Paul Gauguin Farm in Brittany 1894

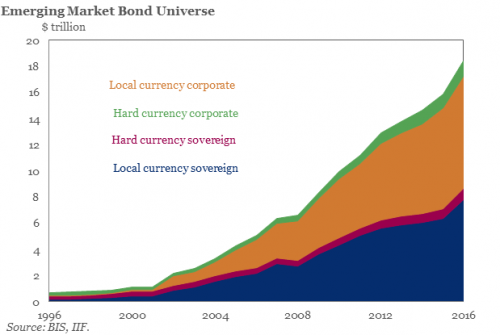

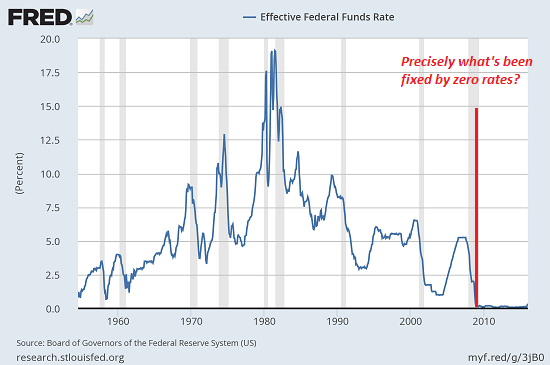

If central banks and governments have really lost control over bonds, find shelter.

• Market Euphoria May Turn to Despair If 10-Year Yield Jumps to 3% (BBG)

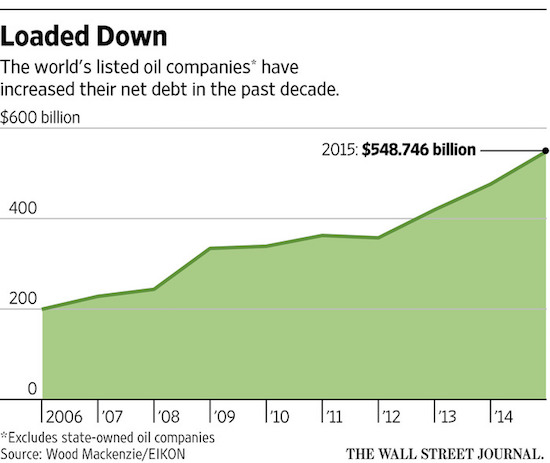

It’s getting harder and harder to quarantine the selloff in Treasuries from equities and corporate bonds. The benchmark 10-year U.S. yield cracked 2.7% on Monday, rising to a point many forecasters weren’t expecting until the final months of 2018. For over a year, range-bound Treasuries helped keep financial markets in a Goldilocks state, with interest rates slowly rising due to favorable forces like stronger global growth and the Federal Reserve spearheading a gradual move away from crisis-era monetary policy. Yet the start of 2018 caught many investors off guard, with the 10-year yield on pace for its steepest monthly increase since November 2016. It’s risen 30 basis points this year and reached as high as 2.73% in Asian trading Tuesday.

Suddenly, they’re confronted with thinking about what yield level could end the good times seen since the presidential election. For many, 3% is the breaking point at which corporate financing costs would get too expensive, the equity market would lose its luster and growth momentum would fade. “We are at a turning point in the psyche of markets,” said Marty Mitchell, a former head government bond trader at Stifel Nicolaus & Co. and now an independent strategist. “A lot of people point to 3% on the 10-year as the critical level for stocks,” he said, noting that higher rates signal traders are realizing that quantitative easing policies really are on the way out.

U.S. stocks have set record after record, buoyed by strong corporate earnings, President Donald Trump’s tax cuts and easy U.S. financial conditions. The S&P 500 Index has returned around 6.8% this year, once reinvested dividends are taken into account, and the U.S. equity benchmark is already higher than the level at which a Wall Street strategists’ survey last month predicted it would end 2018. What often goes unsaid in explaining the equity-market exuberance is that Treasury yields refused to break higher last year. Instead, they remained in the tightest range in a half-century, allowing companies to borrow cheaply and forcing investors to seek out riskier assets to meet return objectives.

It’s all bonds, not even just sovereign bonds. Investors will move from equities into bonds all over the place.

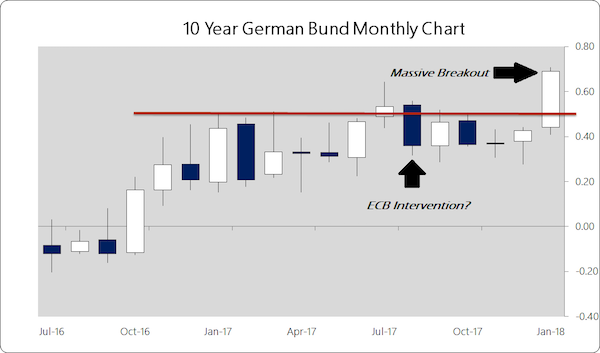

• Forget Stocks, Look At EU Bonds – They Are The Real Problem (Luongo)

