrue more and more equity: $15 trillion worth, to be exact.