Edwin Rosskam Shoeshine, 47th Street, Chicago’s main Negro business street 1941

First off, no, I don’t think Syriza is a problem, I just couldn’t resist the Sound of Music link once it popped into my head, as in ‘headlines you can sing’. I think Syriza may well be a solution, if it plays its cards right. But that still leaves politicians and investors denominating Tsipras et al as a problem, if not a menace. Now, investors may not need to possess any moral values – though things would probably have been much better if that were a requirement -, but you can’t say the same for politicians. Politics is supposed to BE about moral values.

And supporting Samaras and his technocrat oligarchy, as has been the EU/Troika policy, doesn’t exactly show a high moral standard. Not just because trying to influence an election is an no-go aberration (though it’s so common in the EU you’d almost forget that), but certainly also because of what Samaras and the EU have done to the Greek people over the past few years. And neither does it show in what happens now, where the Greeks, steeped in Troika-induced misery as they are, are labeled greedy bastard cheats.

Since the EU lies as much about Greece as it does about Russia, it’s only fitting that the former should speak out for the latter. And it’s deliciously easy: the EU wants to step up sanctions against Russia (because the Ukraine shelled Mariupol?!), but EU sanctions decisions require unanimity. Since Greek-Russian relations have historically been close, Syriza resisting ever tighter sanctions should be no surprise.

At the end of the day, European taxpayers shouldn’t be angry at Greece, no matter how much their media try to stoke that anger, but at their own banks, governments and central banks. Things pertaining to Greece and its debt are not at all what they seem. Most of it is just another narrative originating in Brussels, Frankfurt and the financial media cabal. Not much is left of this narrative if we dig a little deeper. This from Mehreen Khan for the Telegraph today may be a little ambivalent in what it points to, but it certainly puts the Greek debt in a different light from the ‘official’ one:

Three Myths About Greece’s Enormous Debt Mountain

€317bn. Over 175% of national output. That’s the enormous debt mountain that faces the new Greek government. It is the issue over which the country is set to clash with other countries in the eurozone. As it stands, Greece’s debt-to-GDP ratio is the highest in the currency bloc. It has been steadily rising as the country has undergone painful austerity and experienced a severe contraction in economic output. The new far-left/right-wing coalition is now demanding a write-off of up to 50% of its liabilities. The government argues that this is the only way Greece can remain in the single currency and prosper.

According to the newly appointed finance minister, who first coined the term “fiscal waterboarding” to describe Greece’s plight, the EU has loaded “the largest loan in human history on the weakest of shoulders – the Greek taxpayer”. So far, the rest of the eurozone is adamant that it will not meet demands for debt forgiveness. And yet, the value of Greece’s debt mountain has been called a meaningless “accounting fiction” by Nobel laureate Paul Krugman. So what does Greece’s €317bn debt really mean for the country and its creditors? And can it ever be paid back?

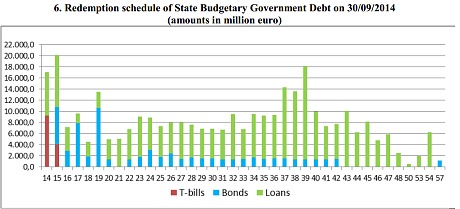

Myth 1: They can never pay it back. Ever. Never say never. On the issue of repaying back its liabilities, it’s more a question of time, rather than money. Greece has already been the beneficiary of a number of debt extensions, and in 2012, underwent the biggest private sector debt restructuring in history. The average maturity on Greek government debt currently stands at 16.5 years. The sustainability, or otherwise, of the country’s burden relies more on the timetable for repayment rather than the overall stock of the debt, argue many economists. The chart below shows the repayment schedule on the country’s €245bn rescue package and extends all the way out to 2054.

Source: Hellenic Republic Public Debt Bulletin

Although the question of cancelling any portion of the principal owed to Greece’s creditors seems to be a firm no-go area, the idea of further debt extensions could be an option. But as noted by Ben Wright, allowing Greece more time to payback its loans is still a fiscal transfer in all but name.

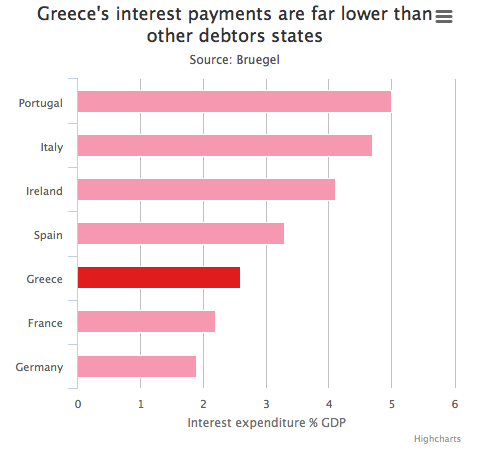

Myth 2: Greece is paying punitive interest rates. Not really. Greece has managed to negotiate favourable terms on which it can service the cost of its loans and the interest paid by the country is far below that of Spain, Ireland, and Portugal (see chart below). Think-tank Bruegel calculates that Greece paid a sum equal to around 2.6% of its GDP (rather than the widely quoted figure of around 4%) to service its loans last year. This is because Greece will actually receive back the interest it pays to the ECB should it continue to meet its bail-out conditions.