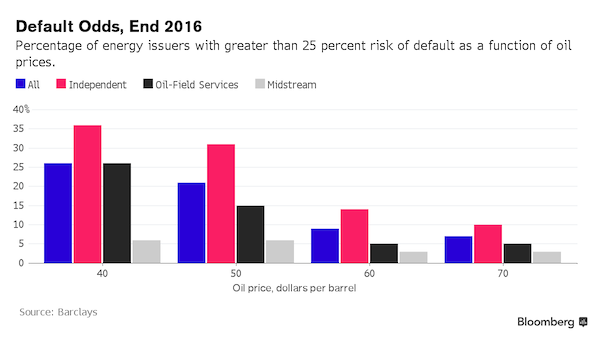

While all the headlines are agog with stories about the Dow Jones dropping a couple hundreds points off an all-time high, German bunds are getting killed right before our eyes. The Dow is simply a market overdue for a meaningful correction in a primary bull market. And it’s a primary bull market brought on by a slow-moving sovereign debt crisis that will engulf Europe. It’s not the end of the story. Hell, the Dow isn’t even a major character in the story. In fact, similar stories are being written in French 10 year debt, Dutch 10 year debt, and Swiss 10 year debt. These are the safe-havens in the European sovereign debt markets. Meanwhile, Italian 10 year debt? Still range-bound. Portuguese 10 year debt? Near all-time high prices. The same this is there with Spain’s debt. All volatility stamped out. Why? Simple. The ECB.

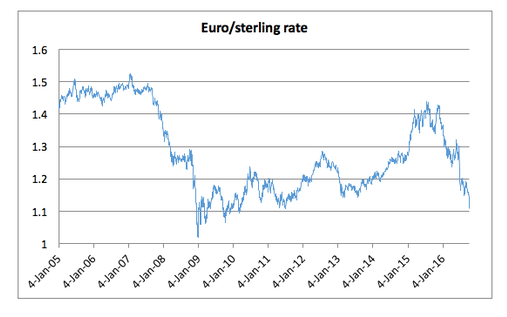

The ECB’s quantitative easing program and negative interest rate policy (NIRP) drove bond yields across the board profoundly negative for more than a year. [..] the ECB is trapped and cannot allow rates to rise in the vulnerable sovereign debt markets — Italy, Portugal, Spain — lest they face bank failures and a real crisis. The problem with that is, the market is scared and so they are selling the stuff the ECB isn’t buying – German, French, Dutch, Swiss debt. In simple terms, we are seeing the flight into the euro intensify here as investors are raising cash. The euro and gold are up. The USDX continues to be weak even though capital is pouring into the U.S. thanks to fundamental changes to tax and regulatory policy under President Trump. In the short term Dow Jones and S&P500 prices are overbought. Fine. Whatever. But, the real problem is not that. The real problem is the growing realization in the market that governments and central banks do not have an answer to the debt problem.

[..] The U.S. economy is about to be unleashed by Trump’s tax cut law. It will be able to absorb higher interest rates for a while. Yield-starved pension funds, as Armstrong rightly points out, will be bailed out slightly forestalling their day of reckoning. And in doing so, higher rates in the U.S. are driving core-rates higher in Europe. An overly-strong euro is crushing any hope of further economic recovery in the periphery, like Italy. The debt load on Italy et.al. has increased relative to their national output by around 20% since the end of 2016. This will put the ECB at risk of a massive loss of confidence when Italian banks start failing, Italy’s budget deficit starts expanding again and hard-line euroskeptics win the election in March. As capital is drained out of Europe into U.S. equities, the dollar, gold and cryptocurrencies, things should begin to spiral upwards rapidly.

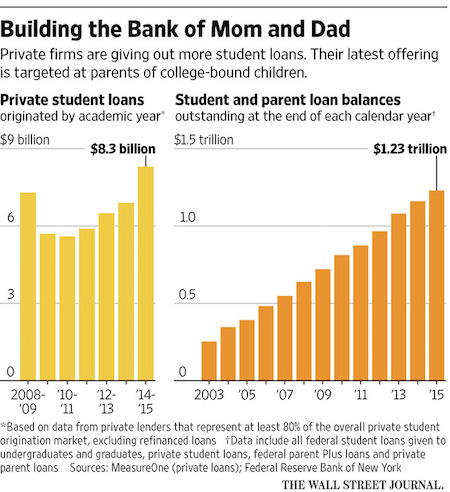

See? More bonds. Meredith Whitney was 10 years early.

• The Ticking Time Bomb in the Municipal-Bond Market (Barron’s)

There’s a looming disaster in the market for municipal debt. Every market participant knows about it, and there isn’t much any of them can do about it. Many state and local governments, even more than corporations, have promised generous pensions they can’t afford. The promises may have looked plausible in the past, especially during the dot-com boom, when money that pension funds put in the markets was doubling. When the market crashed, so did their returns—and, a few years later, the global financial crisis took out another substantial chunk. And with interest rates at historic lows, bonds have failed to deliver the income the funds relied on. While governments delay dealing with the problem as long as they can, analysts and researchers are wondering if we have reached the point of no return. For investors in municipal bonds, it could mean future defaults and losses.

