Anthony Van Dyck Self portrait with sunflower 1632

More from Andrew Korybko on a interesting theme: how the sanctions on Russia created a whole new energy supply line.

Andrew Korybko:

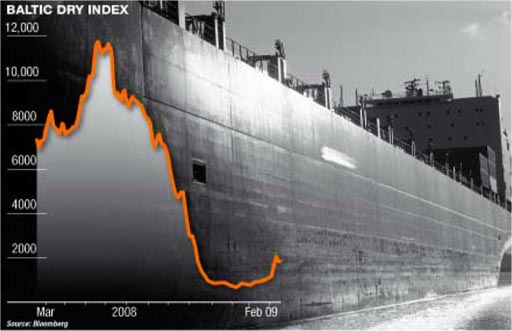

Indian media revealed in mid-January that their country had been processing and re-exporting discounted Russian oil to the West, including the US, in a move that discredited the spirit of that de facto New Cold War bloc’s anti-Russian sanctions. Most observers brushed off those reports since they went against their worldview wherein it was taken for granted that the US-led West’s Golden Billion wouldn’t ever relieve pressure on Russia by having India serve as the middleman in their oil trade.

According to an expert quoted by Bloomberg in their latest report titled “Oil’s New Map: How India Turns Russia Crude Into The West’s Fuel”, “India’s willingness to buy more Russian crude at a steeper discount is a feature, not a bug, in the plan of Western nations to impose economic pain on Putin without imposing it on themselves.” Another one was cited as saying that “US treasury officials have two main goals: keep the market well supplied, and deprive Russia of oil revenue.”

That other expert added that “They are aware that Indian and Chinese refiners can earn bigger margins by buying discounted Russian crude and exporting products at market prices. They’re fine with that.” This insight from Bloomberg, which is held in high regard as one of the world’s premier business outlets, completely shifts the paradigm through which observers interpret the energy dimension of the Golden Billion’s anti-Russian sanctions.

The “official narrative” up until this point was that they were aimed bankrupting the Kremlin in the hopes that it would immediately stop its ongoing special operation and perhaps even “Balkanize” if the desired economic collapse catalyzed uncontrollable socio-political processes like during the late 1980s. The New York Times recently admitted that the anti-Russian sanctions failed, however, pointing to reputable evidence that this targeted state’s economy has stopped contracting and even began to grow.

In the face of these “politically inconvenient” facts, it was thus foreseeable in hindsight that the “official narrative” would have to more comprehensively change in an attempt for the Golden Billion to “save face” before its people, ergo Bloomberg’s latest contribution to this perception management end. The public is now being gaslighted into thinking that the sanctions were never meant to bankrupt the Kremlin, stop its special operation, or “Balkanize” Russia, but just erode a little bit of its revenue.

The reality is that the outcome reported upon by Bloomberg is indeed a “bug” and not a “feature” like they’re claiming in hindsight out of desperation to revise history for self-interested soft power reasons. The Golden Billion didn’t fully forecast the lasting consequences of their sanctions since they naively took for granted that they’d immediately bankrupt the Kremlin, stop its special operation, and subsequently “Balkanize” Russia, none of which ultimately transpired.

They can’t rescind their unilateral economic restrictions though since that would be an unprecedented soft power victory for Russia, hence why they began putting feelers out across the market to explore alternative workarounds for ensuring the reliability of their imports, albeit at a premium. India’s pragmatic policy of principled neutrality towards the Ukrainian Conflict in full defiance of US demands upon it to “isolate” Russia ended up being an inadvertent godsend for the West in this context.

Had that globally significant Great Power not ramped up its purchase of Russian oil to the extent that it did in order to withstand the systemic shocks caused by the West’s sanctions and which destabilized dozens of fellow Global South states, then there wouldn’t be excess supply for re-export. After helping them meet their needs, which wasn’t part of some “5D chess master plan” between India and the West but the organic outcome of how events unfolded, they reduced their pressure upon it as a quid pro quo.

It was difficult to explain late last year why the US noticeably began reducing pressure on India to distance itself from Russia, but it was thought at the time that this was simply a delayed recognition of geostrategic reality and was being done for pragmatism’s sake to retain their strategic ties. Now, however, it appears as though India’s indispensable role in the global energy market as the middleman in facilitating the now-taboo Russian-Western energy trade played a role in the US’ policy recalibration.

From this insight, it can be concluded that India succeeded not only in resisting US-led Western pressure upon it vis-à-vis its relations with Russia, but also unwittingly ended up doing the Golden Billion a favor in the process by placing itself in the position to ensure the reliability of their energy imports. This observation speaks to its newfound role as the kingmaker in the New Cold War, which will imbue it with increasingly more influence within the global systemic transition the longer that this struggle continues.

We try to run the Automatic Earth on donations. Since ad revenue has collapsed, you are now not just a reader, but an integral part of the process that builds this site. Thank you for your support.

Support the Automatic Earth in virustime. Click at the top of the sidebars to donate with Paypal and Patreon.