Even without a further renegotiation on interest payments, the costs could be even lower this year. In the words of economist Zolst Darvas from Bruegel:

Given that interest rates have fallen significantly from 2014, actual interest expenditures of Greece will be likely below 2% of GDP in 2015, if Greece will meet the conditions of the bail-out programme.

It is this combination of such long maturities and rock-bottom interest rates, that has led at least one former ECB governing board member to argue that Greece’s debt burden is far more sustainable than many of its southern neighbours.

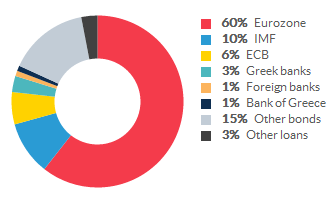

Who owns Greek debt? (Source: Open Europe)

Myth 3: Greece won’t recover without debt forgiveness. Wrong again. For all the fixation on the outstanding stock of Greek debt, kickstarting growth in the country is more likely to happen through a relaxation of budget rules rather than a debt cancellation. With the coffers looking sparse, the Syriza-led government is also asking for a renegotiation of the surplus rules imposed on the country. Greece is currently required to run a primary surplus of 4.5% of its GDP. Before taking account of its debt interest payments, it is likely to achieve a primary budget surplus of around 3% of its national output this year. This severely limits the new government’s room for fiscal manoeuvre. It also makes it almost impossible for Syriza to fulfil its pre-election promises to raise the minimum wage and create public sector jobs.

According to calculations from Paul Krugman:

Dropping the requirement that Greece run a primary surplus of 4.5% of GDP would allow spending to rise by 9% of GDP, and that this would raise GDP by 12% relative to what it would have been otherwise. Unemployment would fall by around 10% relative to no relief.

None of this is to deny that Greece would hugely benefit from a significant debt cancellation. But the politics of the eurozone means that this is virtually impossible. However, there do seem to be other ways that Greece could start tackling its enormous debt mountain.

And if that is not enough to change your mind about what the reality is in the Greek debt situation, David Weidner at MarketWatch has more, from an entirely different angle, that nevertheless hammers the official narrative just as much, if not more. Weidner refers to work by French economist Eric Dor, as cited by Mish Shedlock last week. What Dor contends is that a very substantial part of Greece’s debt to EU taxpayers was nothing but Wall Street wagers gone awry.

Not exactly something one can blame the Greeks in the street for, just perhaps the elite and oligarchy. Instead of restructuring their banks, the richer nations of Europe, like the US, decided to transfer their gambling losses to the people’s coffers. And though there are all kinds of reasons provided, which even Weidner suggests may be ‘genuine’, not to restructure a banking system, in the end it is a political choice made by those who owe their power to those same banks.

The result has been that Greece was saddled with so much debt, they had to borrow even more, and the Troika could come in and unleash a modern day chapter of the Shock Doctrine. How convenient.

How Wall Street Squeezed Greece – And Germany

Europe’s political leaders and bankers would have you believe that the conflict between Greece and the European Union is a tug of war between a deadbeat nation and its richer ones who have come to the debtor’s aid time and time again. Instead, what most of these leaders miss is that it’s a bank bailout in plain view.

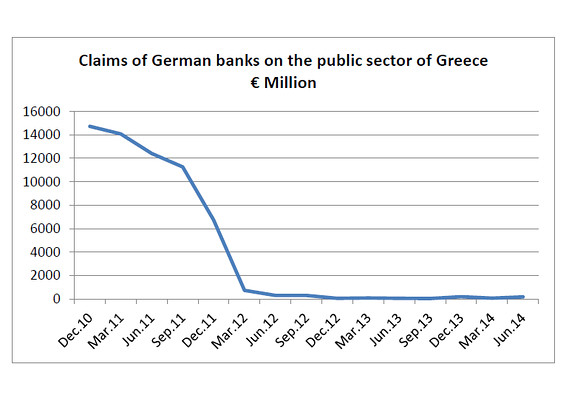

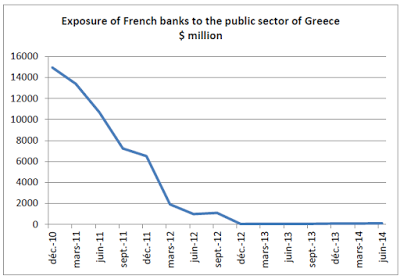

What’s really happened is that since Greece ran into serious trouble repaying its debts four years ago, Germany, France and the EU have instituted what can only be described as a massive bailout of its own financial system – shifting the burden from banks to taxpayers. Last week, Mike Shedlock republished research by Eric Dor, a French business school director, and it shows the magnitude of the shift. To put it simply, German taxpayers are on the hook for roughly $40 billion in Greek debt. German banks? Just $181 million, though they do hold $5.9 billion in exposure to Greek banks. Those numbers are a flip-flop from where things stood less than five years ago.