“We are increasingly wary of high pension exposure, especially among state and local credits,” the Barclays muni-research team wrote this month, citing “inflated return targets, low funded ratios, growing obligations, perhaps heavy allocations to equities and compressed tax revenues make for especially adverse conditions.” What’s more, “short-term investment gains won’t be sufficient to plug liability gaps.” Yet many pensions still assume they will be able to generate the returns they saw in the past. New Jersey’s pension and the California Public Employees’ Retirement System have lowered their assumed rate of return to 7%. But with the 30-year Treasury yielding less than 3% and stocks already at record highs, it’s unclear how public markets can generate 7%—which is why many pensions have turned to higher-risk, lower-liquidity strategies, such as private equity.

Muni investors, for their part, are increasingly sensitive to pensions’ widening gap. After the financial crisis and the ensuing recession, they suddenly became interested in pension finances. A report late last year by the Center for Retirement Research at Boston College found that, as pension liabilities grew, spreads between state and local municipal bonds and Treasuries also increased. When such issuers came to issue new debt, they discovered the market was charging them more to borrow. “Pensions have become increasingly relevant to the municipal bond markets and can have a meaningful impact on the borrowing costs of a municipality,” the report says.

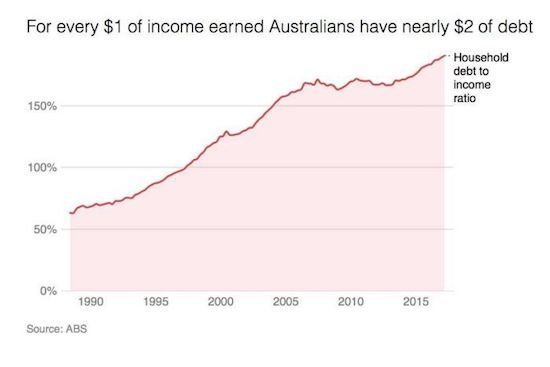

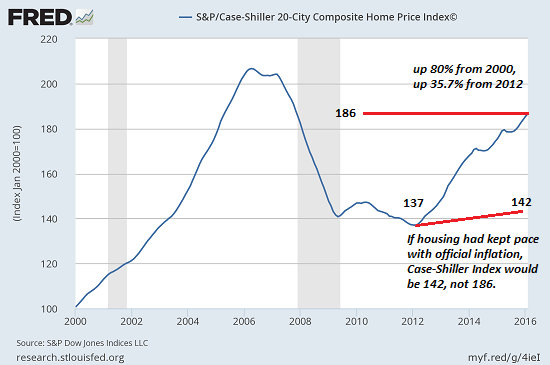

Rising bond yields mean higher mortgage rates. Australia is overflowing with interest only loans. Plenty other countries have loads of it too.

• UK Interest-Only Mortgagees Are at Risk of Losing Their Homes

Some borrowers with interest-only mortgages may lose their homes as a result of shortfalls in repayment plans, the U.K.’s Financial Conduct Authority warned. The FCA has identified three peaks in interest-only mortgage repayments, the first of which is currently underway. Defaults are less likely in the present wave of maturities because the homeowners are approaching retirement and have higher incomes. The next two peaks, from 2027 through 2028 and in 2032, are more at risk of shortfalls, the regulator said. Customers are reluctant to discuss with their lenders how they’ll pay off the loans, limiting their options, the FCA found. Almost 18% of outstanding mortgages in the U.K. are interest-only or involve only partial payment of the capital, according to the statement.

“Since 2013, good progress has been made in reducing the number of people with interest-only mortgages,” Jonathan Davidson, executive director of supervision retail and authorization at the regulator, said in a statement. “However, we are very concerned that a significant number of interest-only customers may not be able to repay the capital at the end of the mortgage and be at risk of losing their homes.” The FCA reviewed 10 lenders representing about 60% of the interest-only mortgage market for the study. The supervisor also urged lenders to review and improve their own strategies regarding repayment of the loans.

Now add some infrastructure.

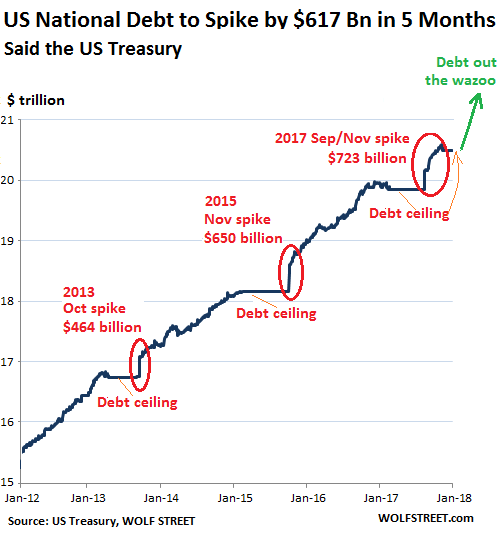

• US National Debt Will Jump by $617 Billion in 5 Months (WS)

While everyone is trying to figure out how to twist the new tax cut to their advantage and save some money, the US Treasury Department just announced how much net new debt it will have to sell to the public through the second quarter to keep the government afloat: $617 billion. That’s what the Treasury Department estimates will be the total amount added to publicly traded Treasury securities — or “net privately-held marketable borrowing” — through the end of the second quarter. This will be the net increase in the US debt through the end of Q2. By quarter: During Q1, the Treasury expects to increase US public debt by $441 billion. It includes estimates for “lower net cash flows.” During Q2 – peak tax seasons when revenues pour into the Treasury – it expects to increase US public debt by $176 billion.

It also “assumes” that with these increases in the debt, it will have a cash balance at the end of June of $360 billion. So over the next five months, if all goes according to plan, the US gross national debt of $24.5 trillion currently – which includes $14.8 trillion in publicly traded Treasury securities and $5.7 trillion in internally held debt – will surge to about $25.1 trillion. That’s a 4% jump in just five months. Note the technical jargon-laced description for this (marked in green on the chart). The flat lines in 2013, 2015, and 2017 are a result of the prior three debt-ceiling fights. Each was followed by an enormous spike when the debt ceiling was lifted or suspended, and when the “extraordinary measures” with which the Treasury keeps the government afloat were reversed. And note the current debt ceiling, the flat line that started in mid-December.

In November, Fitch Ratings said optimistically that, “under a realistic scenario of tax cuts and macro conditions,” the US gross national debt would balloon to 120% of GDP by 2027. The way things are going right now, we won’t have to wait that long. Back in 2012, gross national debt amounted to 95% of GDP. Before the Financial Crisis, it was at 63% of GDP. At the end of 2017, gross national debt was 106% of GDP! Over the next six month, the debt will grow by about 4%. Unless a miracle happens very quickly, the debt will likely grow faster over the next five years due to the tax cuts than over the past five years. But over the past five years, the gross national debt already surged nearly 25%, or by $4.1 trillion. So that’s a lot of borrowing, for an economy that is growing at a decent clip.

Coverage of SOTU proves my point: Moses split the nation.

As for infrastructure, they will go for what provides most short term gain. That is, make people pay. For roads, not public transport, for instance.

• Trump Urges Congress To Pass $1.5 Trillion In Infrastructure Spending (R.)

President Donald Trump called on the U.S. Congress on Tuesday to pass legislation to stimulate at least $1.5 trillion in new infrastructure spending. In his State of the Union speech to Congress, Trump offered no other details of the spending plan, such as how much federal money would go into it, but said it was time to address America’s “crumbling infrastructure.” Rather than increase federal spending massively, Trump said: “Every federal dollar should be leveraged by partnering with state and local governments and, where appropriate, tapping into private-sector investment.” The administration has already released an outline of a plan that would make it easier for states to build tollways and to privatize rest stops along interstate highways.

McKinsey & Company researchers say that $150 billion a year will be required between now and 2030, or about $1.8 trillion in total, to fix all the country’s infrastructure needs. The American Society of Civil Engineers, a lobbying group with an interest in infrastructure spending, puts it at $2 trillion over 10 years. Trump said any infrastructure bill needed to cut the regulation and approval process that he said delayed the building of bridges, highways and other infrastructure. He wants the approval process reduced to two years, “and perhaps even one.” Cutting regulation is a top priority of business lobbying groups with a stake in building projects and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

Just the kind of folk you want in charge of your health. With your medical needs standing in the way of their profits.

• Trump Joins Bezos, Dimon, Buffett In Pledge To Stop Soaring Drug Prices (MW)

President Trump pledged to bring down drug prices. “One of my greatest priorities is to reduce the price of prescription drugs,” Trump said during his State of the Union address on Tuesday evening. “In many other countries, these drugs cost far less than what we pay in the United States and it’s over, very unfair. That is why I have directed my administration to make fixing the injustice of high drug prices one of our top priorities for the year.” Mark Hamrick, Washington, D.C. bureau chief at Bankrate.com, said the president has made that promise before. “Will his choice of a former drug industry executive, Alex Azar, now the head of Health and Human Services, deliver results on that front?” he said. “I’d prefer to place my bet on the partnership just announced by Berkshire Hathaway, J.P. Morgan Chase and Amazon.”