German banks were heavily exposed to Greek debt when the crisis began, but they’ve been bailed out and now German taxpayers are on the hook. French banks were similarly bailed out by the European Union.

This massive shift from private gains to public losses was done through the European Financial Stability Facility. Created in 2010, this was the European Union’s answer to the U.S. Troubled Asset Relief Program, the Treasury Department’s 2008 bailout program. There are some differences. The EFSF issues bonds, for instance, but the principle is the same. Governments buy bad bank debt and hold it on the public’s books.

The terms set by the EFSF are basically what’s at issue when we hear about Greece’s new government being opposed to austerity in their nation. The Syriza victory, which was a sharp rebuke to the massive cost-cutting in government spending, including pensions and social welfare costs, drew warnings from leaders across Europe. “Mr. Tsipras must pay, those are the rules of the game, there is no room for unilateral behavior in Europe, that doesn’t rule out a rescheduling of the debt,” ECB’s Benoît Coeuré said.

“If he doesn’t pay, it’s a default and it’s a violation of the European rules.” British Prime Minister David Cameron’s Twitter account said, the Greek election results “will increase economic uncertainty across Europe.” And Jens Weidmann, president of the German central bank, warned the new ruling party that it “should not make promises that the country cannot afford.” Those sound like very threatening words. And one wonders if these same officials made the same tough statements to Deutsche Bank, Commerzbank, Credit Agricole or SocGen when they were faced with potentially billions in losses when the banks were holding Greek debt.

European leaders such as Angela Merkel in Germany, Francois Hollande in France and Finnish Prime Minister Alexander Stubb have been eager to beat down Greece and stir broader support at home by making it an us-against-them game. Not to deny that Greece’s financial troubles do threaten the European Union, but today’s crisis pitting nation against nation was created by these leaders in an effort to minimize losses at their biggest lending institutions. Perhaps the move to shift Greek liabilities to state-owned banks (Germany’s export/import bank holds $17 billion in Greek debt) was necessary, but that doesn’t make it fair, or the right thing to do. Europe, like the United States, seems to be at the beck and call of its financial industry.

Michael Hudson recognized this early on. In 2011 he wrote that in Europe there is a belief “governments should run their economies on behalf of banks and bondholders. “They should bail out at least the senior creditors of banks that fail (that is, the big institutional investors and gamblers) and pay these debts and public debts by selling off enterprises, shifting the tax burden onto labor. To balance their budgets they are to cut back spending programs, lower public employment and wages, and charge more for public services, from medical care to education.”

Yes, Greece overspent. But to do so, someone had to overlend. German and French banks did so because of an implicit guarantee by the EU that all nations would stick together. Well, the bankers and politicians have stuck together. Everyone else seems to be on their own. Merkel and the austerity hawks of Europe who won’t share the responsibility for a system’s failure are doing the bidding of banks. At least in Greece, the lawmakers are put into power by the people.

And that still leaves unaddressed that Greece as a whole may have overspent and -borrowed, but it was the elite that was responsible for this, egged on by the likes of Goldman Sachs, whose involvement in the creative accounting that got Greece accepted into the EU, as well as the derivatives that are weighing down the nation as we speak, is notorious.

The world’s major banks got rich off the back of the Greek population at large, and when their wagers got so absurd they collapsed, the banks saw to it that their losses were transferred to European -and American – taxpayers. And those taxpayers are now told to vent their anger at those cheating, lazy Greeks, who are actually notoriously hard workers, who have doctors prostituting themselves, and many of whom have no access to the health care those same doctors should be providing, and whose young people have no future to speak of in their own magnificently beautiful nation.

The Troika, the EU, the IMF, and the banks whose sock puppets they have chosen to be, are a predatory force that has come a long way towards wiping Greece off the map. And we, whether we’re European or American, are complicit in that. It’s Merkel and Cameron etc., who have allowed for their banks to transfer their casino losses to the – empty – pockets of the Greeks, and of all of us. That is the problem here.

And that’s what Syriza has set out to remediate. And for that, they deserve, and probably will need, our unmitigated support. It’s not the Greek grandmas (they’re dying because they have no access to a doctor) who made out like bandits here. It’s the usual suspects, bankers and politicians. And you and I, too, are eerily close to being the usual suspects. We should do better. Or else we are dead certain of being next in line.