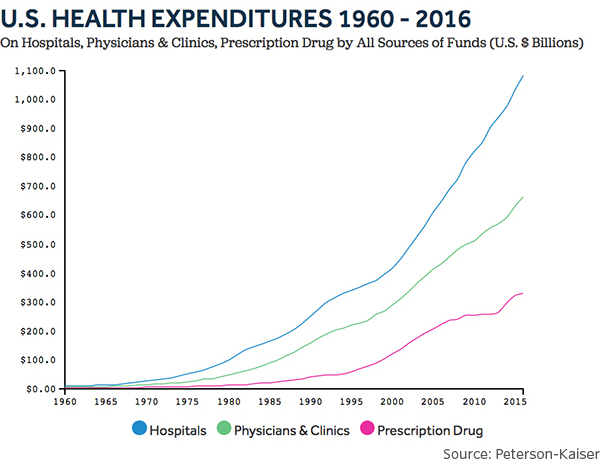

Earlier Tuesday, Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JP Morgan Chase, three of the biggest companies in the U.S., surprised the health-care industry on Tuesday with a plan to form a company to address rising health costs for their U.S. employees. They said it will be “free from profit-making incentives and constraints.” Health-care costs have skyrocketed over the last 60 years, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonprofit, private foundation based in Washington, D.C. In 1960, hospital costs cost $9 billion. In 2016, they cost $1.1 trillion. In 1960, physicians and clinics costs were $2.7 billion, but ballooned to $665 billion. Prescription drug prices soared from $2.7 billion in 1960 to $329 billion. U.S. health-care spending reached $3.3 trillion, or $10,348 per person in 2016.

The Trump administration has pledged to roll back the 2010 Affordable Care Act, perhaps Barack Obama’s signature achievement as U.S. president. Roughly 1 million people will lose their insurance under Trump’s plans, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Berkshire Hathaway chairman and CEO Warren Buffett didn’t hold back in excoriating the health-care industry. “The ballooning costs of health care act as a hungry tapeworm on the American economy,” Buffett said. Amazon founder CEO Jeff Bezos and J.P. Morgan Chase chairman and CEO Jamie Dimon were more measured in their remarks. “Amazon, Chase and Berkshire Hathaway think they can do it better than the insurance companies,” said Jamie Court, president of Consumer Watchdog. “There’s a lot of frustration with the high cost of health insurance, yet government’s offering almost no systemic solutions. It’s as big a change as I have seen in the market in years.”

Just do it?! Perhaps it makes sense not to release it before SOTU, it would have been the only talking point.

• Trump Says ‘100%’ After He’s Asked to Release GOP Memo (BBG)

President Donald Trump was overheard Tuesday night telling a Republican lawmaker that he was “100%” planning to release a controversial, classified GOP memo alleging bias at the FBI and Justice Department. As he departed the House floor after delivering his State of the Union address, C-SPAN cameras captured Representative Jeff Duncan, a South Carolina Republican, asking Trump to “release the memo.” Republican lawmakers say the four-page document raises questions about the validity of the investigation into possible collusion between Trump’s campaign and Russia, now led by Special Counsel Robert Mueller. “Oh yeah, don’t worry, 100%,” Trump replied, waving dismissively. “Can you imagine that? You’d be too angry.”

Republicans in the House moved to release the memo, authored by House Intelligence Chairman Devin Nunes, in a party-line vote on Monday. The move has been opposed by Democrats, who argue the memo gives an inaccurate portrayal of appropriate actions undertaken by law enforcement, and by the Justice Department, which has said it should remain classified. Releasing the memo has become a cause for conservative congressional Republicans, who say the FBI and the Justice Department pursued the investigation of possible Russian ties to the Trump presidential campaign under false pretenses. Trump has as many as five days to review the document for national security concerns, and White House officials insisted earlier Tuesday he hadn’t yet seen the document.

Talk about your American Dream: “..households are living paycheck-to-paycheck even if those paychecks are reasonably large and even if life is comfortable at the moment.”

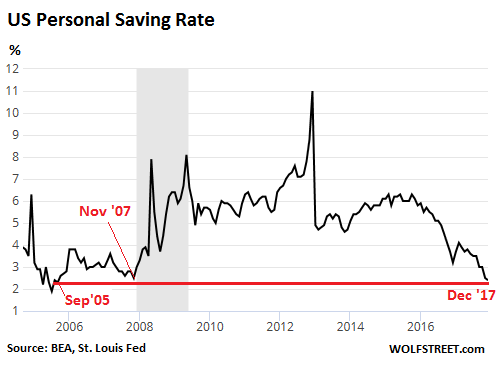

• Saving Rate Drops to 12-Year Low As 50% of Americans Don’t Have Savings (WS)

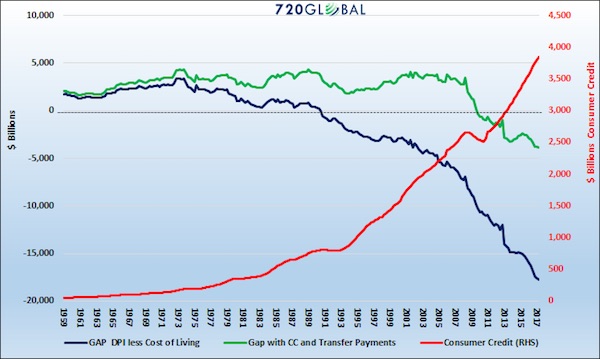

In terms of dollars, personal saving dropped to a Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate of $351.6 billion, meaning that at this rate in December, personal savings for the whole year would amount to $351.6 billion. This is down from the range between $600 billion and $860 billion since the end of the Financial Crisis. But who is – or was – piling up these savings? Numerous surveys provide an answer, with variations only around the margins. For example, the Federal Reserve found in its study of US households: Only 48% of adults have enough savings to cover three months of expenses if they lost their income. An additional 22% could get through the three-month period by using a broader set of resources, including borrowing from friends and selling assets. But 30% would not be able to manage a three-month financial disruption. 44% of adults don’t have enough savings to cover a $400 emergency and would have to borrow or sell something to make ends meet.

Folks who had experienced hardship were more likely to resort to “an alternative financial service” such as a tax refund anticipation loan, pawn shop loan, payday loan, auto title loan, or paycheck advance, which are all very expensive. Similarly, Bankrate found that only 39% of Americans said they’d have enough savings to be able to cover a $1,000 emergency expense. They rest would have to borrow, sell, cut back on spending, or not deal with the emergency expense. All these surveys say the same thing: about half of Americans have little or no savings though many have access to some form of credit, including credit cards, pawn shops, payday lenders, or relatives. So what does it mean when the “saving rate” declines?

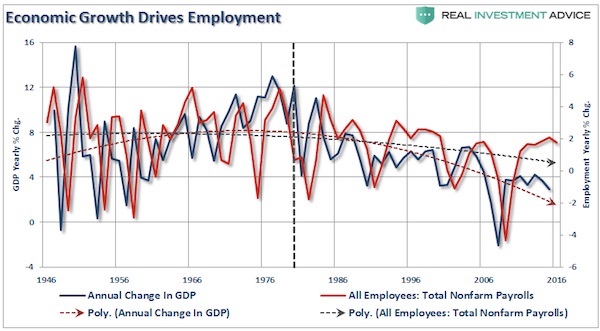

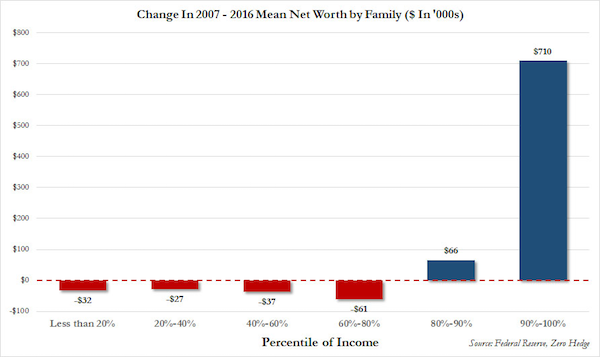

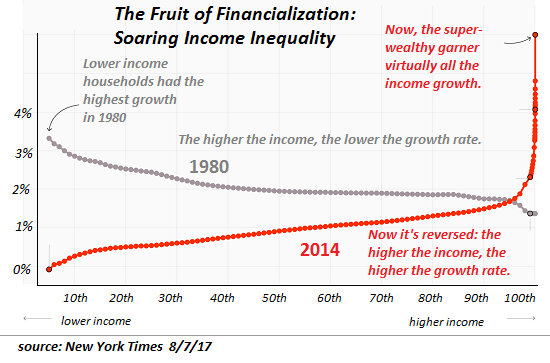

Many households spend more than they make. For them, the personal saving rate is a negative number. This negative personal saving rate translates into borrowing, which explains the 5.7% year-over-year surge in credit card debt, and the 5.5% surge in overall consumer credit. It boils down to this: most of the positive saving rate, with savings actually increasing, takes place at the top echelon of the economy – at the top 40%, if you will – where households are flush with cash and assets and where the saving rate is very large. But the growth in borrowing for consumption items (the negative saving rate) takes place mostly at the bottom 60%, where households are living paycheck-to-paycheck even if those paychecks are reasonably large and even if life is comfortable at the moment.

Peculiar: $2.3 billion ‘worth’ of a dollar-pegged ‘currency’, backed by nothing much in proof.

• U.S. Regulators Subpoena Crypto Exchange Bitfinex, Tether (BBG)

U.S. regulators are scrutinizing one of the world’s largest cryptocurrency exchanges as questions mount over a digital token linked to its backers. The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission sent subpoenas on Dec. 6 to virtual-currency venue Bitfinex and Tether, a company that issues a widely traded coin and claims it’s pegged to the dollar, according to a person familiar with the matter, who asked not to be identified discussing private information. The firms share the same chief executive officer. Tether’s coins have become a popular substitute for dollars on cryptocurrency exchanges worldwide, with about $2.3 billion of the tokens outstanding as of Tuesday.

While Tether has said all of its coins are backed by U.S. dollars held in reserve, the company has yet to provide conclusive evidence of its holdings to the public or have its accounts audited. Skeptics have questioned whether the money is really there. “We routinely receive legal process from law enforcement agents and regulators conducting investigations,” Bitfinex and Tether said Tuesday in an emailed statement. “It is our policy not to comment on any such requests.” Bitcoin, the biggest cryptocurrency by market value, tumbled 10% on Tuesday. It fell another 3.2% to $9,766.41 as of 9:19 a.m. in Hong Kong, according to composite pricing on Bloomberg. The virtual currency hasn’t closed below $10,000 since November.

Who’s aiding Spain in keeping its problems hidden? 30,000 complaints in 9 months, and the ECB is silent?!

• Customer Lawsuits Pummel Spanish Banks (DQ)

Following a succession of consumer-friendly rulings, bank customers in Spain are increasingly taking their banks to court. And many of them are winning. Last year an unprecedented wave of litigation against banks forced the Ministry of Justice to set up dozens of courts specialized in mortgage matters to prevent the collapse of the rest of the national judicial system. The Bank of Spain, according to its own figures, received 29,957 complaints from financial consumers between January and September 2017 — already double that of the previous year and by far the highest number of complaints registered since 2013, a record year when investors and customers were desperately trying to claw back the money they’d lost in the preferred shares that issuing banks had pushed on their own customers as savings products.

In 2017, eight out of 10 complaints related to one key product: mortgages, and in particular the so-called “floor clauses” contained within them. These floor clauses set a minimum interest rate — typically of between 3% and 4.5% — for variable-rate mortgages, even if the Euribor dropped far below that figure. This, in and of itself, was not illegal. The problem is that most banks failed to properly inform their customers that the mortgage contract included such a clause. Those that did, often told their customers that the clause was an extreme precautionary measure and would almost certainly never be activated. After all, they argued, what are the chances of the Euribor ever dropping below 3.5% for any length of time? At the time (early 2009), Europe’s benchmark rate was hovering around the 5% mark.

Within a year it had crashed below 1% and has been languishing at or below zero ever since. As a result, most Spanish banks were able to enjoy all the benefits of virtually free money while avoiding one of the biggest drawbacks: having to offer customers dirt-cheap interest rates on their variable-rate mortgages. But all that came to a crashing halt in May 2013 when Spain’s Supreme Court ruled that the floor clauses were abusive and that the banks must reimburse all the funds they’d overcharged their mortgage customers — but only from the date of the ruling! Then, on December 21, 2016, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) delivered a further hammer blow when it acknowledged the right of homeowners affected by “floor clauses” to be reimbursed money dating back to when the mortgage contract was first signed. Since the ECJ ruling, law firms are now so confident of winning floor-clause cases that they’re even offering no win, no-fee deals.

US and UK suffer from the exact same problem.

• Britons Ever More Deeply Divided Over Brexit (R.)

The social divide revealed by Britain’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union is not only here to stay but deepening, according to academic research published on Wednesday. Think tank The UK in a Changing Europe said Britons were unlikely to change their minds about leaving the EU, despite the political and economic uncertainty it has brought, because attitudes are becoming more entrenched. “The (Brexit) referendum highlighted fundamental divisions in British society and superimposed a leave-remain distinction over them. This has the potential to profoundly disrupt our politics in the years to come,” said Anand Menon, the think tank’s director.

Britain is negotiating a deal with the EU which will shape future trade relations, breaking with the bloc after four decades, but the process is complicated by the divisions within parties, society and the government itself. Menon said the research, based on a series of polls over the 18-month period since Britain voted to leave the European Union, showed 35% of people self-identify as “Leavers” and 40% as “Remainers”. Research also found that both sides had a tendency to interpret and recall information in a way that confirmed their pre-existing beliefs which also added to the deepening of the impact of the vote. The differences showed fragmentation was more determined by age groups and location than by economic class.

Polls have shown increasing support for a second vote on whether or not to leave the European Union once the terms of departure are known, but such a vote would not necessarily provide a different result, a poll by ICM for the Guardian newspaper indicated last week. The report also showed that age was a better pointer to how Britons voted than employment. Around 73% of 18 to 24-year-olds voted to stay in the EU, but turnout among that group was lower than among older voters. “British Election Study surveys have suggested that, in order to have overturned the result, a startling 97% of under-45s would have had to make it to the ballot box, as opposed to the 65% who actually voted,” the report said.

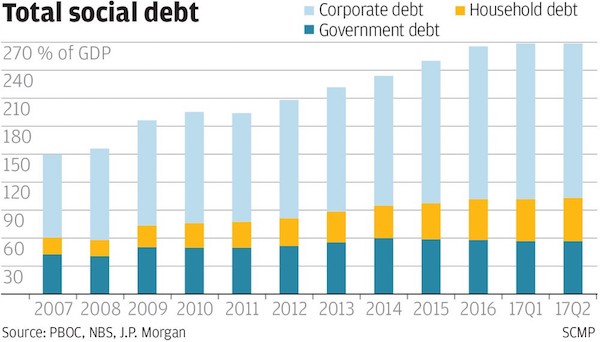

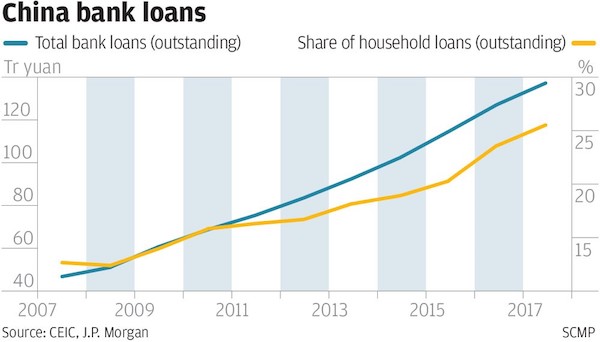

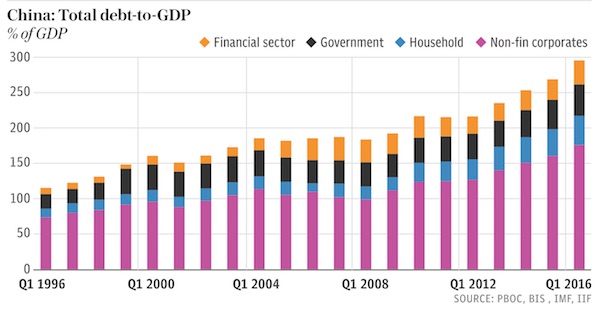

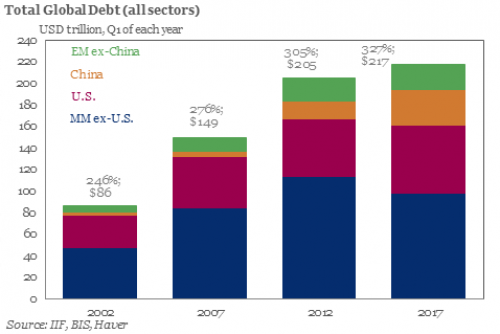

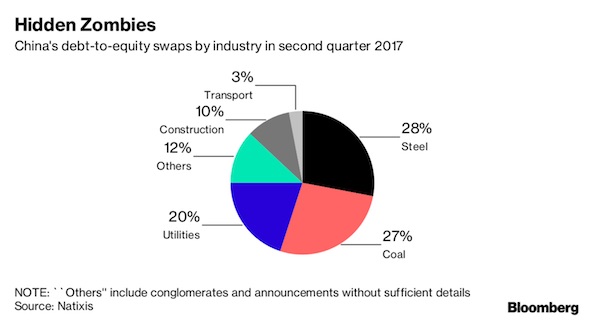

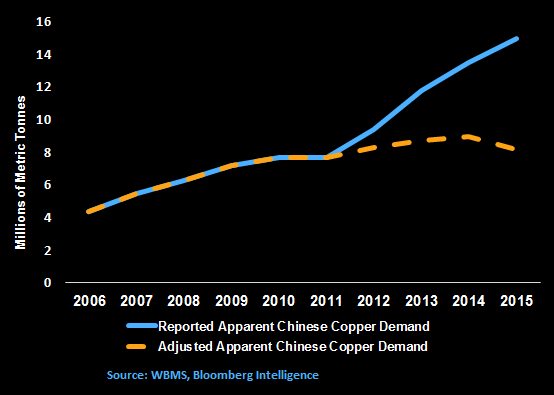

How China hides debt through swaps. As US and EU have done for ages now.

• The GDP of Bridges to Nowhere (Michael Pettis)

In most economies, GDP growth is a measure of economic output generated by the performance of the underlying economy. In China, however, Beijing sets annual GDP growth targets it expects to meet. Turning GDP growth into an economic input, rather than an output, radically changes its meaning and interpretation. On January 18, 2018, China’s National Bureau of Statistics announced that the country’s GDP grew by 6.9% in 2017. A day earlier, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) announced that total social financing (TSF) in 2017 had increased to 19.44 trillion renminbi.

[..] I was recently part of a discussion on a listserv that brings together Chinese and foreign experts to exchange views on China-related topics. What set off this discussion was a claim that the Chinese economy began to take deleveraging seriously in 2017. Everyone agreed that debt in China is still growing far too quickly relative to the country’s debt-servicing capacity, but the pace of credit growth seems to have declined in 2017, even as real GDP growth held steady and, more importantly, nominal GDP growth increased. I was far more skeptical than some others about how to interpret this data. It is not just the quality of data collection that worries me, but, more importantly, the prevalence in China of systemic biases in the way the data is collected. Not all debt is included in TSF figures. The table above, for example, indicates a fall in TSF in 2015, but this did not occur because China’s outstanding credit declined.

[..] in 2015 there was a series of debt transactions (mainly provincial bond swaps aimed at reducing debt-servicing costs and extending maturities) that extinguished debt that had been included in the TSF category and replaced it with debt not included in TSF. The numbers are large. According to the China Daily, there were 3.2 trillion renminbi worth of bond swaps in 2015, plus an additional 600 billion renminbi of new bonds issued. If we adjust TSF by adding these back, rather than indicate a decline of 6.4%, we would have recorded an increase of 15.7%. [..] The point is that the deceleration in credit growth implied by TSF data might indeed reflect the beginning of Chinese deleveraging, but it could also reflect the surge in regulatory concern. In the latter case, this would mean that China has experienced not the beginnings of deleveraging, but rather a continuation of the trans-leveraging observers have seen before.